Over the past several years, an area of fitness has experienced radical growth, one that might be under the radar of many fitness professionals: endurance sports. You might be surprised to learn, for example, that a staggering 518,000 people finished marathons in 2011, an all-time high for marathon finishers in the U.S. And the number of U.S. marathons with more than 1,000 finishers increased from 45 in 1999 to 94 in 2012. USA Triathlon membership grew to more than half a million in 2012 and, according to the Sports and Fitness Industry Association, almost 2 million people competed in at least one triathlon in 2011.

More and more of our clients are participating in endurance events like marathons and triathlons and, although a few may be competitive in their age group or are working with an outside endurance coach, most are weekend warriors looking for the next challenge. Whatever the case, we need to know how to help our clients lower their risk of injury while also improving performance in their chosen events. And, more often than not, that means helping your clients implement a safe and effective resistance-training program to complement their endurance training.

Who Is an Endurance Athlete?

Anyone who participates in events such as the local 5K, half-marathon or marathon can be considered an endurance athlete. Triathletes training for a sprint all the way up to an Ironman distance event also fall in this group. But what if someone isn’t training for a specific event? If a client regularly participates in repetitive linear cardiovascular training, they will also benefit from this information. This includes general fitness clients who actually enjoy doing their cardiovascular activity on a stationary bike, treadmill, stair climber, or rowing machine and are moving linearly but going nowhere.

Let’s take a look at the science behind the benefits of resistance training and how you can use this information to help your clients.

So why resistance training? We all know that resistance training has positive health benefits for the general population, but why is it important for endurance athletes? According to a study published in the Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science (Aagaard and Andersen, 2010), endurance-trained athletes who added strength training to their programs improved their endurance capacity by increasing type 2 fibers. They also made substantial gains in maximal strength, force production and neuromuscular function. Similarly, a literature review by Laursen, Chiswell and Callaghan (2005) showed that resistance training contributed to a 12 percent increase in lactate threshold without a change in VO2max in endurance-trained athletes. They also saw improvements in performance through better economy of motion, which can be attributed to neuromuscular adaptations. Researchers also found no evidence that resistance training has a negative influence on endurance performance.

As many strength and conditioning coaches, personal trainers and group fitness instructors know, explosive resistance training is an effective method of improving performance in endurance sports. This is backed by research by Mikkola and colleagues (2007), whose study demonstrated that specific explosive-type strength training leads primarily to neural adaptations (e.g., increased rate of neural activation of motor units) rather than to muscular hypertrophy. This is beneficial in endurance sports, as athletes need to transport their body mass over long durations while experiencing high levels of impact.

From an injury-prevention perspective, a wide scope of research and anecdotal evidence has demonstrated a link between dysfunctional hip musculature and running injuries, specifically in female cross-country runners. And, of course, the general health benefits of resistance training are significant, and include improved bone density, metabolism, body composition, and muscle and connective-tissue strength (American Council on Exercise, 2014).

Programming Considerations

Now that you have enough evidence to convince your endurance-focused clients of the benefits of strength training, let’s look at how to begin programming for them by using the ACE Integrated Fitness Training® (ACE IFT®) Model. The remainder of this article focuses on using the functional movement and resistance-training component to choose appropriate exercises and effective programs for your clients who want to improve endurance-related performance.

For endurance athletes, resistance training should supplement an athlete’s training regimen—not detract from it or make them more tired and sore. It is important to build slowly from one phase of training to the next to avoid injuries, which is why using the ACE IFT Model is essential. Keep in mind, however, that some athletes may feel that they are ready to be doing loaded movements and exercises that increase power and agility, which are featured in phases 3 and 4 of the functional movement and resistance-training component. After an initial consultation or assessment, you will likely find that your client has muscular imbalances and/or movement compensations that need to be addressed. Your job as a fitness professional is to understand how to regress the client using the ACE IFT Model (or refer your client out, if necessary). It is also important to also keep exercises from phases 1 and 2 in the training program as part of a dynamic warm-up to maintain muscle balance, flexibility and mobility/stability for all clients, regardless of fitness level or exercise goals.

