Do you have clients who seem to follow every exercise trend? You’ve watched them switch from kickboxing to indoor cycling to yoga to Pilates to Zumba to CrossFit and back to indoor cycling. And that doesn’t even take into account all of the late-night TV fitness products they probably have laying around in the garage or the back of a closet. These “program hoppers” are easily distracted, so they’re always looking for the newest, latest greatest fad that promises quick results. It’s well-established that for an exercise routine to be effective it needs to be performed consistently for a period of time. Changing exercise programs too frequently does not allow the body to adapt to the physical stimuli and could reduce the chance of experiencing the desired results. This leads to two important questions:

- Is changing exercise programs or methods too frequently effective or ineffective?

- How can a personal trainer help a program hopper find an exercise program that will keep him or her engaged long enough to experience results?

Program hoppers are at least making an effort to exercise and, or course, any exercise provides benefits. But changing programs too often or doing different types of exercise at the same time may not help these individuals achieve the results they desire. If you see this program-hopping trait in some of your clients, the first thing to do is to determine what exactly is he or she is looking to achieve with an exercise program. If a client’s goal is to increase muscle mass for a lean, sculpted appearance (a strength-based goal), this is best achieved with resistance training. If a client’s goal is to improve cardiorespiratory fitness for activities like running or cycling, a focused approach to develop activity-specific endurance would be most appropriate.

Basic Principles of Exercise Program Design

Exercise is physical stress applied to the body. Repeated applications of exercise stress causes physiological adaptations so the body can become more effective at handling and overcoming these stresses. The SAID Principle (Specific Adaptations to Imposed Demands), which is one of the foundational principles of exercise, states that the body adapts to the specific physiological demands imposed by the exercise program. The other two basic principles of exercise program design—progression and overload—dictate that to be effective, exercise needs to challenge the body to work harder by gradually increasing intensity or complexity of the applied stimulus (Baechle and Earle 2008).

According to these principles, if the goal of exercise is to improve aerobic endurance, progressively increasing the intensity or volume of metabolic stress using cardiorespiratory exercise is the most effective way to achieve that goal. Metabolic conditioning helps the body become more efficient at converting carbohydrates and fats into energy, with or without the presence of oxygen. If the goal is to increase strength, add lean muscle or enhance muscular definition, the focus needs to be on a progressive mechanical overload. A mechanical overload of resistance training recruits more motor units and their attached muscle fibers, while gradually increasing their size and ability to generate force when contracting. It’s important to note that to ensure optimal adaptations to exercise, you must avoid applying too much metabolic or mechanical stress too quickly. Mechanical and metabolic overloads are not mutually exclusive; cardiorespiratory exercise provides some mechanical stimulus to the involved muscle fibers, while resistance training increases the demand on the body’s metabolism to provide energy for muscle contractions. As a personal trainer, you need to know how much of each to apply, and when, to help your clients achieve their desired results.

Metabolic and mechanical overloads applied to the body simultaneously during a workout is referred to in the research literature as concurrent training. Concurrent training has been shown to provide overall fitness benefits and can actually enhance an individual’s aerobic capacity. It does, however, limit the effectiveness of improving muscular strength. In a review of the literature on concurrent training, Wilson et al. found that combining resistance training with running for endurance can result in losses to both the strength and hypertrophy related to enhanced muscular definition (Wilson et al., 2012). This is important information you can use to help program-hopping clients identify the type of training that will best provide the results they seek.

Exercise Programs for Results

The late Dr. Mel C. Siff described exercise as “a problem-solving task to perform a movement in the most efficient manner possible” (Siff and Verkoshansky 2009). The application of this theory means that a client’s desire for results becomes the “problem” that the exercise program is attempting to solve. When working with a program hopper it’s important to explain the need for a specific training goal because exercising to “lose weight and tone up” is too vague and doesn’t provide much direction for a workout program. Once a client defines a specific, measurable, attainable and realistic goal, your job as a trainer is to work backwards to develop a program with a gradual progression of exercise intensity to achieve the goal.

Designing an exercise program that applies the SAID, overload and progression principles is the most effective way to help a client. This approach, however, requires six to 12 weeks or longer of progressively challenging training intensity before the exercise program delivers lasting results. If you’re working with a program hopper, the challenge is further complicated by the fact that you likely have a client who wants results, but lacks the ability to commit to a program for the length of time it might take to create the physiological changes desired. When asked how he works with individuals who are always looking for the next ‘big thing’ in fitness, Jonathan Ross, 2006 ACE Personal Trainer of the Year, explained that he works to educate clients about the benefits of consistency. “If you bring enough consistency and the right intensity to the workout, almost any program can get results, especially for [individuals] with modest fitness goals.”

