In early 2011, my wife, Linda, was diagnosed with what we hoped was stage I breast cancer. When she went in for the lumpectomy to remove a small tumor in her left breast, we had reason to be hopeful that this would be her one and only surgery. Unfortunately, the surgeon found a second mass that had to be removed and then did a biopsy of the sentinel lymph node under her left arm and found cancerous cells. The decision was made to remove a cluster of 20 or more lymph nodes from the area. This discovery meant that Linda actually had stage II breast cancer and would need chemotherapy and radiation after all.

[Spoiler alert: She’s doing great!]

Weeks after completing six rounds of aggressive chemotherapy, Linda underwent “mapping” prior to her first round of radiation, which revealed another cancerous tumor, this one in her right breast. Bilateral mastectomy. Recovery. A battle with depression that delayed the start of radiation. Thirty radiation treatments. Recovery. Reconstructive surgery. Hysterectomy. Oophorectomy. Recovery, recovery, recovery.

And somewhere in there—it was so insignificant that neither of us can remember quite when it happened—Linda was told she had lymphedema in her left arm.

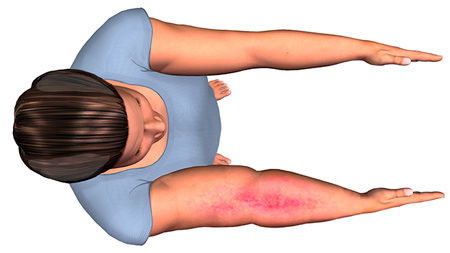

Lymphedema involves a build-up of lymphatic fluid that causes swelling (edema) in either the arms or legs. It can be caused, as it was in Linda’s case, by the removal of lymph nodes, the normal function of which is to trap bacteria, viruses and other substances in the body. In the absence of the lymph nodes, that lymphatic fluid has nowhere to go and pools in the affected limb.

After everything Linda went through, the talk of lymphedema was the final straw. If I may quote her here: “I’m not wearing a [bleep]ing compression sleeve every day! I’ve been through enough.”

It’s certainly understandable that most cancer patients are more than a little overwhelmed. For that reason, it seems that lymphedema and its impact on a person’s life are often downplayed in the aftermath of a cancer diagnosis. That’s a real shame, as it’s a manageable—and in some cases preventable—condition.

Lymphedema 101

Lymphedema refers to swelling in one or more limbs. It is typically caused by the removal or damage to lymph nodes as part of cancer treatment. Other possible causes include the chemotherapy drug tamoxifen and radiation therapy.

There is no cure, but the condition can be managed through the performance of specific exercises that encourage lymph drainage. Compression garments are commonly prescribed by an oncologist or lymphedema specialist, though the swelling must be brought under control first through wrapping of the arm or leg by a physical therapist who specializes in lymphedema treatment. This therapist will likely also perform a very superficial massage technique called manual lymph drainage. All of these treatments are designed to push fluid out of the affected limb and past the area where lymph nodes have been removed or damaged.

Upper-limb lymphedema often occurs in breast cancer patients whose disease has spread to the lymph nodes in the underarms. Lymphedema in the legs may occur after surgery for uterine cancer, prostate cancer, lymphoma or melanoma.

The Role of the Health and

Fitness Professional

When talking about the role of exercise in managing or preventing lymphedema, we’re really discussing two distinct populations: those who have been diagnosed with the condition and those at risk for developing it. Stated simply, anyone who has had lymph nodes removed or undergone radiation therapy as part of their care is at risk. For some, lymphedema reveals itself quickly and a diagnosis is made. For others, lymphedema can develop months or even years later, and the risk doesn’t decrease over time.

“For this reason, prevention is a huge issue,” says Andrea Leonard, Cancer Exercise Specialist, Breast Cancer Recovery BOSU Specialist, and founder and president of the Cancer Exercise Training Institute. “When first working with clients who are cancer survivors, but have not been diagnosed with lymphedema, asking whether they had any lymph nodes removed (and if so, how many) is absolutely essential. Trainers and coaches should also ask clients whether radiation was part of their cancer treatment, as radiation doubles the risk of lymphedema.”

If the answer to both of those questions is “no,” then you can eliminate any concerns about lymphedema. If the answer is “yes” to either one, you can let the client know that eating well and staying active are key elements of lymphedema prevention, and that you are able to help in a number of ways.

Among the things that increase a person’s risk of developing lymphedema are an increase in body-fat percentage and poor nutrition. These two elements are clearly linked, and both are in the wheelhouse of any health and fitness professional. Adipose tissue (i.e., body fat) interferes with the movement of lymphatic fluid in the body, so reducing a client’s body-fat percentage through exercise and proper nutrition is essential.

