The Newest Index on the Block: The Hydration Index

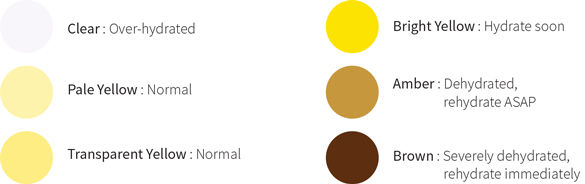

You’ve likely heard of the glycemic index and the insulin index, but beverages now also have their own index: namely, the new “hydration index.” People usually think about hydration in the context of sports and exercise, so it may be beneficial to know which beverages can best hydrate you when access to fluids (or bathrooms, see Figure 1 for a rough guide to bathroom-guided hydration statuses) is limited.

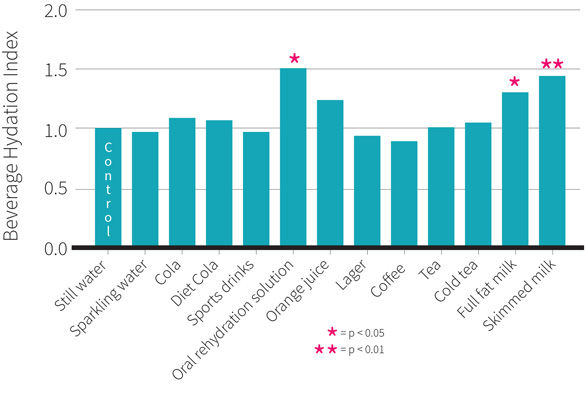

Figure 1: BHI for tested drinks

Not all beverages are created equal from a hydration standpoint. Absorption is affected by the amount of fluid ingested, electrolyte and carbohydrate content, and the presence of diuretic agents (substances that promote urine production). For example, milk has been shown to be more effective than both water and sports drinks for rehydration after strenuous exercise.

The rehydration process is affected both by the volume of fluid ingested as well as the sodium content. It has long been known that the presence of carbohydrates and electrolytes in a drink increase the rate of fluid absorption after drinking. Coffee is often thought of as negatively affecting hydration status, but this is based on studies examining the acute effects of high levels (more than 300 mg) of caffeine on individuals who had been deprived of caffeine for a period of days or weeks. A tolerance to the diuretic actions of caffeine develops with regular intake, and the amounts of caffeine found in normal-sized servings of tea, coffee, soda, etc., do not have diuretic effects.

This study is the first to develop a method for systematically quantifying values for hydration and fluid balance. Similar to how the glycemic index is intended to define the blood-glucose response to the ingestion of foods compared to a white bread or glucose standard, a beverage hydration index (BHI) could serve to quantify water excretion from the kidneys in response to various beverages compared with still water. The cumulative volume of urine passed over a fixed period of time can be measured as a marker of fluid absorption and retention. The aim of this new study was to determine the fluid balance responses to the ingestion of a set amount of commonly consumed beverages ingested in a euhydrated state (a normal fluid balance).

The volume and amount of electrolytes and sugars of ingested fluids affect their absorption and retention, but various beverages have yet to be systematically compared. This study set out to determine if a beverage hydration index, similar in principle to the glycemic index, could be established.

Who and What Was Studied?

This study recruited 72 recreationally active, healthy male participants between the ages of 18 and 35. A large number of participants were needed due to the study design, which tested 13 different beverages. Each participant completed a maximum of four experimental trials that included water along with three other test drinks. Participants recorded their diet and exercise during the two days before the first trial and were asked to replicate it before their subsequent visits. They were also asked to avoid strenuous exercise and alcohol in the 24 hours preceding all trials.

Participants consumed 500 milliliters of still water over the course of 15 minutes, one hour before arriving at the laboratory. This is potentially problematic because they were self-guided, so compliance could have been poor. After using the bathroom and performing baseline bodyweight measurements at the lab, participants ingested one liter of the assigned test drink over a 30-minute period (four equal servings administered 7.5 minutes apart). They were then asked to empty their bladder at the end of the drinking period and again at the end of each hour for the next four hours.

The following drinks were tested:

- Still water

- Sparkling water

- Coca-Cola

- Diet Coke

- Sports drink (Powerade)

- Oral rehydration solution (Dioralyte)

- Orange juice

- Lager beer (Carlton)

- Hot black coffee

- Hot black tea

- Cold black tea

- Full-fat milk

- Skim milk

Even though a set volume of each beverage was consumed, the presence of other components (e.g., fat, carbohydrate, protein) means that the actual water content of the drinks was between 88 to 100 percent. Results are presented both corrected and uncorrected for the differences in water content, as practical use would dictate the uncorrected values.