Exercise is based on movement, and movement is a skill that must be properly developed. When it comes to exercise, some variability and change is good and keeps the workouts engaging and interesting. However, changing the exercises too frequently does not allow the neuromuscular system to learn the movements or, more importantly, develop the skill to master them as a subconscious reflex. The best way to help clients learn exercise movement patterns and develop the skill to be able to execute them at a subconscious, reflexive level requires an appropriate progression of the three stages of motor learning (Schmidt and Wrisberg 2004). These are:

Verbal-Cognitive

The initial phase of learning requiring conscious thought of movement. In this stage, clients gain information and understanding of the exercise movement through kinesthetic, visual and auditory senses. It is important to provide the proper verbal instructions, visual demonstrations and specific feedback to help facilitate the learning process.

Motor

The second phase where clients are develop an understanding of how individual parts of the movement relate to one another. Movements become more efficient, but errors still exist as the client is learning how to self-correct any deviations from the optimal path of motion. In this phase of learning, quality practice produces refinement of the learned skill. As clients learn the movement, the trainer provides minimal feedback to help the individual refine his or her skills.

Autonomous

The final phase when the movement becomes automatic, efficient and somewhat effortless. The goal of teaching any exercise or movement is for it to become a reflex so the client does not have to think about what he or she is doing during the movement. As a result, the client can increase the challenge by adding intensity (heavier load) or increasing volume (more repetitions). Your job during the learning process is to provide the guidance and feedback to ensure optimal motor learning and automation. Once a client has reached this phase, it is up to you to determine how to safely increase the intensity or volume to help the client to continue to experience results.

So, the answer to whether or not changing exercise programs or methods too frequently is effective or ineffective is that it is overwhelmingly ineffective. Consistency in exercise selection allows clients to develop and enhance their motor skills related to the movement tasks required by the workout program. Many people might think that constantly changing workouts will keep challenging their bodies (which it can), but the frequent changes mean that the body does not have the opportunity to learn and improve upon its existing movement skill. We can compare exercise to studying for a language—if you study Mandarin one semester and then Farsi the next semester, you won’t be able to learn either very well. Mastering the ability to speak a language requires constant learning and refinement of proper pronunciation, tonality and grammar skills, which doesn’t happen in a short period of time.

Just like learning a language requires knowing the fundamentals before becoming fluent, maintaining consistency of exercise selection can help clients experience continuous improvement. This, in turn, helps them develop greater levels of self-efficacy, which can lead to better long-term results. In addition, mastering the foundational movement skills involved is essential before increasing the intensity or challenge of an exercise. Changing exercise programs frequently before an individual has a chance to automate the involved movements means the client won’t be able to progress the intensity to the highest level he or she might be capable of achieving. “When jumping around, you are not necessarily allowing yourself to fully adapt to any one modality,” ACE Senior Consultant and owner of Movement First in New York City Chris McGrath tells his clients. “This makes ‘mastering’ a single modality unlikely, which ultimately interferes with maximizing results.”

Just like learning a language requires knowing the fundamentals before becoming fluent, maintaining consistency of exercise selection can help clients experience continuous improvement. This, in turn, helps them develop greater levels of self-efficacy, which can lead to better long-term results. In addition, mastering the foundational movement skills involved is essential before increasing the intensity or challenge of an exercise. Changing exercise programs frequently before an individual has a chance to automate the involved movements means the client won’t be able to progress the intensity to the highest level he or she might be capable of achieving. “When jumping around, you are not necessarily allowing yourself to fully adapt to any one modality,” ACE Senior Consultant and owner of Movement First in New York City Chris McGrath tells his clients. “This makes ‘mastering’ a single modality unlikely, which ultimately interferes with maximizing results.”

The Science and Art of Exercise Program Design

So, returning to second question we posed earlier, if program hopping is not an effective way for your clients to meet their goals, how can you help them find an exercise program that will keep them engaged long enough to experience results? Answering this question is a little more complicated. If there is a not a specific goal other than to be healthy and have fun with exercise, then changing programs frequently is not necessarily a bad thing. However, the changes should be applied in a way that is consistent with what the research tells us about how the body adapts to exercise. This is where the science of exercise program design merges with the art of how to successfully engage your client and help them find enjoyment in physical activity.