Leonard offers the following list of precautions that a person with, or at risk for, lymphedema should consider. Many of these are related to the need to do everything one can to prevent infection in the affected limb. If the lymphatic system is compromised in any way (and the removal of lymph nodes certainly compromises the system), then the body has a reduced capacity to fight infection. In fact, lymphedema and infection have a circular relationship, in that each increases the risk for the other.

- Avoid insect bites, burns, skin irritants, hangnails and torn cuticles.

- If scratched, wash and clean the area with soap and water, use antiseptic and cover the scratch to prevent infection.

- Avoid tight-fitting jewelry on the affected area.

- Don’t receive shots, have blood drawn or have blood pressure taken on the affected area. If a client has lymphedema and will be undergoing additional surgeries, it’s essential that he or she mark the affected limb so that no mistakes are made after the anesthesia kicks in.

- Losing weight can help reduce swelling by reducing the amount of fatty tissue, which retains fluid.

- Avoid saunas, whirlpools, steam rooms and hot baths.

- Wear loose-fitting clothes on the affected area.

- Wear compression garments when flying or when traveling to higher elevations.

“Health coaches and personal trainers must never overstep and attempt to perform the role of the certified lymphedema specialist,” says Cedric X. Bryant, Ph.D., Chief Science Officer for the American Council on Exercise. “This includes never performing any type of massage on a client who has, or is at risk for, lymphedema. The last thing you want to do is accidentally push fluid back into the affected limb.”

*For more on “Scope of Practice Concerns,” see the shaded box.

Exercise-specific Precautions for Clients With Lymphedema

Several research studies have found that a program of gradually increasing exercise is not likely to increase the risk of lymphedema. In fact, exercise may actually play a preventive role (BreastCancer.org).

The Physical Activity and Lymphedema (PAL) Trial involved 154 women at risk for lymphedema following breast cancer treatment. The women were assigned to either a “no exercise” group or a group that performed a program of slowly progressive weight training. The researchers found that the incidence of lymphedema was more than three times higher in the “no exercise” group (Schmitz et al., 2009).

This research also included a study of 141 breast cancer survivors who had stable lymphedema. Again, these women were assigned to a “no exercise” group or a group that performed slowly progressive weight training. In this case, the former group saw more than twice as many flare-ups as the latter group, and the women in the weight-training group were not at a higher risk of developing swelling in the arm (Schmitz et al., 2009).

All of that said, there are some exercise-specific precautions that all health and fitness professionals must adhere to when working with a client with lymphedema.

All workouts must begin with an extended, slow and very gradual warm-up. See the shaded box on “Lymph Drainage Exercises” for a series of exercises that clients with lymphedema should perform before every workout.

Progression should be made very slowly when exercising with the affected limb. Begin by moving the limb through a full range of motion. Many clients with lymphedema may find simply moving the limb to be tremendously difficult.

Linda’s situation provides an excellent example of the many complications that must be considered: By the time Linda was cleared to exercise by her oncologist, she had undergone a lumpectomy on her left breast, and then a mastectomy that included the removal of a portion of her latissimus dorsi, which was used to form the chest wall. She had a lot of scar tissue under her left arm, across her chest and in her upper back. The arm itself was swollen to more than 150% of its original size. Lifting the arm overhead was simply impossible.

Now, imagine that scenario in the lower limbs, which are weight bearing during movements of daily living. The potential complications are significant. The ability to move through a full range of motion must be developed before adding any kind of external resistance. Focus on range of motion, then the number of repetitions, then added weight. “A client with lymphedema should never be allowed to lift any kind of weight with the affected limb during the initial sessions,” says Leonard.

Leonard claims that the need for slow progression cannot be overstated. “Remember,” she says, “the client has no idea what his or her body is capable of or can tolerate after battling cancer.” Many cancer patients have balance and cognition issues following chemotherapy, for example, so never assume that you know a client’s capabilities, even if you worked with him or her prior to the diagnosis.

After every workout—especially in the early going—have the client monitor the affected limb or limbs for signs of swelling or redness for 24 to 48 hours. If a client is at risk for, but has not been diagnosed with, lymphedema, the smallest sign of swelling should trigger a trip to the doctor. The earlier a lymphedema diagnosis is made, the easier the condition is to manage.

Never wrap a band or other piece of equipment around the affected limb. Doing so can cause fluid to pool in the hand or foot. Be sure to use equipment with handles instead.