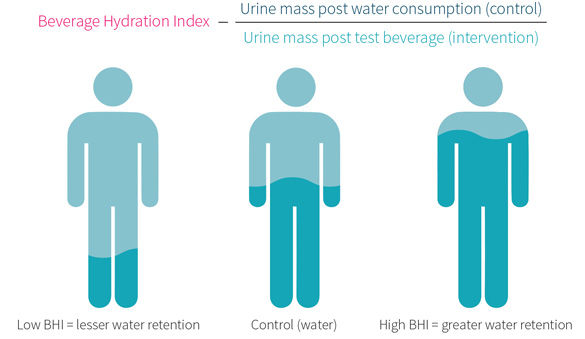

The main outcome measure was the amount of urine passed after ingestion of a given beverage. A beverage hydration index (BHI, as shown in Figure 2) was established by dividing the urine mass after consuming still water by the urine mass for each test beverage. A high BHI means more water is retained in the body than if the drinker had drank an equal volume of still water.

Figure 2: BHI calculation

This study examined the effects of 13 different beverages on urine output in order to establish a beverage hydration index. This index was based on the amount of urine produced after drinking each beverage compared with the amount produced after drinking still water.

What Were the Findings?

Urine output from ingestion of full-fat milk, skim milk and the oral rehydration solution was lower than that from ingestion of still water, translating to a higher hydration index. Interestingly, orange juice showed a statistically significant reduction in urine output between the second and third hour, but was no longer statistically different at the end of the four-hour collection period.

The average differences in cumulative urine output compared with still water were 294 grams for full-fat milk, 339 grams for skimmed milk and 362 grams for the oral rehydration solution, which amounts to an approximately 25 percent decrease in urine output compared to still water.

To establish a beverage hydration index (BHI), still water was used as a control and is thus assigned a value of 1.0. Because the water content of the drinks varied from 88 to 100 percent, the BHI was calculated with and without an adjustment for the amount of water ingested from each drink. These results are shown in Figure 3. Using unadjusted values, a hydration index that was higher than water was observed for full-fat milk (1.50), skim milk (1.58), oral rehydration solution (1.54) and orange juice (1.39). However, after adjustment for water content only full-fat milk (1.32), skim milk (1.44) and oral rehydration solution (1.50) were significantly different from water. None of the beverages tested (including coffee) had a significantly lower hydration index than water.

Figure 3: Am I hydrated? A urine color chart

The electrolyte content of each beverage was also measured. The three drinks that provided the greatest degree of hydration (both types of milk and the rehydration solution) also had the greatest levels of electrolytes (sodium and potassium).

Urine output over four hours was lower after drinking full-fat milk, skim milk or an oral rehydration solution, compared with drinking the same amount of water. There were no differences in urine output after ingestion of cola, diet cola, hot tea, iced tea, coffee, lager, orange juice, sparkling water or sports drink, compared with still water.

What Does the Study Really Tell Us?

This study takes the important first step toward establishing a beverage hydration index, which can be used to compare the short-term hydration potential of different beverages. This can serve a similar purpose as the glycemic index and insulin index: a way to compare how different liquids get processed and absorbed by our bodies. Note that hydration prior to the test was controlled for, so participants were in a euhydrated state. It is possible that there would be some different results in the rehydration potential if participants had been dehydrated, like after exercise or an overnight fast, for example.

The water content of the test beverages ranged from 100 percent (still water) to 88 percent (full-fat milk), but participants consumed exactly one liter of each. This is why the researchers reported the BHI both unadjusted and adjusted for water intake. The adjustment made very little difference: orange juice was on the fence of statistical significance, with only unadjusted values being significantly different from water.

This is the first study to establish an index for short term-hydration. It measured urine output in euhydrated individuals, so applicability to other situations, like after exercise, is unknown.

The Big Picture

Classifying beverages according to their ability to hydrate can serve a number of purposes. Beverages that promote fluid retention may be beneficial in situations where there is limited access to fluids, or when frequent bathroom breaks would be undesirable. The researchers that conducted the study under review are very experienced in the world of hydration research, so it’s appropriate that they are creating a novel BHI.

Fluid absorption is affected by a number of factors, including electrolyte content (mainly sodium and potassium) and glucose content. The BHI can recognize and quantify the effect that these various factors may have on an individual’s hydration status. The results of this study are in line with previous research in the area. The drinks with the highest BHI also had the highest electrolyte content. Acute ingestion of a high-sodium beverage has been shown to result in an increase in total body water. People often associate sports drinks with having a high electrolyte content, but in reality they contain less sodium than milk, and less potassium than seven of the other tested beverages, including tea and coffee, making the total electrolyte content of sports drinks quite low. Previous research has also shown that both milk and milk with added sodium are both effective for rehydration (as measured by cumulative urine output) than either water or a sports drink.

