Have you ever taken a long walk on a hot day and felt your hands and fingers swell up? This uncomfortable feeling, caused by an expansion of blood vessels, is a key component of the body’s natural cooling system. As these vessels expand, your lymph fluid is filling up these spaces to help keep your body at a consistent temperature. If you are an individual with a healthy lymphatic system, this fluid quickly returns into the body as you cool down or pump your hands.

For an estimated 3.8 million American breast cancer survivors, however, this swelling may be persistent and is known as breast cancer−related lymphedema (see sidebar). In fact, for the one in five women who develop breast cancer−related lymphedema, this is both emotionally and physically challenging. Once diagnosed, lymphedema is considered chronic and often requires an intervention. This may include treatment with a certified lymphedema therapist, and ongoing interventions such as bandaging, compression garments and pneumatic pumps may also be required.

As a health and exercise professional, you can play an essential role in risk reduction for your clients, as well as being an additional resource for management. As is the case with so many areas of health and wellness, ongoing research brings new insight and understanding, often rendering what were previously standard recommendations as obsolete or outdated. In fact, the guidelines for prevention, risk reduction and supporting the management of lymphedema have evolved considerably over the past 30 years. For example, surgeries have become less invasive, radiation treatment is more targeted, and we have a better understanding of how movement impacts the lymphatic system and how lean muscle mass assists the movement of lymphatic fluid. This article includes the most up-to-date, research-based information on lymphedema to help you and your clients make appropriate choices related to physical and lifestyle activities and exercise programming.

The Connection Between the Lymphatic System and Breast Cancer Treatment

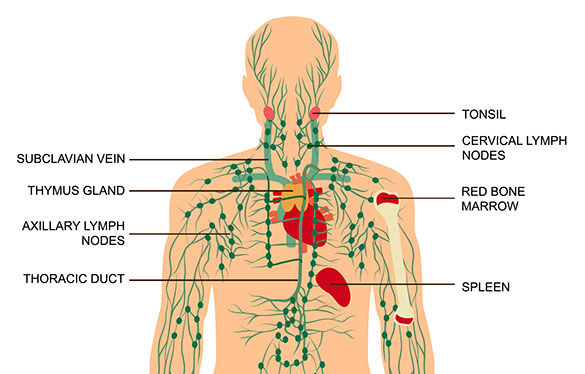

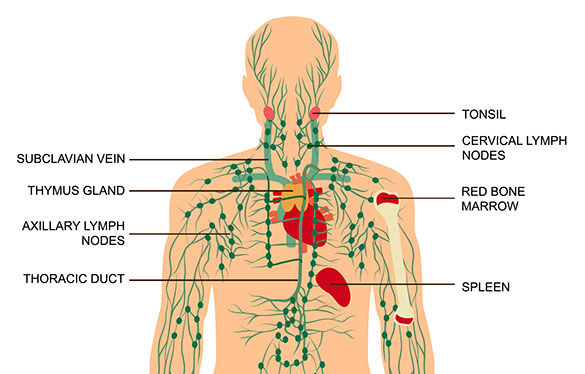

Along with temperature regulation, the lymphatic system has several jobs, including absorbing fats from the digestive system, stimulating the immune system and carrying waste from the body. Lymph nodes, the bean-shaped glands that filter and clean out damaged cells, including cancer cells, are also part of the lymphatic system. The human body has between 500 and 700 lymph nodes concentrated in areas such as the chest, abdomen and groin.

Lymphatic system

Until something like puffy hands, a fluid-filled blister or a swollen node in the neck occurs, most of us are only dimly aware of our lymphatic system. Although a heathy lifestyle that includes regular physical activity, adequate fluid and a balanced diet supports your lymphatic system, trauma to the lymphatic system may occur, causing long-term challenges and symptoms.

