By now, we’ve all seen the sobering statistics illustrating just how out-of-shape and unhealthy America’s youth have become. About one in three elementary school students is overweight or obese (Ogden et al., 2014), the prevalence of obesity increased almost threefold among children 6 to 11 years old between 1980 and 2010 (Ogden et al., 2014) and, during that same 30-year window, children’s muscular fitness and fundamental motor skills declined significantly (Cohen et al., 2011; Runhaar et al., 2010). Worse yet, these trends appear to be associated with cardiometabolic biomarkers in unfit youth, including elevated blood pressure and insulin resistance (Gutin and Owens, 2011).

Among the many potential causes of the childhood obesity epidemic, which range from commercials for sugary cereals during early-morning cartoons to dramatic increases in screen time, is one that should be of interest to any health and fitness professional: the ongoing reduction in physical education during the school day, and the associated downward trend in overall physical activity among the nation’s youth. Only 30 to 42 percent of children ages 6 to 11 perform the recommended 60 minutes of large-muscle movement most days of the week (Sisson and Katmarzyk, 2008; Troiano et al., 2008; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1996).

So what can we as an industry to do help? To learn more, ACE enlisted the help of Wayne Westcott, Ph.D., and a team of researchers at Quincy College in Quincy, Mass., who evaluated a school-based physical-activity program called Build Our Kids’ Success (BOKS), which has been implemented in more 1,200 schools worldwide. The BOKS program is run by volunteer instructors and provides 50-minute sessions of large-muscle activity before school three days each week. ACE's goal was to determine if BOKS is a safe and effective program that health and fitness professionals should consider becoming involved with, and if it is a program that can serve as a model for other youth-fitness initiatives.

The research team evaluated the effects of the BOKS program on various elements of children’s health and fitness:

- Body weight

- Percent body fat

- Fat weight

- Lean weight

- Muscle strength

- Joint flexibility

- Aerobic performance

The Study

To conduct the study, which was published earlier this year in the Journal of Exercise, Sports & Orthopedics, Dr. Westcott and his team chose two public schools, one of which offered the BOKS program and one of which did not. The latter school served as the control group. Both groups of students, from kindergarten through fourth grade, participated in their usual physical-education programs during the school day throughout the duration of the study.

Physical assessments were conducted at both schools before and after a nine-week period, during which the BOKS participants completed three 50-minute sessions each week. The sessions were conducted by a lead instructor who had been running the program for more than a year, along with a team of parent volunteers that had completed training courses to become “certified BOKS exercise instructors.” The program used BOKS-approved lesson plans that involved a variety of continuous and intermittent physical activities, including group games, running relays, locomotor movements, body-weight exercises and controlled stretches. Dr. Westcott notes that the kids were always active, but in a controlled manner, and most of the activities were fun and teamwork-oriented.

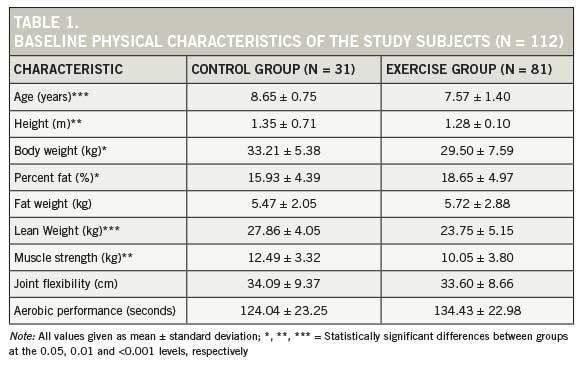

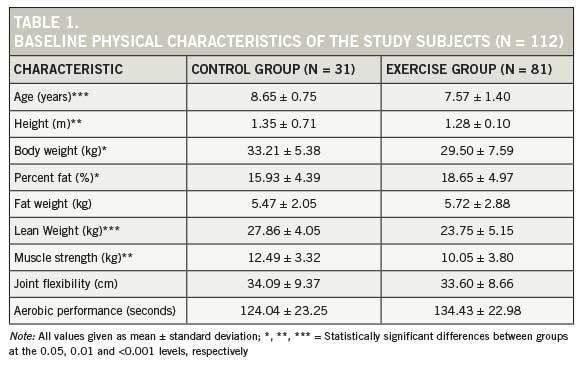

For the study, 81 students made up the exercise group, while 31 students made up the control group. The researchers simply assessed the selected physical characteristics for the two groups and had no involvement with the actual BOKS program. The baseline physical characteristics for the 112 study participants are presented in Table 1.