Before getting started, here are a few things to be aware to ensure the resistance-training programs you design are both safe and effective for your endurance-trained clients.

Client History

Be sure you know your clients’ past injuries and other medical history (this can be obtained through a PAR-Q and/or a health-history questionnaire). To be able to design a training program that your clients will actually enjoy, be sure to discuss their likes and dislikes when it comes to exercise. Also, upon completing an initial movement screen or postural assessment, take note of your client’s physical strengths and weaknesses as they relate to movement.

High-impact Training

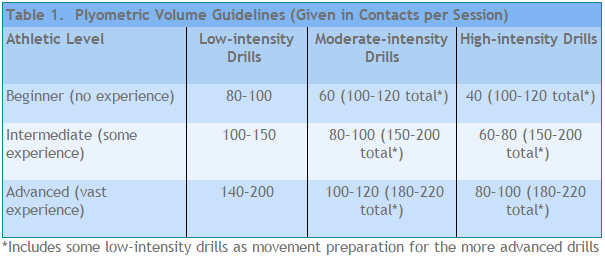

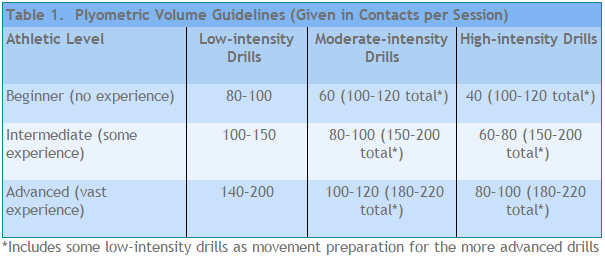

When not programmed appropriately, high-impact exercises such as plyometrics can cause injury rather than provide benefits. Although high-impact moves have shown to be highly effective in improving performance, keep in mind this Latin proverb: “What nourishes me also destroys me.” In other words, you can have too much of a good thing. Table 1 indicates the number of contacts per session that are considered safe for different levels of athletes (beginner through advanced).

Linear Movement

Endurance sports largely focus on repetitive linear activity. Therefore, the muscles that provide lateral and/or rotational movement may become weak. Over time, this will create imbalances in the body and may cause injury.

Building and maintaining both stability and mobility is important for all clients, and especially for endurance athletes. A client’s choice of endurance sport determines whether stability or mobility should be emphasized (although both should be regularly included in every program). For example, rowing is a simultaneous type of endurance sport, meaning that both sides of the body are doing the same thing at the same time. For rowers, stability is important to maintain as the body will be moving without a lot of variation in joint range of motion. On the other hand, sequential endurance sports such as running, cycling or cross-country skiing, where one side of the body moves followed by the other side (with the upper- and lower-body moving in opposition), require higher levels of mobility to allow for adequate rotation between the right and left sides of the body (USA Triathlon, 2012).