As part of a surgical work up for breast cancer, axillary lymph nodes are removed and examined for cancer cells that may have traveled outside of the breast. This is known as a lymph node biopsy. Removing lymph nodes creates trauma to the lymphatic system and may compromise the body’s natural processes. Additionally, lifestyle factors such as smoking and obesity (most notably a body mass index greater than 30) negatively impact the lymphatic system. When the lymphatic system is already damaged, treatments such as radiation and some chemotherapies can also compromise it, leading to a higher overall risk of lymphedema.

The History of Lymphedema

In the early 1900s, individuals with breast cancer were faced with a five-year survival rate of less than 50%, with invasive surgeries as the priority treatment for new diagnoses of breast cancer. Mastectomies in the early 20th century included removal of the entire breast, pectoralis muscles, and up to 40 lymph nodes.

While this radical mastectomy improved survival, new physical challenges appeared. Loss of strength, function and mobility in the shoulder and pectoral region were common. With these surgeries, a new side-effect known as breast cancer−related lymphedema began to emerge. This chronic and debilitating condition only worsened when, in 1937, radiation treatments that targeted both the breast and axillary region were introduced. As of 2009, 42% of women who had undergone cancer treatment were diagnosed with lymphedema, nearly all in the first three years after their diagnosis.

For many women, the lymphedema may feel worse than the cancer itself. An arm or breast that swells up to twice its normal size causes not only physical and emotional discomfort but also creates new challenges, such as finding clothing with long sleeves that fits correctly. Early lymphedema treatments did little to bring about significant reductions, so the focus inevitably shifted to developing guidelines that would help prevent the onset of lymphedema. Many of those earlier recommendations have since been rejected (see sidebar) in favor of evidence-based approaches that are more effective. As a health and exercise professional, it is important to be aware that historical, non-evidence-based guidelines are still circulated within clinical and fitness circles. It is helpful to be aware of both the previous and updated guidelines (discussed later in this article) to feel adequately prepared to support your clients.

History of Lymphedema Recommendations for Physical Activity, Lifestyle and Clinical Care

You might be surprised to learn about the recommendations women with lymphedema have been given over the years to help manage their condition. While many of these will seem arcane and maybe even a little ridiculous, it’s important to be aware of them because these recommendations persist, even decades after they’ve been discounted. For this reason, it is important for you to be aware of the types of information your clients may be receiving, particularly regarding physical activity.

For example, early physical-activity recommendations were very limiting and discouraged heavy or repetitive movements such as weightlifting and tennis. Additionally, activities that included arm-loading movements, such as downward-facing dog in yoga, and lifting heavy objects were to be avoided, and high-impact activities such as running were considered controversial. Wearing a compression garment was always recommended, even prophylactically for exercise, heavy yard work and home activities such as vacuuming, as well as for airplane and long-distance car rides.

Because infections are known to increase the risk of lymphedema, women were advised to not to shave their underarms with a razor or cut the cuticles on their fingernails. Saunas, hot tubs and using acupuncture were not recommended. Women were urged to avoid carrying a purse on their shoulder or wear bracelets and watches on surgical sides. Even clinical care was limited, with recommendations to avoid blood pressure cuffs, needle sticks or vaccinations such as the flu shot. Some patients were given a prescription for antibiotics to begin taking as a prophylactic measure, simply because they had a hangnail or paper cut that showed signs of infection.

It is worth noting that these recommendations were included for both individuals at risk of lymphedema and those who had already been diagnosed, as early recommendations did not discriminate between these categories. Even though lymphedema was most often diagnosed within the first two to three years, these were considered lifelong recommendations due to the permanent damage of the lymphatic system.

The Evolution and Role of Exercise

Over the past 20 years, exercise has become a standard recommendation in the care of every individual with cancer. In addition to quality of life, exercise has also been shown to improve breast cancer survival. In 2005, for example, a groundbreaking research trial showed that women who walked at a moderate intensity for 3 to 5 hours per week had an overall reduction of risk for dying from breast cancer or other diseases.

In parallel, cancer exercise researchers began to look at the role of exercise in helping to prevent and manage side-effects such as lymphedema and fatigue. A shift to early recovery after surgery provided the framework for updated recommendations, which include avoiding rest and instead engaging in activation of the shoulder and pectoral muscles to reduce pain, restricted shoulder mobility and lymphedema.

