The word “core” gets thrown around a lot, and there is a lot of variation in exactly what most people mean when they use the term—and how to properly train it. As a health and fitness professional, you know the importance of core strength, but are you completely clear on what muscles make up the core and how to train to avoid imbalances? And are you following a safe progression of exercises when it comes to core strengthening?

Like many of your clients, you may have a few questions about this all-important area of the body. Well, here are some much-needed answers…

Core Muscle Make-up

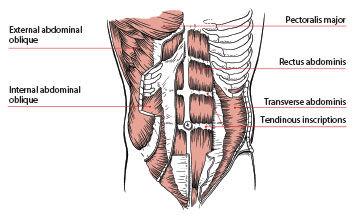

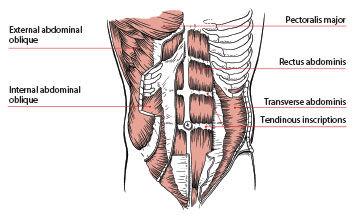

The core is divided into two separate units, each of which has its own unique purpose. Knowing the function of each unit and what muscles make up the core as a whole will help guide you in designing safe, effective exercise progressions for your clients.

“The inner unit is mostly used for fine segmental stabilization of the spine,” explains Eric Wilson, a personal trainer and corrective exercise specialist based in Apex, N.C., “whereas the outer unit provides more mobility, gross stabilization and motor control during high-intensity exercise, such as deadlifts, throws or sprints.”

While some experts differ on the exact muscle groups included in the core, there is a general consensus. According to Wilson, who was named the 2016 Biomechanics Method Corrective Exercise Specialist of the Year, “The inner unit is composed of the transverse abdominis, [the posterior fibers of the internal] obliques, diaphragm, pelvic floor muscles, and lower back muscles, including the multifidus, longissimus and illiocostalis. The outer unit is composed of the rectus abdominis, spinal erector muscles, external and internal obliques, quadratus lumborum, and technically even extends down into the glutes, hip flexors and hamstrings.”

Unit Imbalance

It is not uncommon for the outer core unit to be stronger than the inner unit.

“The inner-core muscles in many people are weakened for several reasons,” explains Samantha Clayton, owner of Samantha Clayton Fitness and a former Olympian. “A sedentary lifestyle of sitting at desks all day means that these essential muscles are no longer being challenged with activities of daily living as they were in the past. Secondly, people training for recreation in the gym often neglect these muscles and train the ‘mirror muscles,’ [which leads to] creating imbalances over time.”

Clayton, a mother of four, including a set of triplets, cites another cause of core unit imbalance: pregnancy and childbirth. “The outer core is affected, too, but the pelvic floor is especially a problem area. I can share from personal experience that the inner-core muscles are especially weakened with pregnancy and require rehabilitation post-pregnancy in order to regain their former strength. You just have to say ‘jumping jack’ to a new mom and the thought alone will have her running to the bathroom."

Wilson believes that there is another reason for inner and outer unit muscular imbalances. “I have also found through a lot of personal experience that it is not so much the strength that can be the issue, but the lack of neurological recruitment of inner-unit muscles,” she explains. “The brain is not used to needing to fire the muscles as rapidly or efficiently and this can cause more injuries to people than just the lack of strength itself, as the spine is not quickly stabilized when movements are initiated.”

Too Much Too Soon

As Clayton points out, many people tend to work the “mirror muscles”—the ones that can be seen on the outside of the body—and often the anterior muscles more than the posterior, especially where the core is concerned. There is also a tendency to progress through core strengthening faster than the exerciser may be ready for, introducing advanced exercises too soon. In this case, because the outer unit is stronger or more advanced neurologically, it takes over and the inner unit is neglected, further exacerbating the muscular imbalance between the two units.

“Your core is [made up of] muscle,” says Dustin Raymer, M.S., fitness director for Structure House in Durham, N.C., “and like any other muscle, it needs a starting point and then you can work your way up to heavier or more intense training. If not, this could lead to tears or even hernias.”

Wilson agrees. “I see many people who are progressing into extremely difficult ab exercises, such as sit-ups, ab rollouts and hanging leg rises without having an understanding of form or coordination of the exercise,” says Wilson. “While I understand the allure of wanting great-looking abs, it is usually done at the cost of spine health.”

Clayton echoes the assertions of both Raymer and Wilson, saying that while attempting advanced ab work too soon may not be a problem initially, it will catch up to your clients over time.

“It's a catch-22 for many trainers. The stabilization work that is essential for building a balanced body is quite often the least exciting and less ‘sexy’ part of a workout. Because of this, trainers don’t want to bore their excited new clients by having them do exercises that don’t really feel like exercise—or, to be more precise, what they perceive exercise should be based on the media's depiction. It takes almost a deconditioning process of the mind to get someone on board with doing the little things that will make a big difference in the long run.”

Safe Progressions

One of the first lessons you can teach your clients is that they can actually work the core muscles all day long—and should.

“One of the most effective ways to train the inner core,” explains Raymer, “is to constantly think about bracing the core while doing other exercises that require higher stability, such as squatting or overhead pressing.”

“My mindset for the core is that your core is always working,” agrees Clayton, “even when you’re doing the fun stuff like squats, step-ups and lunges, so make your clients aware of how to maximize their efforts.”

Clayton uses the mantra "Locate, Activate, Move” to help her clients understand how to activate their core muscles. For example, she has a client stop and “locate” the transverse abdominis muscle, “activate” by pulling the belly button through to the spine, and then finally “move” and perform the exercise.

You could also encourage your clients to perform a Kegel—a contraction of the pelvic floor muscles—before doing a jump squat. “It's simply a ‘tighten your safety belt’ approach to movement,” Clayton explains. “I encourage trainers to think of creative ways you can encourage this new ‘body aware’ training method of using good form and starting all movement in your mind before taking a single step.”

As far as actual core exercises, think of the inner unit as the core’s foundation, which must be strong before progressing to building on it. “My favorite progression,” says Wilson, “is to start with coordination, then stabilization and then strength.”

As an example, Wilson teaches every client the cat/cow exercise from yoga. “I want to make sure they can feel the muscles that control their pelvic position,” he explains. “This is a huge foundation exercise that carries over into a large majority of the exercises we do in the gym. Once they have mastered the pelvic control, I then work on segmentally controlling the spine, making sure they can tilt the pelvis, lumbar spine and thoracic spine independent of each other [while] in the quadruped position.”

To initially work the spine stabilizing muscles, Wilson focuses on the pelvic floor muscles and transverse abdominis. These exercises can include prone ab vacuums, birddogs and wall sits with arm raises. “Once they can perform these correctly, we can progress to plank, first starting on the knees and then progressing to on the toes, eventually adding some weight onto their hips.”

Beware of making a client hold a position, such as the plank, for a designated length of time. For example, if you tell a client to hold the plank for one minute, but after 10 seconds, the abdominal muscles are no longer engaged, you’re defeating the purpose of the exercise.

Beware of making a client hold a position, such as the plank, for a designated length of time. For example, if you tell a client to hold the plank for one minute, but after 10 seconds, the abdominal muscles are no longer engaged, you’re defeating the purpose of the exercise.

Wilson urges trainers to work their way backward. “For instance, if you know that in three months, your client wants to be able to hold a two-minute plank, you can work your way backward and set out a game plan to get there. Have certain thresholds and goals along the way, such as making sure the client can hold a plank for 30 seconds on her knees without the spine buckling. The first time she tries to progress, watch her form like a hawk,” Wilson urges. “As soon as you see her back start to buckle or the shoulders sink, stop her and explain what happened and ask if she could feel when the abs gave out or when her form broke. This not only helps the client understand what improper form feels like, but also reinforces the principle that you never want to perform an exercise with improper form.”

Clayton suggests you ask yourself the following questions when deciding whether or not to progress a client to the next level of difficulty with core work:

- What is the standard for this exercise?

- What is the client's goal?

- Can he or she do the exercise safely?

- Is the client stable when doing it? Do you detect instability?

- Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

- Is the exercise comfortable for the client or is it too difficult? If so, do you need to choose something else that accomplishes the same goal?

Don’t forget that it is your responsibility as the health and fitness professional to help your clients build a strong foundation of stability, mobility and strength—and not just develop “mirror muscles” that look good, but result in poor functioning.

“Inspire, motivate and be creative,” encourages Clayton. “Get your clients to where they want to be by building confidence with layered movements.” And take the time to educate your clients about the reasoning behind your approach, so they understand the progression and why it’s important to build a strong foundation before moving on to other, more advanced exercises.

by

by

Beware of making a client hold a position, such as the plank, for a designated length of time. For example, if you tell a client to hold the plank for one minute, but after 10 seconds, the abdominal muscles are no longer engaged, you’re defeating the purpose of the exercise.

Beware of making a client hold a position, such as the plank, for a designated length of time. For example, if you tell a client to hold the plank for one minute, but after 10 seconds, the abdominal muscles are no longer engaged, you’re defeating the purpose of the exercise.