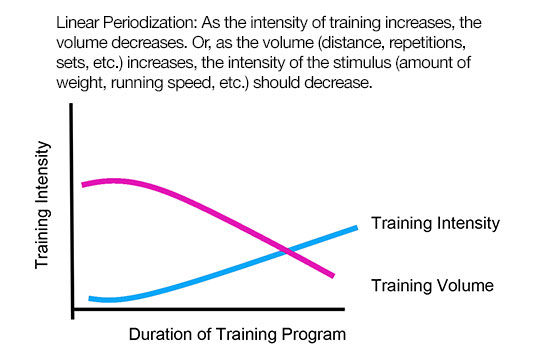

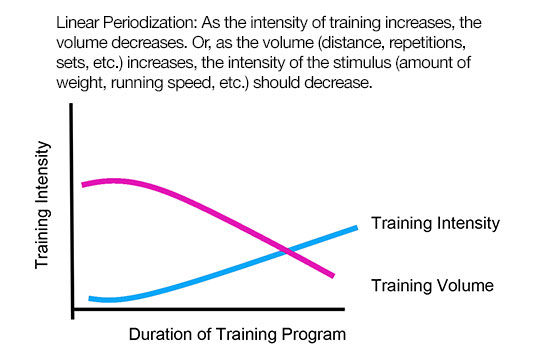

Traditional periodization models apply a gradual, linearly increasing training intensity, with workouts becoming progressively challenging over a period of weeks or months (Figure 1). In linear periodization models, as exercise intensity increases, the amount of work, or volume (the number of repetitions and set performed), should decrease to allow for optimal recovery and adaptation. Rest periods with minimal activity, referred to as active rest, are essential to allow for recovery from the stress of exercise and optimal adaptation to the training stimulus. Exercising at a high intensity or volume for too long or too frequently could lead to overuse injuries or overtraining, both of which can be major impediments for achieving desired results. By starting with lower-intensity exercises before progressing to more challenging workouts, the application of linear periodization can help some clients stick with their programs. Likewise, using linear periodization to gradually increase intensity or volume can be an effective way to train for a specific athletic competition, but it might not provide the stimulus or change a program hopper needs to stay engaged.

Figure 1: An Example of Linear Periodization

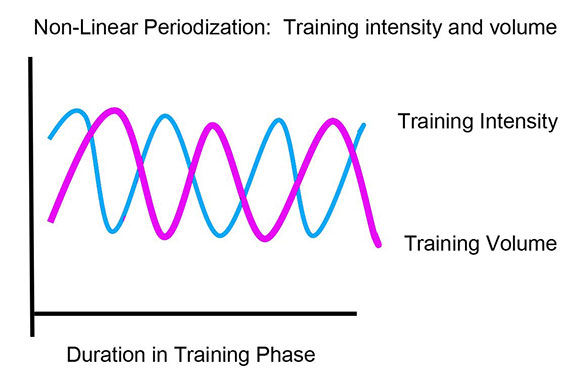

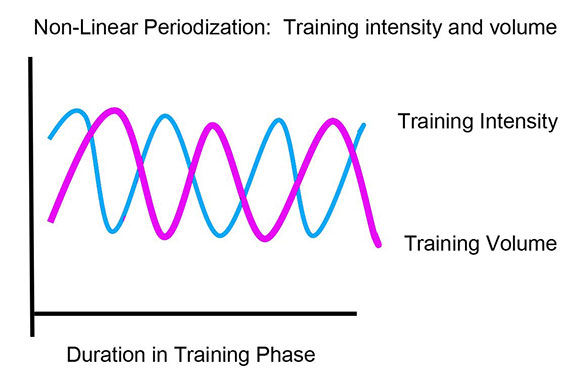

Instead, one of the best options for applying exercise science to engage program hoppers is to follow a model of non-linear, undulating periodization, in which workout intensity and volume change on a much more frequent basis, either from day-to-day or week-to-week (Figure 2). Non-linear, undulating periodization models maintain consistency of exercise movements, which allows for optimal motor learning, but constantly alternate volume and intensity between high, moderate and low. The benefit is that the body develops the skill to execute the movements reflexively, but is constantly challenged with frequently changing intensity. Constantly changing the exercise stimulus while maintaining consistency in the mode or type of exercise volume and intensity can help program hoppers stay engaged. When designing a program based on undulating periodization, remember to allow at least 48 hours between high-intensity training sessions for optimal protein re-synthesis, muscle glycogen replenishment and recovery from neuromuscular fatigue.

Figure 2: Non-Linear Periodization

Training intensity and volume change frequently; alternate high intensity (heavy loads or explosive sprinting) with an appropriate level of volume (repetitions and sets) to allow for optimal recovery and adaptation.

