An estimated 1 million Americans are living with Parkinson’s disease, according to data from the American Parkinson Disease Association, and that number is expected to double by 2030. Parkinson’s, which is the second most common neurodegenerative disease following Alzheimer’s disease, is a type of movement disorder that can affect the ability to perform common, daily activities. It is chronic, progressive and most likely to be diagnosed in older adults.

You’re likely familiar with the external signs of Parkinson’s, particularly the resting tremors. Other symptoms include bradykinesia (slowness of movement), postural instability and rigidity. Doctors typically prescribe medications such as Levodopa to help control the symptoms of the disease, particularly the slow movements and muscle rigidity. Not surprisingly, both the symptoms of Parkinson’s and the prescribed medications can affect the normal response to exercise. Taken together, these facts and factors, make it essential that you are aware of the unique modifications to the exercise programming needs of this underserved and vulnerable segment of our population.

This article, which features 10 key programming considerations I have gleaned from working with this clientele, is intended as a guide for health and exercise professionals who currently or may one day work with clients who have Parkinson’s disease.

10 Key Programming Considerations for Clients With Parkinson’s Disease

1. Understand how common medications given to treat symptoms of Parkinson’s disease may influence an individual’s exercise response.

It is uncommon for individuals who are younger than 50 years to be diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. However, the incidence increases 5- to 10-fold after the age of 60. In this age demographic, millions of Americans take a wide range of prescribed medications to manage various chronic conditions, such as high cholesterol, hypertension, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD). Therefore, it is critical that you understand how certain medications influence the exercise response.

Five commonly prescribed medications are beta blockers, ACE inhibitors, diuretics, antihyperlipidemics and antidiabetics, with the percentage of American adults taking these medications increasing at age 65 and older. Here are just a few of the ways these drugs might impact the exercise response:

- Beta blockers elicit lower heart rate and blood pressure responses to a given exercise workload.

- Individuals on ACE inhibitors and diuretics have both lower resting and exercise blood pressure values.

- Individuals taking both ACE inhibitors and diuretics may experience a reduction in blood pressure from both these categories of medications. When combined with a natural-occurring postexercise hypotension, an excessive reduction in blood pressure may occur.

- For individual’s taking statins, it is advised to take caution with intense exercise due to the association between the drug and exertional rhabdomyolysis.

- Oral hypoglycemics influence the transport of glucose from the blood into skeletal muscle and can increase the potential risk for exercise-induced hypoglycemia.

2. Individuals with Parkinson’s disease are likely to be older adults who also have comorbidities.

Older adults are defined as men and women 65 years or older and adults aged 50 to 64 years who have clinically significant chronic conditions and/or functional limitations that impact movement ability, fitness or physical activity. Despite these age ranges, don’t assume that chronological age equates to physiological or functional age. Indeed, people of similar ages can differ remarkably in functional capacity, which in turn will affect how they respond to exercise and training recovery. Although it is inevitable that physiological function will decline with age, the rate and magnitude of change is dependent on a complex interaction of genetics, individual health and exercise training/physical activity status. Safe and effective training recovery programming for older adults requires you to understand the effects of aging on physiological function.

Approximately 80% of individuals aged 65 years or older are living with at least one chronic health problem, and 68% are living with two chronic conditions. Here are several programming considerations to keep in mind when training older clients who have comorbidities:

- With permission, ask your client’s medical team about any specific limitations to be aware of when designing their exercise program (including specific exercises to avoid).

- One strategy to employ when working with clients with comorbidities is to design the overall exercise program around the condition that poses the greatest risk of mortality for the individual.

- Individuals with multiple comorbidities may possess conditions, such as low-back pain, osteoarthritis or fibromyalgia, that fluctuate significantly from day to day in terms of severity. For this reason, it’s important to be prepared to accommodate an ever-changing chronic condition landscape with these types of clients and constantly adjust the session to best serve the client on any given day.

Clients who have Parkinson’s disease are generally older clients with comorbidities.