Range of Motion

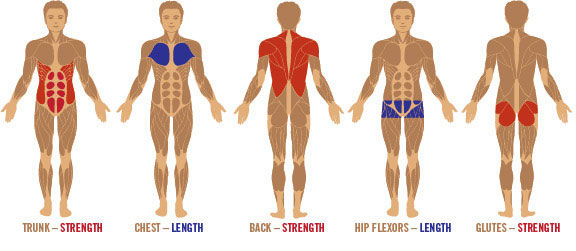

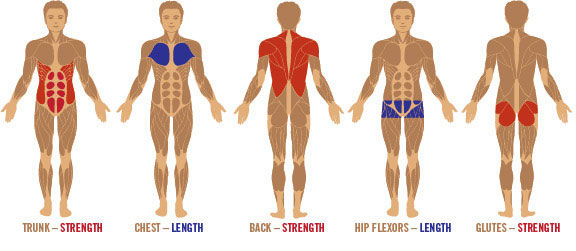

Understanding the length-tension relationship is key when programing resistance training for endurance athletes. If you do not already participate in your client’s sport of choice, take the time to understand the biomechanics of it and how much range of motion is required during the activity. For example, when cycling, the body is in a constant state of hip flexion, which means the resistance-training program should include movements that lengthen the hip flexors while also strengthening the quads and glutes for greater power during the pedal stroke and recovery. Similarly, hip flexors that are too tight may lead to decreased power in the glutes, which leads to an incorrect length-tension relationship and can cause to the hamstrings to do more work than they should. This is called synergistic dominance (USA Triathlon, 2012).

Multiplanar Movements

Be sure to incorporate multiplanar movements into the training plan to improve balance, enhance stability and mobility, and prevent injury. This includes using the five functional movements as outlined in phase 2 of the functional movement and resistance-training component of the ACE IFT Model: bend and lift, single leg, pull, push and rotation. Incorporating these types of movements throughout the program helps ensure that clients are working through primary movement patterns that are essential for both their sports and activities of daily living (ACE, 2014).

Force and Recovery

It is important that you understand the movements that your clients perform most and what muscles create these movements and return them to their starting positions. For example, in running, the glutes and quads are used for hip and knee extension, and the hip flexors and hamstrings are used for both hip and knee flexion. During swimming, the latisimus dorsi are responsible for propulsion during the pull phase of the stroke and the deltoids are responsible for the recovery and for returning the arm to the starting point of the stroke. In cycling, the power phase of the pedal stroke utilizes the quadriceps and glutes and the hamstrings should be utilized to return the foot to the top of the pedal stroke (USA Triathlon, 2012).

Speed

Think about how quickly your clients need to move in their sports. With endurance sports, athletic speed, agility and quickness are not usually areas of focus. However, velocity-building exercises such as power cleans or hang cleans can be used specifically for rapid hip flexion and extension, which is essential to developing a quick finish at the end of a running event or a strong kick for swimming (USA Triathlon, 2012).

Areas of Emphasis

For linear athletes who run, swim, bike, row or ski, several areas of the body should be focused on from both a length and strength perspective. These include:

Program Design

When programing resistance-training sessions for the endurance athlete, break each workout into three areas: warm-up, main session and cool-down.

Warm-up

The warm-up for an endurance athlete should include three elements:

1. Self-myofascial Release (5 minutes). Using tools such as tennis balls and foam rollers over the major muscles groups (e.g., back, quads, calves) that will be used during the session allows the soft tissues to become more pliable and prepared for movement.

2. Stability/Mobility Exercises (5 minutes). Performing exercises that emphasize stability and mobility prior to the dynamic warm-up and training session helps to prepare the proper muscles to become active and protects the moving joints during the main portion of the workout. Examples include glute bridges, supermans and prone shoulder stabilization series.

3. Dynamic Flexibility Movements (5 minutes). These exercises emphasize lengthening the muscle, but without static stretching. Movements like walking lunges to gently lengthen the hip flexors, downward facing dog to open the chest and shoulder joints, and body-weight squats to warm-up the hips are all options for the dynamic flexibility component.

Main Session (~20 minutes)

This part of the workout for an endurance athlete should build muscular endurance, strength and power, while also challenging the cardiovascular system as a method of cross training. Circuit-style workouts tend to work very well and are time-management friendly. Select six to eight exercises that take into account the aforementioned information and separate them into two circuits. Perform both circuits two to three times through, moving quickly from one exercise to the next, with a short break between each round.

Here are two sample circuits:

Circuit #1: Perform each exercise for 30 to 60 seconds, transitioning quickly from one exercise to the next. Rest for 60 seconds before repeating the circuit for two to three rounds.

Overhead Squat

Romanian Deadlift With Upright Row

Hay Baler

Triceps Push-up

Circuit #2: Perform each exercise for 30 to 60 seconds, transitioning quickly from one exercise to the next. Rest for 30 seconds before repeating the circuit for two to three rounds.

