Reality Check: Are Planks Really the Best Core Exercise?

Not long after working your core became the central focus of fitness training, the plank eclipsed the crunch (which had overtaken the sit-up) as the go-to core exercise. Also known as a front hold, hover or abdominal bridge, the plank is, at least in its basic form, a static, isometric strength exercise that could be called a pre-push-up. It involves maintaining a difficult, potentially arduous, position in which one’s body weight is held up by the hands or forearms, elbows and toes—often for an extended period of time.

The plank became so popular so quickly—and was proven in both the gym and the research lab to deliver the goods—that until recently, very few trainers even bothered to take a second look. However, now that the dust has settled, a few voices are quietly questioning not whether the plank is a quality exercise, but maybe, just maybe, fitness pros may be over-relying on it in core training or not properly integrating it into clients’ overall workout regimens.

How Planks Got So Popular

The plank gained such rapid favor in the fitness community because it did such good job training the abdominals for what the body needs them to do, explains Dr. Glenn Wright, an associate professor of exercise science at the University of Wisconsin, La Crosse. “A lot of strength trainers realized that the main function of the abs is to stop, not start, motion, and the plank came out of what the abs are asked to do—resist the spine from moving, such as when fighting off an opponent, and strengthening the lower back.”

According to Wright, planks work the abs the way they’re supposed to function—isometrically. “They maintain the stability of the core muscles, which support proper posture by safeguarding an erect position and proper alignment of the spine.”Dr. Jinger Gottschall, assistant professor of kinesiology at Penn State University, whose research on the benefits of planks is considered by many to be primary, says that the plank is a superior core exercise to the crunch or sit-up because it provides “more three-dimensional activation, from hip to shoulder, whereas the crunch is an isolated move that hits just your abs.” She adds that planks not only strengthen the core, but also the shoulders and hips—and you can improve your balance if you do variations with your arm or leg.

Wright says that the curl or sit-up goes against the natural curve of the lumbar spine. “When you teach sit-ups, you tell the person to flatten his back to the floor, which alone could cause pain in the lower back—the very condition strengthening your abs is supposed to prevent. Conversely, planks prevent lower-back pain.”

Jennifer Burke, district fitness manager for Crunch in Los Angeles, says that planks serve an additional purpose: “They set you up to be able to do other core exercises in the most efficient and effective way.”

Planks are also pretty safe, argues Dr. Mike Bracko, a sports physiologist, ACSM Fellow and director of the Institute for Hockey Research in Calgary, especially compared to sit-ups. “Planks use neutral spine loading and not trunk flexion—as in sit-ups—to strengthen the abs. If you ask a client with a weakened intervertebral disc to do a sit-up, it can cause that disc to herniate or bulge by pinching it.”

Bracko says that the forceful trunk flexion required by sit-ups and the like is exactly the type that we try to avoid performing in regular daily activities. “More people than ever realize the perils of forcefully bending over at the waist from a standing position.”

Some trainers feel that planks, if anything, are underrated. Burke is one such voice. “A lot of people underrate planks, but if they’re done correctly they induce scapular retraction [the movement of your shoulders up and back], and activate the transverse abdominus, glutes and quads.”

Bracko thinks that not enough trainers introduce planks to their clients or athletes. “Front planks are a great way to work the abs and obliques. Some people complain that you can’t get a ‘six-pack’ look by doing planks. Not only is that false—you can achieve that look if you do planks on one arm and one leg—but it raises the question of your intention. Are you doing core exercises to get a six-pack or to strengthen your core?”

Burke says that any backlash or boredom regarding planks is probably the result of doing them incorrectly. “A lot of people think it’s an easy exercise, so they don’t keep their pelvis in a neutral position; it’s either too high or too low. They also don’t keep their shoulders aligned and retracted, allowing the shoulder blades to wing up, and don’t fully engage the transverse abdominus and glutes at the same time.” How do you know if you’re doing them wrong? “If you’re feeling the brunt in your lower back and arms and not through your abs, glutes and quads,” says Burke.

Are There Better Alternatives to the Plank?

While planks are universally respected in the field of exercise science, some people cite reasons for why there may be better alternatives. Dr. Wayne Westcott, instructor of exercise science at Quincy College and co-author of ACE’s Guide to Youth Strength Training, says, “I'm not against planks, but I feel that they don’t work the abs in the most advantageous way and have multiple drawbacks. To build muscle strength,” Westcott explains, “you need to activate the muscle to near fatigue, within the anaerobic energy system, which typically takes 60 to 90 seconds. Any exercise that takes longer (including planks held beyond that range) doesn’t address muscle strength or size.”

And, because planks are isometric and have limited range, Westcott argues that they don’t provide the universally recommended full range of motion. Plus, “some populations shouldn’t do isometric exercises because they raise blood pressure,” cautions Westcott. “They also put tremendous pressure on your lumbar spine.”

Additionally, another of Westcott’s caveats is that there’s no way to use added resistance while performing a plank, which impedes muscle resistance and potential growth.

Anthony Wall, director of professional education for ACE, has a slightly different take on the value of planks. “One of the reasons for doing planks is that they are a good way to focus on the core without movement—as seen in a push-up. They can be used as part of the stability phase of training, immediately prior to movement, and in a number of ways to increase or decrease the degree of difficulty. For example, they can be done on your elbows and knees, which is much less taxing than doing them on your hands and feet.”