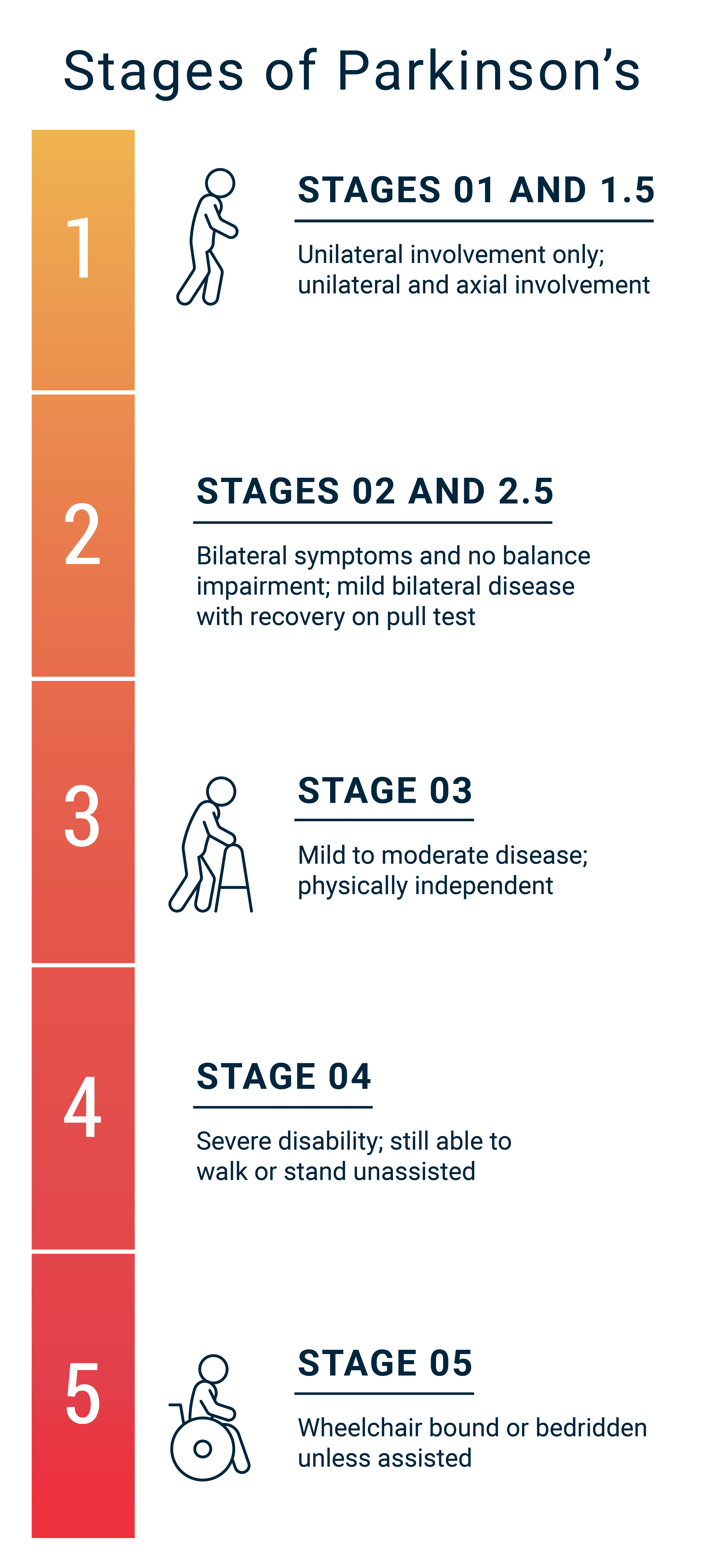

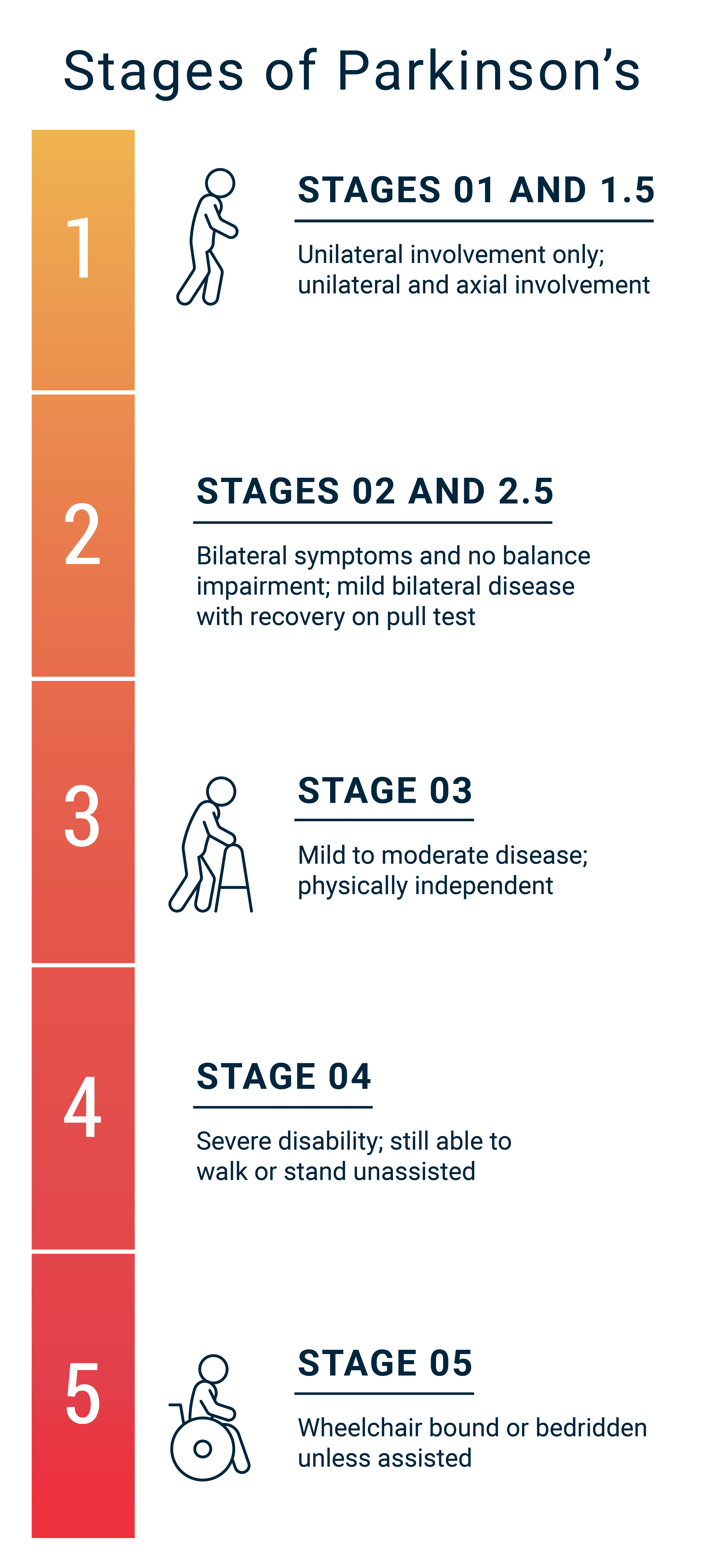

3. Familiarize yourself with the stages of Parkinson’s disease severity.

The progression of the stages of Parkinson’s disease are outlined by the Hoehn and Yahr scale (Figure 1). While individuals in the first two stages of Parkinson’s do not exhibit symptoms of postural instability, overall symptoms and functional limitations worsen as individuals progress to stages 3 and 4. As health and exercise professionals, it important to collaborate with your clients and their medical providers to understand the stage of Parkinson’s’ disease severity. This can provide important insight into the degree of supervision required, as well as guide the design and implementation of safe and effective exercise programming.