Skaters

Pull-ups

Single-leg Split Squat

Thread-the-needle Plank

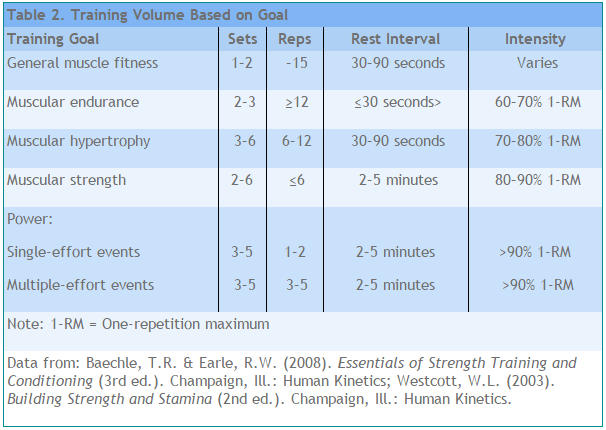

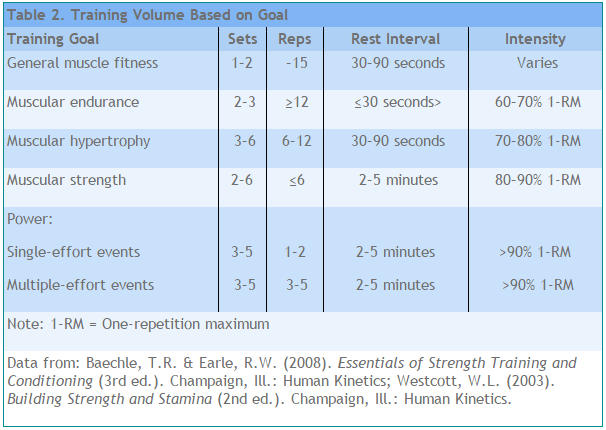

For clients who want to improve overall muscular endurance, choosing the appropriate number of sets and reps, as well as ideal recovery, is essential for helping them achieve their goals (see Table 2).

Cool-down (10 minutes)

Do not allow your allow your clients to skip the cool-down portion of their workouts. Performing static stretches (holding for at least 30 seconds) on the muscles just worked as well as a few dynamic flexibility movements to reduce the heart rate are important aspects of recovery, not only for the workout they just completed, but to prepare for subsequent workouts as well.

The cool-down is also the best time to do more self-myofascial release therapy using a foam roller, and to pay a bit more attention to any areas of concern by providing more specific pressure to the areas of the body that may be bound up (trigger point). Trigger-point therapy is great to do at the conclusion of a workout because the muscles are warm and open to more manipulation.

By implementing the appropriate set/rep scheme and movements that are suitable for the endurance athlete, you can help this exciting—and generally quite dedicated—group of clients achieve their performance goals, reduce injuries and cross the finish line in record times.

References

Aagaard, P. et al. (2011). Effects of resistance training on endurance capacity and muscle fiber composition in young top-level cyclists. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, 21, 6, 298-308.

Aagaard, P. and Andersen, J.L. (2010). Effects of strength training on endurance capacity in top-level endurance athletes. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, Supplement 2, 20, 39-48.

American Council on Exercise (2014). ACE Personal Trainer Manual (5th ed.). San Diego, Calif.: American Council on Exercise.

Brumitt, Jason. (2009). Injury prevention for high school female cross-country athletes. Athletic Therapy Today, 14, 4, 8-13.

Laursen, P., Chiswell, S. and Callaghan, J. (2005). Should endurance athletes supplement their training program with resistance training to improve performance? Strength and Conditioning Journal, 27, 5, 50-56.

Mikkola, J., et al. (2007). Concurrent endurance and explosive type strength training increases activation and fast force production of leg extensor muscles in endurance athletes. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 21, 2, 613-621.

USA Triathlon (2012). Complete Triathlon Guide. Champaign, Ill.: Human Kinetics.

by

by