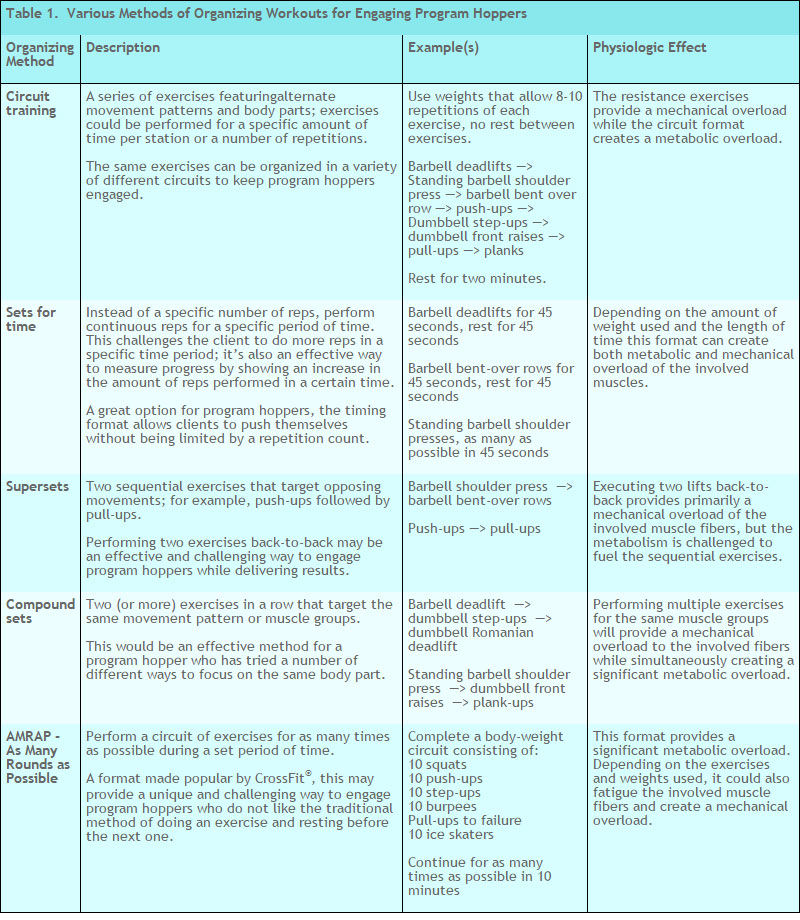

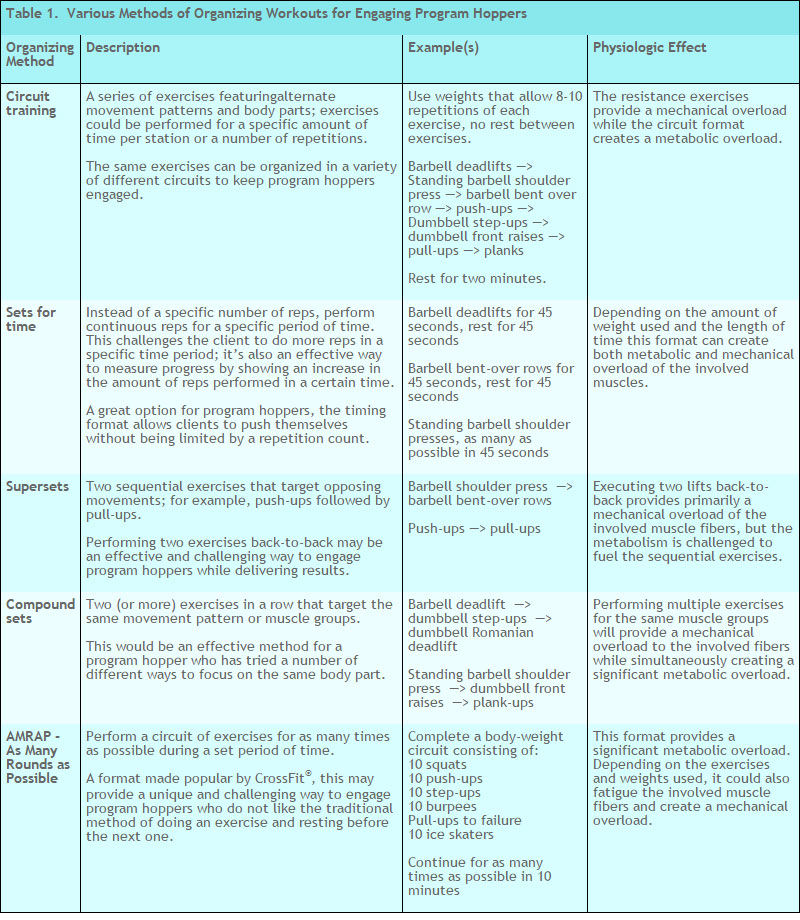

If you work with program hoppers or clients who are always interested in doing something different, using undulating periodization as a way to constantly change the structure of the program could be an effective strategy. This approach will allow you to stay consistent with exercise selection to facilitate optimal motor learning, while providing a way to change the other variables of an exercise program (intensity, repetitions, sets and rest interval) to create a different workout experience for each training session. Table 1 identifies a variety of different methods for creatively organizing the variables of program design to keep workouts interesting for program hoppers.