However, while Wall feels that planks occupy an important place in core training, he acknowledges that they can be overused. “If a client cannot stabilize effectively through his core, a plank may not the best exercise for him. And while many people think planks are a boring movement, a good fitness professional can change levels and add movements for variety.”

PLANK ALTERNATIVES

So, in keeping with Wall’s advice to add variety and movement to the basic plank, here are several alternatives worth trying. Hold each exercise for as long as possible while maintaining proper form. If the exercise calls for movement (or reps), do five to 10, unless otherwise specified. Planks—or any of their variations—can be performed two to three times a week, combining them with exercises that work other areas of the core. You can vary the intensity a little or a lot, depending on your choice of exercise. You can also add in different challenges, either by creating instability (with a TRX Suspension Trainer or stability ball, for example), or by adding movement.

Jacks. From a standard plank position, jump your legs out and in.

Mountain climber. Start in standard plank position. Bring the left knee in toward the chest and set the foot on the floor behind the hand. Jump up and switch feet in the air, bringing the right foot up and the left foot back. Continue alternating the feet as quickly as possible for 30 to 60 seconds. (Option: Keep the toes off the ground and simply bring the knees up to the chest.)

Side plank. While the standard plank targets the connection between the lower back and the abdominals, this most common variation targets the obliques and helps stabilize the spine from side to side. Lie down on your side, leaning on one hand or elbow, your chest facing out instead of toward the floor. Make sure your hand or elbow is aligned with your shoulder. And don’t let your hips sink—keep them inline with your head and feet. Lift your hips off the ground and raise the top arm straight up to the sky. Hold the position for up to 30 seconds, then lower the hips back down. To increase the difficulty, lift your top leg as high as possible.

Stability-ball plank. This exercise can be done one of two ways—with the forearms on the ball (and feet on the floor) or the tops of the shins or feet on the ball (and hands or forearms on the floor). Both present a significantly greater balance challenge than the standard plank.

Stir the pot. Kneel on the floor behind a stability ball with your knees hip-width apart. Place your hands on the ball with your palms together. Keep your spine in neutral alignment as you roll the ball away from you until your elbows are on top of the ball. Move your elbows on the ball to simulate stirring a big pot, while maintaining a stable plank. Pull your abs toward your lower back to initiate the return to your starting position. To add more challenge, lift the knees and tuck the toes under to perform the exercise. Note that the size of the circle in your "stirring" motion directly affects the intensity—a larger circle is more challenging. Do five to 10 reps in one direction and repeat in the other direction.

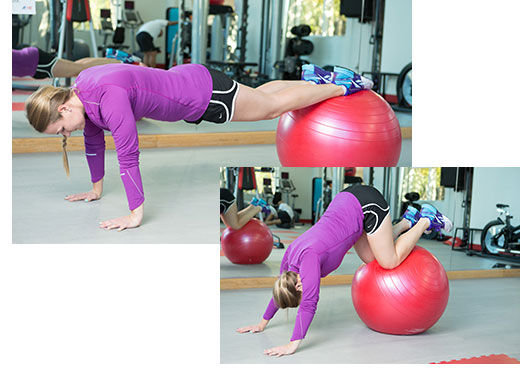

Stability-ball knee tucks. Lie across a stability ball and walk your hands out in front of you until you are in plank position with the ball positioned beneath the shins or ankles. Brace the core and curl the knees in toward the chest. The ball will roll forward as your knees tuck under your torso and your hips lift toward the ceiling. Hold this position for a breath and then extend the legs back to return to plank position. Do 10 to 15 reps, or as many as you can with proper form.

Suspension Trainer knee tucks. This exercise provides the benefits of both a plank and a crunch. Adjust the TRX Suspension Trainer cables so they hang about 12 inches off the ground. Place your feet in the foot cradles, with the tops of your feet facing the ground. Point your toes down toward the floor. Reach your arms out and get into push-up position. Pull your knees into your chest as you bring your hips up slightly into the air. Extend the legs and return to the starting position. Complete the appropriate number of repetitions.

Down-dog Split With Knee Dives. Begin in downward-facing dog. Raise the left leg high up to the sky and then bend the knee and pull it toward the outside of the left shoulder, feeling a pinch in the side body. Straighten the leg back and repeat three to five times. Repeat on the right side. (Optional: Alternate between bringing the knee to the outside shoulder and crossing to the opposite shoulder.)

Beyond Static Planks

Jonathan Ross, ACE Senior Consultant and author of Abs Revealed, has a fresh take on planks. “In first grade, you learn the alphabet, but if all you do is keep studying the alphabet, you never learn to build words; use words to build sentences; use sentences to communicate.” According to Ross, static planks are like the first grade of core training, “and you shouldn’t stay in first grade forever. Life is movement so effective exercise—including core training—should always progress toward movement, not the lack of it.” Stability is the prerequisite for mobility. Static planks beyond 30 seconds are likely not the most effective use of valuable training time. For more helpful tips on how to create an excellent plank and how to add numerous moving progressions, see the ACE Video featuring Ross, Plank School.

More Articles

- ProSource™: February 2014

Upper-body Causes of Back Pain (and How to Fix Them)

Health and Fitness Expert

- ProSource™: February 2014

Strongman Training for Your Clients

Health and Fitness Expert

by

by