In two previous articles, we explored how to use the ACE Integrated Fitness Training® (ACE IFT®) Model to (1) help someone with a sedentary lifestyle establish an exercise habit and (2) improve athletic performance. In this third article in the series, we explain how to work with clients who are re-entering the fitness facility after some sort of rehabilitation or medical treatment.

These “post-rehab” clients may be coming to you from any of a number of situations, including orthopedic rehab (which might include surgery and/or physical therapy), cardiac rehab following a heart attack or other cardiac event, or cancer treatment (which might include multiple surgeries, chemotherapy and/or radiation treatment).

While some health and exercise professionals might be hesitant to work with these clients, a skilled practitioner can use the ACE IFT Model to conduct the appropriate assessments and then create a program that is both safe and effective.

Three Essential Steps to Working with a Post-rehab Client

Regardless of a client’s specific situation, there are three key steps that must be completed when working with any post-rehab client.

Step 1 is to obtain a medical clearance and referral that provides details on what treatment the client has completed, including procedures or surgeries that could impact his or her ability to perform certain movements. The referral should list any restrictions, contraindications and guidelines.

The following cannot be stated emphatically enough: You must adhere to the instructions provided in these documents, primarily to ensure the safety and health of the client, but also to protect yourself legally. For example, if a client comes to you after shoulder surgery, the doctor may note that overhead lifting movements are contraindicated for the first six weeks after surgery. You might feel after four or five weeks that the client seems very strong and is ready to be challenged, but allowing that client to perform a contraindicated movement not only risks serious setbacks or even re-injury, it also means that you would be liable for any damage done as a result of you overstepping your scope of practice.

It is also important to note that many post-rehab clients will have complicating factors of which you may not be aware, or that will have an impact on physical activity that you might not anticipate. For example, a client who joins a fitness facility after breast cancer treatment may have limitations related to the type of surgery he or she had, whether lymph nodes were removed and any tissue damage resulting from radiation treatment. The possibility of limitations that may not be obvious is a key reason why understanding and then adhering to the guidance of each client’s medical team is absolutely essential.

Step 2 is to examine the client’s most recent rehabilitative exercise program. This will serve as your starting point, and a baseline against which to compare future progress. Having knowledge of what was being done in a physical therapy or occupational therapy setting can guide the types and intensities of movements you program for your client. That said, be mindful of your scope of practice—a recurring theme when working with post-rehab clients—as certain things done in those settings, such as manual treatments or massage therapy, are inappropriate and may be illegal for an exercise professional.

Step 3 is to maintain communication with the medical team, which might include a primary care physician, healthcare specialists (such as an oncologist for someone coming to the gym post–cancer treatment) and any physical or occupational therapists. It is up to you to find out with whom you should be communicating and how that back-and-forth exchange should take place.

These three steps hold true for any post-rehab client, but the truth is that some of these clients are more likely to exercise at a typical fitness facility than others. Individuals who are post–cardiac rehab or have undergone prolonged cancer treatment, for example, may exercise at a medical fitness facility under strict guidance and oversight. The type of post-rehab client with whom health and exercise professionals are most likely to work are those with orthopedic concerns, which are the focus of the remainder of this article.

Communicating Using SOAP Notes

Being concise in your communication with members of the medical team is a marker of professionalism. The SOAP note—which stands for Subjective, Objective, Assessment and Plan—efficiently communicates vital information to all team members without being overly cumbersome for anyone involved. Content for each section of the SOAP note as used by exercise professionals is defined as follows:

- Subjective: Observations that include the client’s own status report, a description of symptoms, challenges with the program and progress made

- Objective: Measurements such as vital signs, height, weight, age, posture, and exercise and other test results, as well as exercise and nutrition log information

- Assessment: A brief summary of the client’s current status based on the subjective and objective observations and measures

- Plan: A description of the next steps in the program based on the assessment

The SOAP note is an elegant and efficient way to communicate both what the client feels and what you observe. Over time, SOAP notes document patterns of self-image versus actual performance, and can be useful tools when providing feedback to the client.

The frequency of contact is somewhat established by those with whom you communicate on a regular basis. Typically, team members should expect to receive updates every four to six weeks. More frequent communication may be perceived by the team member as offering too much contact without being able to report on actual change, while communication that takes place less frequently than about every eight weeks runs the risk of being forgotten.