In contrast to the enhancement of fluid absorption by electrolytes are the known diuretic effects of caffeine and alcohol, which act by inhibiting arginine vasopressin (also called anti-diuretic hormone). No effect from the caffeine was observed from any of the drinks in this study, which ranged from 96 to 212 milligrams. A measurable effect on urine output would typically require more than 300 milligrams of caffeine, while the coffee used in this study was reported as having a caffeine content of 212 milligrams per liter. Although this is on the low side for coffee (which would be expected to range from 250 to 1000 milligrams per liter), the researchers performed their own analysis using HPLC to get this value. The alcohol content in one liter of lager beer also did not increase urine output in this study. A previous study looking at fluid balance in response to alcohol in both euhydrated and hypohydrated states found an increased urine output after alcohol ingestion when euhydrated, but no differences when hypohydrated.

While the urine output of each participant was collected for four hours, the BHI values were based on the net fluid balance after two hours. The researchers stated a number of reasons for this decision. The majority (82 percent) of urine output over the four-hour period was collected after two hours, but most people would typically not go longer than two hours without access to fluids, and differences between beverages are evident by two hours. Also, they report that there was very little difference in the calculated BHI whether it was based on the first two hours or the entire four-hour period. With that said, it does seem a bit strange that they would ignore half of their data points, particularly in light of the fact that the original description of the trial states that they would calculate the BHI at each hour over the four hours.

Other considerations with this type of research include gender differences. The diuretic response to a water load can be greater in women than men, suggesting that women turn water over more quickly than men. Determining if the measured BHI values would be the same for women requires further research.

A variety of factors can influence fluid absorption. Electrolyte content is a primary factor, and the presence of electrolytes in beverages such as milk explains their higher hydration index score, even compared to sports drinks that are marketed for hydration purposes. Due to potential sex differences in fluid balance, further research in women would be helpful.

Frequently Asked Questions

Would the results of this study (done over a four-hour window) hold true over a 24-hour time period?

Possibly. A previous study that had participants consume water or various combinations of caffeinated or non-caffeinated beverages (sodas and coffee) found no significant differences on 24-hour hydration status. Neither milk nor an oral rehydration drink was included in that study, however. Additionally, a 2015 study found no differences in 24-hour hydration when consuming various combinations of water, cola and orange juice. It is unclear what the effect of hydrating only with milk or the oral rehydration drink throughout an entire day would be, but that situation is also quite unrealistic.

What effects would protein, fat and carbohydrate content of a drink have on BHI?

Very little fluid absorption takes place in the stomach, so the ingested fluid needs to empty into the small intestine before it can be absorbed. Solutions that include carbohydrates at a concentration of 1 to 4 percent can be absorbed faster, but higher concentrations than that could impair absorption. There are a number of moving parts to this mechanism, however, as evidenced by the fact that there were no differences in BHI for regular or diet cola. It is also known that fat and protein can delay gastric emptying time, and could potentially have an effect on BHI.

Would the temperature of a drink affect BHI?

Not likely, based on the results of this study that showed no differences in BHI between cold and hot tea. Although people often claim that certain temperatures are better for fluid absorption, there are likely no differences.

What Should I Know?

This study established a new method for quantifying the effect of various beverages on hydration. No differences were found compared to water after ingestion of cola, diet cola, hot tea, iced tea, coffee, lager, orange juice, sparkling water or a sports drink. Only full-fat milk, skim milk and an oral rehydration solution led to a reduced urine output after drinking one liter, compared with drinking the same amount of still water. The hydration index established by this study may be useful in situations with limited access to fluids or bathroom breaks.

Reproduced with permission from Examine.com. All rights reserved.

More Articles

- ProSource™: April 2016

Creating Memorable Movement Experiences for Clients and Participants

Health and Fitness Expert

- ProSource™: April 2016

Functional Anatomy Series: The Abdominals

Health and Fitness Expert

- ProSource™: April 2016

Branch Out! 4 Fun and Fresh Circuit-training Formats

Health and Fitness Expert

- ProSource™: April 2016

How to Monitor Participants’ Intensity in Group Fitness Classes

Health and Fitness Expert

- ProSource™: April 2016

Coaching Behavior Change: A Better Way of “Teaching”

Health and Fitness Expert