In 2009, a study that challenged previous restrictions related to resistance training made its way into the hands of oncology professionals across the world. The PAL (physical activity and lymphedema) study enrolled 154 women at risk for breast cancer−related lymphedema, assigning them to either a program of slowly progressive weight training, starting out with very light weights, or no exercise at all. Among women who had five or more lymph nodes removed, the weight training made a difference: Just 7% in the intervention group experienced an incident of lymphedema, compared to 22% in the no-exercise group.

This study reiterated the importance of resistance training to build essential muscle mass that can help act as a pump to move the lymphatic fluid back into the body. Returning to our earlier example, this process is not unlike pumping your hands and flexing your fingers at the end of a walk to help disperse the fluid that accumulates there. The PAL study reiterated what many oncology exercise professionals expected and offered some essential guidelines to help all levels of health and exercise professionals support individuals who are striving to improve their fitness while reducing their risk.

Currently, the American Cancer Society (ACS) and the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) recommend that anyone affected by cancer (in accordance with all age-related physical activity guidelines) should avoid inactivity, return to daily activities as soon as possible after surgery, and continue with their normal activities and exercise as much as they are able during and after non-surgical treatments. The recommendations include 150 minutes of moderate or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic exercise and two sessions of resistance training involving all major muscle groups weekly. (Note: Keep in mind that these recommendations are lacking the specificity that is necessary to provide high-quality individualized exercise programming for cancer survivors and do not consider the individual’s history, preferences and goals. Specific recommendations should be made in consultation with the client’s healthcare team.)

Table 1 summarizes the latest guidelines and highlights some of the fitness-, lifestyle- and clinically related questions that might come up with individuals who are at risk of lymphedema. If a client has been diagnosed with or has active lymphedema, it is essential to collaborate with their healthcare specialists to help guide the patient on personalized recommendations.

Table 1. Current Guidelines for Managing the Risk of Lymphedema Among Cancer Survivors

|

|

Latest Clinical Evidence

|

| |

|

|

General Guidelines for Exercise

|

Strive to meet the ACS/ACSM exercise recommendations of 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity, plus two total-body resistance-training sessions per week.

|

|

Compression Garment

|

It is not recommended that individuals wear compression garments prophylactically.

|

|

Types of Exercise

|

There are no general restrictions on the types of activities an individual may perform. If range-of-motion limitations persist, the client should request an evaluation with an occupational therapist.

|

|

Strength Training

|

Start low, progress slowly and focus on consistency.

|

|

Yoga

|

There are no limitations on practicing yoga. Clients should monitor loading movements, such as downward-facing dog, for pain or tightness.

|

|

Lifestyle

|

Keep hands and skin clean and free from infection. Cover cuts and scrapes with antibiotic ointment and bandages.

|

|

Purses and Backpacks

|

Reduce purse/backpack usage and size for six weeks, based on the surgeon's recommendations.

|

|

Jewelry

|

There are no specific recommendations regarding wearing jewelry, so make choices based on personal comfort.

|

|

Household Activities

|

Once a client has been cleared by their surgeon, they will likely have no restrictions on performing household activities and chores. Urge clients to monitor the arm for fatigue.

|

|

Baths, Sauna and Hot Tub

|

There are no limitations on these activities, but open cuts and sores should be monitored closely.

|

|

Acupuncture

|

There are no limitations on this activity, but any punctures should be monitored for irritation.

|

|

Clinical Care

|

If desired, have blood pressure measurements, needle sticks and vaccinations performed on the non-surgical side. This is more for patient preference, but is not necessary.

|

|

Blood Pressure

|

If desired, have blood pressure taken on the non-surgical side or ask for a manual cuff to be used. This is more for patient preference, but is not necessary.

|

|

Needle Sticks

|

If desired, have needle sticks and vaccinations performed on the non-surgical side. This is more for patient preference, but is not necessary.