The examples of program design provided in Table 1 make it relatively easy to structure a constantly changing program for a client. For example, the focus could be on circuit training for one workout, the next on a combination of supersets with drop sets, and the following workout could be a form of AMRAP. Each workout could use the same basic exercises to allow the client to continually improve movement skill, but apply a different amount of training intensity and volume to keep the program-hopping client constantly challenged.

Turn Exercise into a Game

Another reason why a client might be a program hopper is that he or she may be extremely competitive, with a history of either playing team sports or training for individual competitions. Athletes might spend hours on the court or field practicing, but dread being in the weight room because of the limited amount of stimulation or competition. These clients may not be interested in traditional methods of doing a bench press for the sake of doing a bench press, but may be properly stimulated by making the exercise a competitive game. Using the bench press as an example, you can use the same weight for three different types of bench press—barbell, dumbbell or plate-loaded machine—and challenge the client to see the highest number of repetitions he or she can perform while on each piece of equipment.

Because they require focus and provide a sense of challenge, games are also an effective option for program hoppers who become easily distracted while exercising. Using games shifts the focus of a training session from exercise to play, which may be a key strategy for helping a program-hopping client learn how to find an activity that he or she enjoys. Jonathan Ross has been successfully using games for years as a way to make exercise fun, more engaging and reduce the perception of physical activity as “work.”

Using undulating periodization with all of the options for organizing sets or playing exercise-based games are just two examples of how to create workouts to engage clients who are easily distracted and always looking for the next exercise trend. Helping clients identify specific goals, combined with understanding how to use the science of exercise to make working out fun and engaging, can be an effective way to help clients achieve lasting results. If your clients see results, they will be more likely to not only continue on as clients, but to refer you to their friends who are seeking the same results for themselves.

References

Baechle, T. and Earle, R. (2008). Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning, 3rd

edition. Champaign, Ill.: Human Kinetics.

Bompa, T. (1999). Periodization: Theory and Methodlogy of Training, 4th edition.

Champaign, Ill.: Human Kinetics.

Schmidt, R. and Wrisberg, C. (2004). Motor Learning and Performance, 3rd edition.

Champaign, Ill.: Human Kinetics.

Siff, M. and Verkoshansky, Y. (2009). Supertraining, 6th edition. Denver, Colo.: Supertraining Institute.

Wilson, J. et al. (2012). Concurrent training: A meta-analysis examining interference of aerobic and resistance exercises. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26, 8, 22932307.

by

by

Just like learning a language requires knowing the fundamentals before becoming fluent, maintaining consistency of exercise selection can help clients experience continuous improvement. This, in turn, helps them develop greater levels of self-efficacy, which can lead to better long-term results. In addition, mastering the foundational movement skills involved is essential before increasing the intensity or challenge of an exercise. Changing exercise programs frequently before an individual has a chance to automate the involved movements means the client won’t be able to progress the intensity to the highest level he or she might be capable of achieving. “When jumping around, you are not necessarily allowing yourself to fully adapt to any one modality,” ACE Senior Consultant and owner of Movement First in New York City Chris McGrath tells his clients. “This makes ‘mastering’ a single modality unlikely, which ultimately interferes with maximizing results.”

Just like learning a language requires knowing the fundamentals before becoming fluent, maintaining consistency of exercise selection can help clients experience continuous improvement. This, in turn, helps them develop greater levels of self-efficacy, which can lead to better long-term results. In addition, mastering the foundational movement skills involved is essential before increasing the intensity or challenge of an exercise. Changing exercise programs frequently before an individual has a chance to automate the involved movements means the client won’t be able to progress the intensity to the highest level he or she might be capable of achieving. “When jumping around, you are not necessarily allowing yourself to fully adapt to any one modality,” ACE Senior Consultant and owner of Movement First in New York City Chris McGrath tells his clients. “This makes ‘mastering’ a single modality unlikely, which ultimately interferes with maximizing results.”