The Link Between Exercise and a Healthy Gut

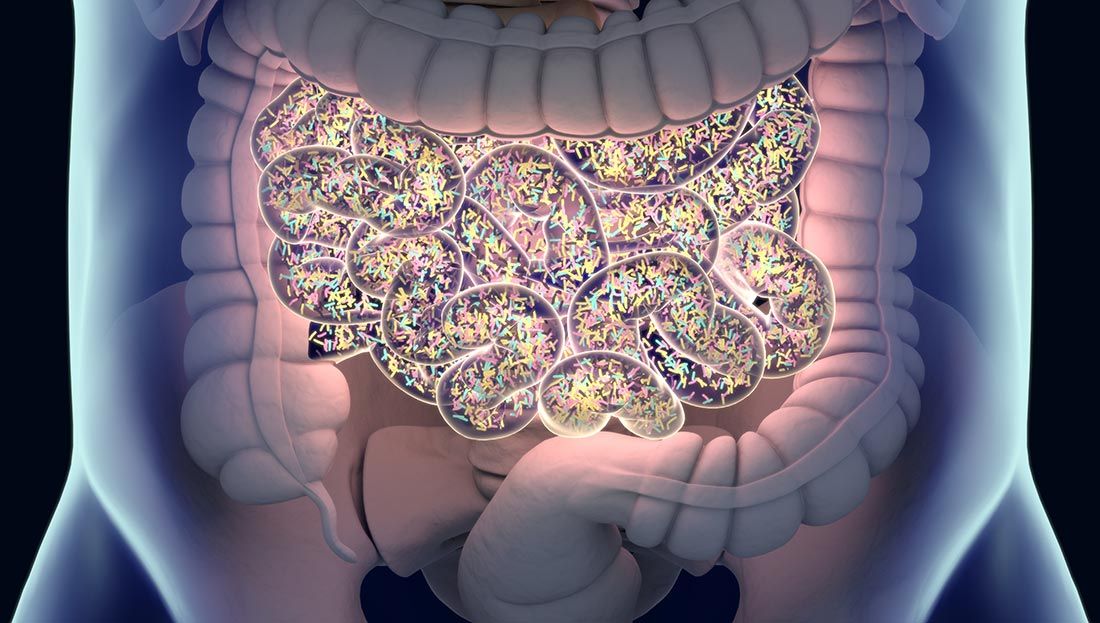

Microscopic gut bacteria and the gut microbiome have been getting a lot of attention lately, from both researchers and consumers alike. As a growing area of research, it can be challenging to understand the science or know how to separate the hype from the reality. For example, do you actually know what a “gut microbiota” is and why it’s so important when considering your clients’ health and wellness? And did you know that cardio alone can vastly alter this microbiota balance for the better? Read on to learn the answer to these and other pertinent questions related to the gut microbiome and microbiota.

First, a little clarification of terms is in order. Registered dietitian nutritionist Aicacia Young, who serves as the director of scientific affairs for Microbiome Labs, explains the difference between gut microbiome and gut microbiota this way: “The gut microbiome is the environment, like a rain forest, in which bacteria and other organisms reside. Gut microbiota are all the organisms that live within that environment, like mammals, reptiles, birds and amphibians.”

Tens of trillions of tiny living microorganisms, consisting of thousands of different types of bacteria with more than 3 million genes, make up this microbiome. The microbiota, located in the intestines, can weigh up to 4.4 pounds and are unique to each individual, much like our thumb prints. Gut bacteria play a role in vitamin production, nutrient absorption, inflammation, chronic disease, metabolic conditions, mental health, weight fluctuations and much more.

Symptoms of an Unhealthy Gut Microbiome

“Gut health is more than just regular bowel movements and sufficient digestion,” explains Young. “The health of the gut is central to the health of the entire body. If you’re having trouble sleeping, changes in mood, difficulty concentrating, hormonal fluctuations, headaches, joint pain, skin irritations, intense cravings or bad allergies these are all signs of an imbalance in the gut microbiome.”

A lot of things can contribute to one’s gut becoming overridden with too many of the “bad guys.” Antibiotics, unhealthy food choices (e.g., highly processed foods, foods high in sugar, and alcohol), chronic stress and lack of sleep all contribute to an unfavorable intestinal change. In addition to what Young mentions above, some other common signs that something might be “off” with a client’s gut health include:

- frequent gas

- bloating

- diarrhea

- constipation

- heartburn

- increased sugar cravings

- unexplainable weight changes

- chronic fatigue or lethargy

- skin conditions such as eczema and acne

- autoimmune conditions

- food intolerances

As a health and exercise professional, you could potentially have a part to play in improving your clients’ gut health. This is where a structured cardiorespiratory exercise regimen comes in. This article details why endurance exercise is so important for gut health and how to optimally help all of your clients improve their gut microbiota, regardless of where their starting point might be.

How Exercise Can Impact Gut Health

“Cardiorespiratory fitness, or the body’s ability to efficiently deliver oxygen during exercise, is associated with greater bacterial diversity in the gut,” says Young. And a growing body of research is helping to explain why that is.