|

|

Travel

|

Obtaining an antibiotic prescription prior to travel is not necessary.

|

|

Airplane Travel

|

For flights longer than two hours, try to elevate and pump hands above the heart 10 times every 30 minutes. Move feet in circles to encourage lymphatic flow.

|

|

Luggage

|

Be mindful while pulling or lifting luggage based on item weight, shoulder strength and range of motion.

|

Note: ACS = American Cancer Society; ACSM = American College of Sports Medicine

Case Study: Putting the Recommendations Into Action

Sharon is a 57-year-old woman who was referred to you by a current client. Sharon completed breast cancer surgery and treatment about three months ago. Her hair is starting to grow back but she does not feel that her normal energy has returned. She has a leadership role in a technology company and feels tied to her computer on most days. She enjoys being active and tries to get in as many steps as possible, but finds this difficult. She feels tired at the end of her workdays and is even more inactive on the weekends because she is trying to catch up on her energy.

Sharon had a bilateral mastectomy even though her diagnosis was only in the right breast. She just completed her final reconstructive surgery, which included implants positioned on top of her pectoral muscles. She had some delays in her healing and her reconstruction was delayed by several months. While she ultimately required smaller implants, she is pleased with the cosmetic outcome. Sharon had three lymph nodes removed; because two were positive for breast cancer, she also had a course of radiation. Her type of cancer is considered a hormone-positive cancer, so Sharon will take a hormone-blocker medication for 10 years to suppress any additional estrogen in her body.

Since her diagnosis, Sharon has gained weight, which is both frustrating and concerning to her because she understands that increased body weight is a risk factor that could increase the risk of her cancer returning. Her current body mass index (BMI) is 38 kg/m2. She also notices more weight gain in her abdomen and reports that she has mild low-back and knee pain.

Sharon is at risk for lymphedema due to her higher BMI, sedentary behavior, the removal of three lymph nodes and radiation treatment. Her delayed recovery post-surgery also increases her risk, but she has not had any concerns about breast or arm swelling and her oncology team has encouraged her to engage in a regular exercise program. Because Sharon is only at risk, she does not need to wear a compression garment to exercise.

After reviewing Sharon’s health-history information, the ACE Mover MethodTM philosophy can be used to enhance each client interaction by using coaching skills to help build rapport and position the client as an active partner in their behavior change journey. This method can be easily applied through the ACE ABC ApproachTM, which involves asking open-ended questions, breaking down barriers and collaborating on next steps. Step one of the ACE ABC Approach involves finding out what the client hopes to accomplish by working with you, the health and exercise professional, and what activities they enjoy.

Exercise Professional: What would you like to achieve through working with an exercise professional?

Sharon: I would like to have more energy, lose weight and reduce my risk of dying from cancer or other diseases. I think becoming more physically active will help me achieve these goals. I have had high blood pressure in the past, but this has resolved without medication. I do not smoke, and I usually have one to two alcoholic beverages each week.

Exercise Professional: It sounds like losing weight, having more energy and reducing your health risks are important to you and becoming more physically active is a means for working toward these goals. What types of physical activity do you enjoy?

Sharon: I don’t have much experience with exercise and being active, but I do enjoy walking and being outdoors. I try to get in an as many steps as I can throughout the day, but I think I also need a more formal plan to get me moving in the right direction.

Exercise Professional: You enjoy walking and are already trying to get in as many steps as possible daily, and having a plan would be even more helpful. What do you need to start doing now to move closer to your goals?

Sharon: I think I need some guidance on creating a plan for walking. I try to walk as much as possible, but this is challenging for me. I am so tired by the end of the day that I do not think I can exercise after work. And by the time the weekend rolls around, I am even more inactive, as I try to replenish my depleted energy levels.

Exercise Professional: Having low energy is a barrier to becoming more active and having a plan would be helpful for getting started. What do you already know about how much exercise you should be doing?

Sharon: I don’t know exactly how much I should be doing but I bet I am not doing enough. I know that I feel good when I exercise and afterward, but I need to find a way to fit exercise into my existing daily routine. Can you share with me information about how much exercise I should be doing?