The Results

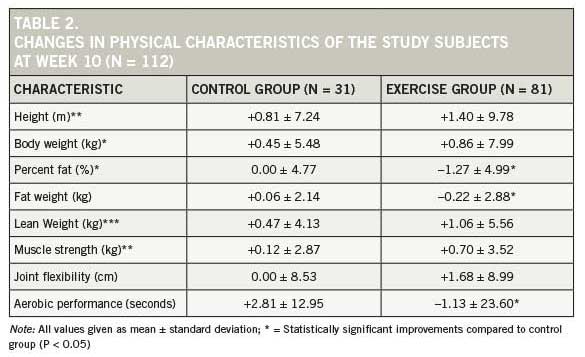

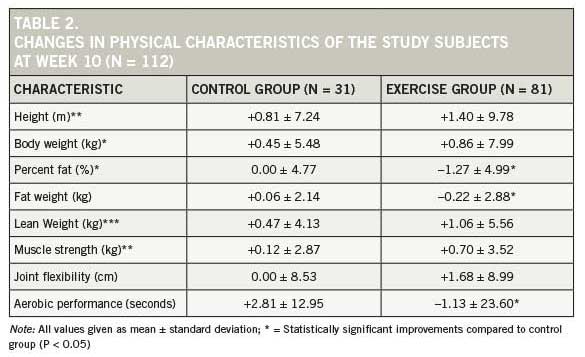

Table 2 summarizes the changes in physical characteristics of kids after the nine-week program.

As demonstrated in Table 2, there were statistically significant improvements among the exercise group in three characteristics: percent fat, fat weight and aerobic performance. Conspicuously absent from this list is body weight. Before delving into that, let’s look at each of the three areas where improvements were measured.

Percent body fat: The exercise group experienced a mean 1.27 percent reduction in percent body fat, while the control group saw no change at all.

Fat weight: Here, the control group gained a mean 0.06 kg of fat weight, while the exercise group lost 0.22 kg of fat.

Aerobic performance: To measure this aspect of fitness, researchers had the kids complete a 400-meter run. The kids in the control group actually slowed down by a mean of 2.81 seconds over the course of the study, while the exercise group improved their time by a mean of 1.13 seconds.

But what about body weight? The kids in the control group gained a mean of 0.45 kg, while those in the exercise group gained 0.86 kg. Statistical analysis determined that this was not a significant difference, but digging a bit deeper reveals that when you couple the weight gained by the BOKS kids with the decrease in fat weight they experienced, you find an important and positive impact on the participants’ body composition. This is yet another piece of evidence that using the bathroom scale to measure successes and failures is never a good idea.

The Bottom Line

While the research team did feel that the children in the BOKS program could benefit from the performance of more resistance exercise and perhaps some static stretching, Dr. Westcott is very quick to point out that BOKS is, overall, a great program. “It’s a great success,” he says. “Teachers, parents and kids love it, so I’d be hesitant to change a thing. You don’t want to lose that excitement for physical activity.” In fact, it appears that the BOKS program is one that health and fitness professionals should consider emulating in their efforts to combat the global obesity epidemic among children.

References

Cohen, D. et al. (2011). Ten-year secular changes in muscular fitness in English children. Acta Paediatrica, 100:e175-7. DOI: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02318.x.

Gutin, B. & Owens, S. (2011). The influence of physical activity on cardiometabolic biomarkers in youths: A review. Pediatric Exercise Science, 23, 2, 169–185.

Ogden, C.L. et al. (2014). Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. Journal of the American Medical Association, 311, 8, 806–814. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2014.732.

Runhaar, J. et al. (2010). Motor fitness in Dutch youth: Differences over a 26- year period (1980–2006). Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 13, 3, 323–328. DOI: 10.1016/j.jsams.2009.04.006.

Sisson, S.B. & Katzmarzyk, P.T. (2008). International prevalence of physical activity in youth and adults. Obesity Reviews, 9, 6, 606–614. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00506.x.

Troiano, R.P. et al. (2008). Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 40, 1, 181–188.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (1996). Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Ga.: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.