For example, one study published in 2017 examined the effects exercise on gut health using three groups of mice: a sedentary group, a group with access to a running wheel and a sedentary germ-free group. After six weeks, fecal matter from both the exercise and sedentary groups were transplanted into the germ-free group. The mice were then given a chemical to trigger colitis (inflammation of the colon). According to the researchers, the mice that received a fecal transplant from the active group saw a faster reduction in inflammation and a faster recovery overall.

A second study conducted by the same researchers explored the impact of weeks of endurance exercise on “composition, functional capacity and metabolic output of the gut microbiota” on sedentary lean adults and adults with obesity, with dietary controls in place. The 32 male and female participants underwent six weeks of supervised cardiorespiratory workouts. At the beginning of the study, endurance-based exercise was performed three days a week for 30 to 60 minutes at around 60% of heart-rate reserve (HRR) and progressed to a more vigorous 75% of HRR. Participants were asked to return to a sedentary lifestyle immediately after the six-week study period. Fecal samples were collected before and after the six-week exercise experiment, and then again after the sedentary six-week period. Participants were asked to maintain their usual diet throughout the entire study period.

While no two people showed the exact same changes, the researchers noticed some trends. Most participants saw an increase in microbes that can help produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). SCFAs are important because they help to reduce inflammation throughout the entire body, combat insulin resistance, promote gut health and increase regenerative molecules to speed up recovery. The lean group saw a much higher jump in SFCAs upon exercising, but the study noted that they were much lower to begin with (more research is needed to explain why).

After returning to a sedentary lifestyle for six weeks, all positive effects dissipated and all of the participants’ gut microbiomes returned to what they had been prior to the exercise experiment.

In other words, exercise is beneficial for gut health, but only for as long as one continues to do it. When someone stops exercising, the gut benefits stop.

What Exercise Benefits the Gut the Most?

So how exactly can you coach your clients into achieving their fitness goals while also possibly positively impacting their gut health?

Another study examining the connection between cardiorespiratory fitness and microbial health included 39 healthy participants of similar age, body mass index (BMI) and diets, but with varying cardiorespiratory fitness levels. Researchers measured and compared peak oxygen uptake (VO2 peak) to participants’ fecal samples. They found that the more fit individuals had higher levels of butyrate, a SCFA, and concluded that “cardiorespiratory fitness is correlated with increased microbial diversity in healthy humans...[and] the microbial profiles of fit individuals favor the production of butyrate.” The researchers also recommended that exercise should be used as an adjuvant therapy for those who have a microbial imbalance or other dysbiosis-related condition.

These studies focused on cardiorespiratory activity due to the very specific response it elicits in the body. Based on the type of exercise one performs, a very particular set of cellular sensors are triggered and, thus, different targeted genes are expressed. The genetic pathway that’s activated during resistance training triggers an increase in protein synthesis leading to muscle growth. However, with cardiorespiratory exercise, a different genetic pathway is activated that triggers protein synthesis in other tissues, which increases the number of mitochondria. This is important because research is now showing an apparent cross-talk between the body’s mitochondria and gut microbiota during cardiorespiratory exercise, suggesting that this form of training is the way to go for improving gut health.

How to Apply the Research to Your Work With Clients

Based on these studies showing the positive impact that cardiorespiratory exercise can have on altering the gut microbiota, it may be worth considering the type and frequency of cardio you’re programming for your clients. Tracking HRR and maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) during cardio exercises and assessments, as was done in two of the studies above, are quantifiable ways to monitor a client’s intensity. This information is another way to shift cardio’s long-standing focus from calorie burning to gut-health enhancement and disease prevention.

“Collectively, the available data strongly support that, in addition to other well-known internal and external factors, exercise appears to be an environmental factor that can determine changes in the qualitative and quantitative gut microbial composition with possible benefits for the host,” write the authors of a report published in Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. They assert that exercise is able to enrich the microflora diversity, which offers a whole host of benefits (as discussed earlier). “In addition, exercise-altered microbiota could be used to look for new approaches in the treatment of metabolic and inflammatory diseases in which it is well known that the microbiota play an important role.”

Clearly, cardiorespiratory exercise plays a vital role in a fitness program, not only for helping clients maintain a healthy weight, but also for improving overall health and well-being by enhancing gut microbiota. Regardless of your clients’ current gut microbiota status, these studies suggest that adding cardiorespiratory training can help increase SCFAs, which may facilitate a multitude of health benefits, including inflammation reduction and improved gut health.

More Articles

- Certified™: June 2019

ACE-SPONSORED RESEARCH: The Accuracy of Heart Rate–based Zone Training Using Predicted versus Measured Maximal Heart Rate

Contributor

- Certified™: June 2019

Medicine Balls: An ACE Integrated Fitness Training® Model Workout

Health and Fitness Expert

- Certified™: June 2019

Is There a Ceiling to Success for Group Fitness Instructors?

Health and Fitness Expert

by

by