If the client has a compression sleeve, which would have been prescribed by his or her oncologist or lymphedema therapist, it must be worn at all times during exercise, as moving the limb can cause fluid to pool. Note that if a fitness facility is aware that a client has lymphedema and does not require him or her to wear the compression garment, this may be considered gross negligence in a court of law.

Make sure the client is well hydrated and stays cool. If exercising indoors, ensure there is air conditioning or a fan available, as well as plenty of water. If exercising outdoors, avoid the hottest parts of the day. Also, make sure the client is not wearing any tight-fitting clothing, including sports bras or bicycle shorts.

Finally, there are certain activities that are considered too risky for individuals with lymphedema. Repetitive motion with an affected limb can cause the lymph fluid to pool in the hand or foot. For the upper extremities, such activities include tennis, racquetball, golf and bowling. For the lower extremities, these include soccer, skating, running and biking.

Scope of Practice Concerns

Working with clients with lymphedema, who in many cases are recent cancer patients, requires you to function as part of a larger care team. For this reason, you must remain hyper-aware of the limits of your role on that team. As Linda’s story illustrates, there are often a number of factors at play in a person’s treatment and recovery.

“Health coaches and personal trainers must never overstep and attempt to perform the role of the certified lymphedema specialist,” says Cedric X. Bryant, Ph.D., Chief Science Officer for the American Council on Exercise. “This includes never performing any type of massage on a client who has, or is at risk for, lymphedema. The last thing you want to do is accidentally push fluid back into the affected limb.”

Similarly, never offer to wrap or re-wrap a client’s arm or leg before or during a workout. There is a very specific technique involved that must be practiced extensively to be perfected.

It is a great idea to seek out continuing education on the topics of cancer and lymphedema before working with these clients. That way, you will know how to best serve as a resource for your clients and direct them to the correct team member should issues arise. Recommendations and limitations will be outlined by the client’s oncologist and, in most cases, a certified lymphedema specialist. The health and fitness professional must adhere to these recommendations without fail.

Finally, seek medical clearance and direction from the care team before working with any client who has, or who is at risk for, lymphedema.

In Conclusion

The role of the health and fitness professional working with clients with, or at risk for developing, lymphedema is often that of educator. If a client has been diagnosed with lymphedema, he or she may have little or no knowledge of the condition and how it may be treated with a properly constructed exercise program.

Individuals who have regained much of their strength after a cancer battle may re-enter the gym full of vim and vigor—and unaware that they are at risk of developing lymphedema due to the nature of their cancer treatment. In that case, your role is to educate them without overwhelming or terrifying them.

Linda’s story demonstrates the multifaceted and individualized nature of cancer treatment and recovery. Be sure to ask a lot of questions during early sessions and educate yourself on the specifics of each client’s situation.

Once you understand the modifications and restrictions of an exercise program for each client, you will see that the treatment or prevention of lymphedema relies upon the very skill set that you already have—teaching clients to alter their lifestyles in a way that improves their body composition and sets them up for better overall health.

Andrea Leonard teaches clients with lymphedema to perform the following sequence of movements as part of the warm-up to prepare the body for exercise. The idea is to provide an avenue for the lymph fluid to travel as it leaves the affected limb prior to a workout. For example, the pelvic tilts and modified sit-ups that start each series will push fluid from the lymph nodes in the groin, creating space for otherwise trapped fluid to enter.

Lymph Drainage Series for the Upper Body

- Pelvic tilt

- Modified Sit-up

- Neck stretches

- Shoulder shrugs

- Shoulder rolls

- Isometric shoulder blade squeeze

- Isometric chest press

- Shoulder circles

- Wrist circles

- Wrist flexion/extension

- Fist clench

Lymph Drainage Series for the Lower Body

- Pelvic tilt

- Modified sit-up

- Bicycles

- Leg circles

- Knee flexion/extension

- Plantar flexion/dorsiflexion

- Foot circles

Further Your Knowledge

It takes a special, compassionate person to work with cancer patients—and requires a deep understanding of exercise oncology—but it is one of the most rewarding opportunities you will have in your career. Learn more about the new Cancer Exercise Specialist program, which will give you the tools and confidence that you need to work safely and effectively with cancer patients and survivors.

Cancer Exercise Training Institute Cancer Exercise Specialist

Guide patients through treatment into recovery and long-term survivorship.

References

BreastCancer.org (2017). Lymphedema and Exercise. www.breastcancer.org/treatment/lymphedema/exercise

Schmitz, K.H. et al. (2009). Physical Activity and Lymphedema (The PAL Trial): Assessing the safety of progressive strength training in breast cancer survivors. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 30, 3, 233–245.

by

by