Figure 1.

4. Assessments are essential for safe and effective exercise programming.

When working with clients, you perform assessments for a number of important reasons, including to establish baseline values and guide exercise programming. Additionally, assessments are valuable to establish training goals and guide program progressions. As noted earlier, clients with Parkinson’s disease are generally older and possess comorbidities. They’re also likely to engage in low levels of physical activity. For this reason, assessing cardiovascular risk factors is important. Autonomic dysfunction is a hallmark feature of Parkinson’s disease, especially as the disease progresses. Assessing heart rate and blood pressure at rest, along with postural changes and exercise tolerance, is important to determine safe and effective programming.

5. Be sure to complete assessments in the proper order.

The order of assessments is critical for Parkinson’s disease clients due to the likely presence of postural instability, which refers to impairments in balance that compromise the ability maintain or change posture in activities such as standing and walking. Assessments for postural instability should be performed first within any battery of assessments after gathering any necessary resting measurements (e.g., heart rate, blood pressure and body composition). Possible options include the Berg Balance Scale, Timed Up and Go test and chair sit-to-stand test. The results from these assessments can help guide your decision-making on whether it’s safe to have individual clients perform additional assessments for cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness.

6. Prioritize adherence and maintenance as key program outcomes.

You can employ numerous strategies to enhance exercise adherence among your clients, including identifying individualized, attainable goals and objectives for exercise. Longitudinal data suggests that older adults and those with chronic diseases who engage in regular exercise exhibit a healthier profile when compared to individuals who don’t exercise regularly. To encourage adherence, programs for older adults with Parkinson’s disease should aim to encourage the types of activities they enjoy doing, such as walking in groups, resistance training focused on functionality of movement, aquatic exercise, yoga, Tai Chi and balance exercises.

Additionally, understanding the natural progression of Parkinson’s disease can help you establish realistic program goals for clientele. Rather than unrealistically expect improvements in numerous health benefits, acknowledge the reality of the disease and focus on maintenance and delayed Parkinson’s progression as triumphant outcomes.

7. Follow the ACE Integrated Fitness Training® (ACE IFT®) Model guidelines when designing clients’ cardiorespiratory and muscular training programs, but be aware of specific programming considerations.

In general, health and exercise professionals can use the ACE IFT Model guidelines for cardiorespiratory and muscular training with clients who have Parkinson’s disease. However, keep in mind the following considerations:

- As mentioned previously, clients with Parkinson’s disease can suffer from autonomic dysfunction, which can impact balance and overall well-being. Medications used to treat the disease, such as Levodopa and Carbidopa, can worsen autonomic dysfunction. Be particularly cautious or avoid exercise when a client has had a recent change in medication, as blood pressure and heart rate responses maybe unknown.

- Unfortunately, Parkinson’s disease is often accompanied by a decline in cognitive function or dementia. Be mindful of these challenges when designing exercise programs to ensure safety and request additional supervision if needed.

- Clients with Parkinson’s disease may experience freezing of gait, which is a sensation that their feet are stuck to the floor. Programming adjustments to account for this symptom include performing cardiorespiratory exercise on a stationary bike and using machine-based resistance training.

- Fatigue can be an issue for clients with Parkinson’s disease, so be sure to look for signs of fatigue in your clients and provide ample recovery between exercises and workout sessions.

8. Employ strategies to monitor cardiorespiratory and muscular-training intensity.

Making sure that your clients are exercising at an appropriate and effective exercise intensity is always a primary concern for health and exercise professionals. However, this consideration is particularly important for individuals with Parkinson’s disease because these clients are generally older and are at greater risk of cardiovascular disease. Moreover, as mentioned earlier, it is common for clients with Parkinson’s disease to take various medications that can influence the cardiovascular responses to exercise, which make some of the traditional methods for monitoring exercise intensity less valid. Here are some excellent alternatives for monitoring exercise intensity:

Cardiorespiratory Training: The talk test is a practical way to identify ventilatory thresholds and helps to provide individualization to cardiorespiratory training. To implement the talk test, pay close attention to the ability of your client to talk as they are exercising. As exercise intensity increases, talking will become more difficult as the client nears the first ventilatory threshold. Eventually, talking will become uncomfortable as the client gets closer to the second ventilatory threshold. Beyond the second ventilatory threshold, clients will have great difficulty talking. In previous ACE-supported research, we found the talk test functions as a practical way to establish and monitor cardiorespiratory training intensity in participants of a community exercise program, including older-adult clients with Parkinson’s disease.