Exercise Professional: Thank you for sharing with me what you already know about exercise. Current recommendations suggest that you accumulate 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic exercise, spread throughout each week. Also participating in resistance training on two days per week is recommended. It is important to remember that these quantities are not necessarily a starting point but a target to be progressed toward. In fact, research shows that some physical activity is better than none and any amount of physical activity for any duration leads to health benefits. Does this information make sense?

Sharon: Yes. I understand that these recommendations are a goal for me to work on and no matter what my starting point is, I will achieve some health benefits.

Exercise Professional: Now that you have this information, what will your next step be?

Sharon: To get started, I want to walk for 20 minutes on three days per week. I will walk at a track near my office. I even plan to walk to the track from my office and I have a coworker who is interested in walking with me. I think walking on my lunch break is a good idea because I know I will be tired after work. You mentioned I should be exercising at a moderate intensity—how will I know if I am working hard enough?

Exercise Professional: It sounds like you have a well-thought-out plan and that this is something you believe you can do! When it comes to monitoring exercise intensity, a very simple method is called the talk test. Simply put, if you can talk but not sing while walking, you are at the right intensity. If talking becomes challenging, you can slow your pace and if you are able to sing while walking you can pick up your pace. Does this make sense?

Sharon: Yes. Thank you.

Exercise Professional: What are your thoughts about doing resistance training?

Sharon: To be honest, this is where I think I need the most guidance from you, as I have little experience with using weights. You mentioned resistance training is recommended on two days per week and I would like to meet this goal. I would like to work with you two days per week before work. I thought we could meet on the days when I am not walking during my lunch break to better ensure I still have enough energy for work.

Exercise Professional: Meeting with you twice per week in the mornings works for me. I will use the information we have discussed today to create an initial, personalized exercise program for you, and we can adjust this program as we work together based on your goals. To be as efficient as possible to work within your busy schedule, we will be using an approach called circuit training that allows you to keep your heart rate elevated, while using appropriate exercises and loads that can be gradually progressed each week until we reach a goal repetition range. How does this sound to you?

Sharon: I like this plan and am looking forward to working with you. Is there anything I need to be aware of when it comes to the potential for me developing lymphedema?

Exercise Professional: Great question! Your health and well-being are very important and we will look out for any signs of lymphedema as we work together.

Sharon: Thank you for putting my mind at ease and for being patient as we discuss all this information.

Exercise Professional: You’re welcome. I look forward to meeting with you this week!

The initial program you design includes two to three sets of each movement, which you set up as a circuit to keep her heart rate elevated and make her workout more efficient due to her busy schedule. Each movement begins with body weight or the lowest weight available. If no signs of lymphedema appear in her arm and breast, she can increase the level of resistance by the smallest increment each week until she reaches a level at which 10 repetitions feels challenging.

The circuit includes squats, alternating reverse lunges, single-arm rows with a dumbbell, standing shoulder press, bench press with dumbbells, inchworm and a V-sit hold. You also work with her on balance, such as standing on one leg, and an overhead hold between sets. As she begins to increase her upper-body strength, she can add more weight to her squats and lunges, which also increases her heart rate.

By using the ACE Mover Method, you are acknowledging that the client is the foremost expert on themself, utilizing active listening skills, and genuinely viewing the client as being resourceful and capable of change. You are also following the ACE ABC Approach by asking open-ended questions, breaking down barriers, and collaborating on setting goals and next steps. As a result of following these steps, you can share relevant information when appropriate, while also respecting the client’s autonomy in the goal-setting process. You are still using your expertise to design a safe and effective exercise program that also considering the client’s own expertise, goals and values to enhance behavior-change strategies and promote program consistency. After 12 weeks, Sharon reports that she is now walking three times per week during her lunch breaks at a moderate intensity and has not missed single exercise session. Sharon has not experienced signs or symptoms of lymphedema and has been noticing that she has more energy on the days she exercises.

by

by