Working With Clients After Orthopedic Rehab

Imagine your new client comes to you from physical therapy a few months removed from knee surgery. You’ve taken the three steps outlined above, so you understand his contraindications and restrictions, know the basic elements of his most recent workout routine and have established communication with his doctor and physical therapist. What comes next?

As with any client, you should discuss things like his goals, background and interests. Ask the client to tell you the story of his rehab, and then discuss any current symptoms, triggering movements and levels of soreness and swelling. Note that this information should be shared with the medical team.

Functional Movement and Resistance Training

Working with post-rehab clients requires an understanding of how people move as well as an exploration of the mechanism of injury, asserts Pete McCall, M.S., faculty in the Exercise Science Department at Mesa College and an ACE Certified Personal Trainer. An athlete who suffered an acute injury during competition will have very different needs than someone coping with a repetitive stress injury as the result of factory work or a sedentary individual dealing with the aftermath of a car accident.

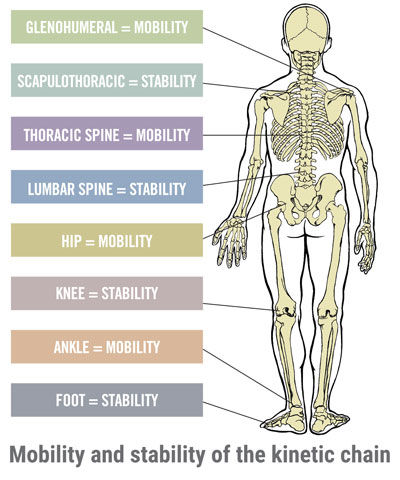

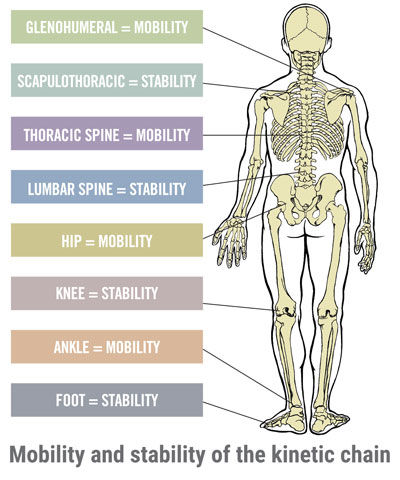

Once you have an understanding of the individual client, it is time to perform a series of assessments. Note that most post-rehab clients will be starting in phase 1 of the Functional Movement and Resistance Training component of the ACE IFT Model, which involves stability and mobility training, with a goal of progressing into movement training, which is phase 2. Load training (phase 3) may be a long way off. Therefore, you should start by having the client perform basic movements to identify a safe range of motion, evaluate posture and balance, and examine stability and mobility throughout the kinetic chain.

Most post–orthopedic rehab clients will have stability and mobility issues in the affected limb, especially if they are overcoming a lower-limb injury. The client may limp or favor one side during walking gait, thereby altering how he or she is using muscles throughout the body.

If a client has completed rehabilitation for a knee injury, you should use the rehabilitated knee as your guide, explains Todd Galati, M.A., ACE’s Senior Director of Science and Research. “Stability in the affected knee is going to be compromised, while the neighboring joints in the kinetic chain—that is, the ankles and hips, may have compromised mobility resulting from providing compensatory stability to support the affected knee joint,” Galati explains. “Don’t let movements in the healthy joints push the affected knee to a place where the injury becomes re-aggravated.”

McCall echoes this idea, reminding you to be cautious about overloading other parts of the body. “The entire chain works together,” he says, “and each link affects the function of all of the others. It is essential that everything is working together before adding external loads or pushing movements too far.”

You may have to modify certain exercises to stay within a client’s functional range of motion. For example, instead of performing full squats, a client overcoming a knee injury may have to begin with hip hinges or quarter-squats, in which case you can use that as a baseline to demonstrate improved range of motion later on in the program. You may also encourage clients to keep one hand on a stable support, such as a ballet barre or wall. Maintaining stability throughout the range of motion, even when that range is limited, is critical for both post–orthopedic rehab and healthy clients.

You may have to modify certain exercises to stay within a client’s functional range of motion. For example, instead of performing full squats, a client overcoming a knee injury may have to begin with hip hinges or quarter-squats, in which case you can use that as a baseline to demonstrate improved range of motion later on in the program. You may also encourage clients to keep one hand on a stable support, such as a ballet barre or wall. Maintaining stability throughout the range of motion, even when that range is limited, is critical for both post–orthopedic rehab and healthy clients.

Your role as a health and exercise professional is to build off the client’s therapeutic program by working through a stability/mobility program that addresses the entire kinetic chain, not just the rehabilitated joint. It is important to focus on both the affected and unaffected limb to help restore balance. Also, let the client know that it may take weeks, or even months, to progress from stability/mobility training to movement training.

Remind the client that you are trying to “reestablish normal,” which takes time. To help keep clients motivated, focus on small victories that illustrate the progress being made: “Remember, when we first met that you had to use your arms to get up out of a chair to compensate for weakness and instability in your legs. Now you’re much more stable and your strength is building week to week.”

If you are working with a particularly driven client—an athlete hurt during competition is likely to be much more motivated to work hard than a previously sedentary client who got hurt slipping and falling—you can challenge other areas of the body to keep him or her focused. For example, in the case of a client following rehabilitation for a knee injury, you can work on upper-body training while seated on a bench or piece of resistance-training equipment.

Cardiorespiratory Training

As with Functional Movement and Resistance Training, the first step with Cardiorespiratory Training is to review the program the client was following during rehab and then gradually build on that program, which likely featured walking and/or stationary cycling, depending on the type of injury. These clients are typically in phase 1 of the Cardiorespiratory Training component of the ACE IFT Model, which is aerobic-base training. That said, if the client is a cyclist with an upper-body injury, for example, he or she may be able to perform more difficult workouts on a stationary bike.

Galati points out that, in addition to the usual cardiorespiratory benefits, post-rehab clients will experience circulatory benefits (e.g., the delivery of nutrients and removal of waste product in the injured area) and increased muscular endurance. “This improved muscular endurance,” he explains, “will serve as the foundation for movements that clients perform throughout the day.”

Be sure that the client’s program features modalities that fit within the recommendations from the medical team. For example, the referral may say something like “no running until the three-month evaluation.” In such cases, you must strictly adhere to those guidelines, for both safety and legal reasons.

You can allow post-rehab clients to progress with their cardio workouts as you would any other client, as long as you remain mindful of avoiding contraindications and restricted movements, and progress slowly and avoid potentially re-aggravating the injury. You may need to adjust the seat height on certain machines to limit the movement to a pain-free range of motion.

McCall suggests having post-rehab clients perform circuit training, and progressing those workouts by shortening the rest intervals rather than making the exercises themselves more taxing. This will elevate the heart rate and require the client to utilize more oxygen without placing too much strain on the injured joint.

In Conclusion

The primary focus when working with any post-rehab client is reestablishing proper movement form. The key is to train the entire system by strengthening the muscles that surround and support the affected joint and coordinating that movement throughout the kinetic chain.

McCall offers one more piece of advice: You may think that your role when working with post-rehab clients is to be super-motivational and push clients to work through their injuries. In fact, in certain facilities, many of these clients may be current or former athletes who may be too eager and want you to push them too quickly. In those situations, your role is to pull back the reins and help them avoid overdoing it. It all comes down to understanding your client’s needs, respecting the involved medical professionals’ guidelines and individualizing your programming.

by

by

You may have to modify certain exercises to stay within a client’s functional range of motion. For example, instead of performing full squats, a client overcoming a knee injury may have to begin with hip hinges or quarter-squats, in which case you can use that as a baseline to demonstrate improved range of motion later on in the program. You may also encourage clients to keep one hand on a stable support, such as a ballet barre or wall. Maintaining stability throughout the range of motion, even when that range is limited, is critical for both post–orthopedic rehab and healthy clients.

You may have to modify certain exercises to stay within a client’s functional range of motion. For example, instead of performing full squats, a client overcoming a knee injury may have to begin with hip hinges or quarter-squats, in which case you can use that as a baseline to demonstrate improved range of motion later on in the program. You may also encourage clients to keep one hand on a stable support, such as a ballet barre or wall. Maintaining stability throughout the range of motion, even when that range is limited, is critical for both post–orthopedic rehab and healthy clients.