Muscular Training: In previous ACE supported research, when prescribing muscular training intensity, we have successfully used a percentage of five-repetition maximum (5 RM). Rating of perceived of exertion (RPE) is also a viable approach to establishing muscular-training intensity for older adults with chronic conditions. In general, resistance-training intensity should elicit a moderate-to-high RPE of 5–6 and 7–8, respectively, when using a 0–10 point scale.

9. Incorporate regular balance training.

Emphasize balance training and fall prevention for all clients with Parkinson’s disease. Clients who have fallen at least once within the past year are likely to fall again in the next three months. The frequency, intensity, time and type (F.I.T.T.) approach to exercise programming used for cardiorespiratory and muscular-training program design can also be applied to balance exercise programming. Balance training should be performed three days per week for 10 to 15 minutes per session at an intensity that is safe, but challenging. Balance training should be integrated into the overall exercise program, ideally before resistance and flexibility activities.

10. Adequately progress balance and fall-prevention exercises.

Research suggests that balance training programs that include only single-task activities fail to place the client in an environmental condition similar to what they experienced prior to and during a fall. For this reason, consider designing balance and fall-prevention exercises that combine balance exercises with additional tasks; this is referred to as dual-component training. For example, in addition to performing heel-toe walking, have the client simultaneously complete a cognitive task such as counting backwards from 100 by increments of three. Another form of dual-component training might involve combining a balance exercise with another physical form of activity, such as balancing on one foot while playing catch with a light medicine ball. A word of caution: Take care with novice clients who have Parkinson’s disease and be sure to progress the exercises appropriately (Table 1).

Table 1. Balance and Fall-prevention Exercises and Training Progressions

|

Position

|

Balance Exercise

|

|

Sitting

|

Sit upright and complete the progressions listed below.

|

|

Perform leg activities (heel, toe or single-leg raises, marching).

|

|

Standing

|

Clock: Instruct client to balance on one leg. Call out the time and have client move their non-support leg to the time called (e.g., 5 o’clock, 9 o’clock). Alternate legs.

|

|

Perform leg activities (heel, toe or single-leg raises to a 45° or 90° angle, marching).

|

|

Spelling: Instruct client to balance on one leg. Ask the client to spell a word (e.g., client’s name, day of week, favorite food) using their non-support leg. Alternate legs.

|

|

In Motion

|

Perform heel-to-toe walking along a 15-foot line on the floor (first with and then without a partner).

|

|

Excursion: Lunge over a space separated by two lines of tape, alternating legs with each repetition. Progress to hopping or jumping (using single-leg or double-leg) back and forth across the space.

|

|

Dribble a basketball around cones that require the client to change direction multiple times.

|

|

Training Progressions

|

Arm progressions: Use a stable surface such as a chair or wall for support; keep hands on thighs, hands folded across the chest.

|

|

Surface progressions: chair, balance disks, foam pad, stability ball

|

|

Visual progressions: open eyes, sunglasses or dim room lighting, closed eyes

|

|

Tasking progressions: single-tasking, multitasking (e.g., balance exercise + pass/catch ball)

|

|

Note: The number of repetitions per exercise and rest intervals will be dependent on client conditioning and functional status.

|

Regular exercise has been shown to lessen the progression of Parkinson’s, help manage its symptoms and improve overall quality of life. If you want to learn more about this disease and how to work with individuals who have Parkinson’s, check out these highly regarded resources: