Faster Steps, Greater Impact: How Walking Pace Enhances Longevity and Functional Fitness

Walking is often the unsung hero of physical activity. It’s accessible, low-impact and appropriate for nearly every population. But new research suggests that how fast someone walks—not just how often—might be a critical determinant of long-term health, functional fitness and even mortality risk.

Taken together, two recent studies, one from the American Journal of Preventive Medicine and another from PLOS ONE, present a powerful message: Walking at a faster pace can lead to significant improvements in longevity and physical function, particularly among older adults and those at greater risk of chronic conditions.

This article breaks down the science behind these findings and explores how you can use them to better educate and guide your clients—especially those with frailty, older adults or those navigating health disparities.

Study 1: Fast Walking Reduces Mortality, Even in Vulnerable Populations

The American Journal of Preventive Medicine published a major population study analyzing data from nearly 80,000 participants in the Southern Community Cohort Study (SCCS). This group, consisting largely of low-income and Black Americans, was followed for more than 16 years.

The key finding, according to lead investigator Dr. Wei Zheng of Vanderbilt University Medical Center, is that fast walking—even as little as 15 minutes per day—was associated with a 20% reduction in total mortality. “This benefit remained strong even after accounting for other lifestyle factors,” explains Dr. Zheng. By contrast, more than three hours of slow daily walking yielded only a 4% reduction.

This is critical for health and exercise professionals working in communities that experience higher rates of chronic disease and premature death. Not only is walking a feasible activity in resource-limited settings, but the benefits of increasing walking intensity, not just duration, may offer a strategic intervention to address health disparities.

Even more encouraging is the finding that the positive effects of brisk walking were independent of other physical-activity behaviors, such as gym workouts or recreational sports. In other words, walking fast was beneficial even for people who weren’t otherwise very active.

The mortality risk reduction was especially strong for cardiovascular disease, aligning with known benefits of aerobic exercise, including improved cardiac output, enhanced vascular function and better blood pressure control. And while faster walking helps everyone, those with comorbidities saw even greater improvements, which highlights its relevance for individuals who are managing conditions like hypertension, diabetes or obesity.

Study 2: Walking Cadence Improves Functional Capacity in Older Adults

While study 1 focused on longevity, the second study looked at the impact of walking on functional fitness. Specifically, researchers at the University of Chicago and partnering institutions explored how changes in walking cadence (steps per minute) impact physical performance in frail and prefrail older adults. Their study, published in PLOS ONE, focused on residents of retirement communities who participated in a four-month structured walking program.

Participants were divided into two groups:

- Casual Speed Walking (CSW): Walked at a comfortable, self-selected pace

- High-intensity Walking (HIW): Encouraged to walk “as fast as safely possible,” targeting 70% of their estimated heart rate max

Using accelerometers to measure cadence, researchers found that those in the high-intensity group averaged 100 steps per minute, compared to 77 steps per minute in the casual group. This increase in cadence was directly linked to meaningful improvements in the 6-minute walk test, which is a standard measure of functional capacity.

“People who haven’t experienced frailty can’t imagine how big a difference it makes to be able to not get tired going to the grocery store or not need to sit down while they're out,” said study lead Dr. Daniel Rubin.

The findings offer a clear takeaway: Increasing walking cadence by just 14 steps per minute above an individual’s baseline can lead to significant improvements in walking endurance and independence.

Why is this so important? Functional decline is a hallmark of frailty and a predictor of loss of independence. Simple interventions like cadence-guided walking can delay or reverse this trend—and may offer an alternative to more complex exercise programs that some older adults might find intimidating.

Why Cadence Matters More Than You Think

The concept of walking “intensity” can be hard to quantify, especially in older populations where tools like heart-rate monitors may be less reliable for those who take medications such as beta blockers that can lower heart rate. Ratings of perceived exertion and the talk test are helpful but subjective.

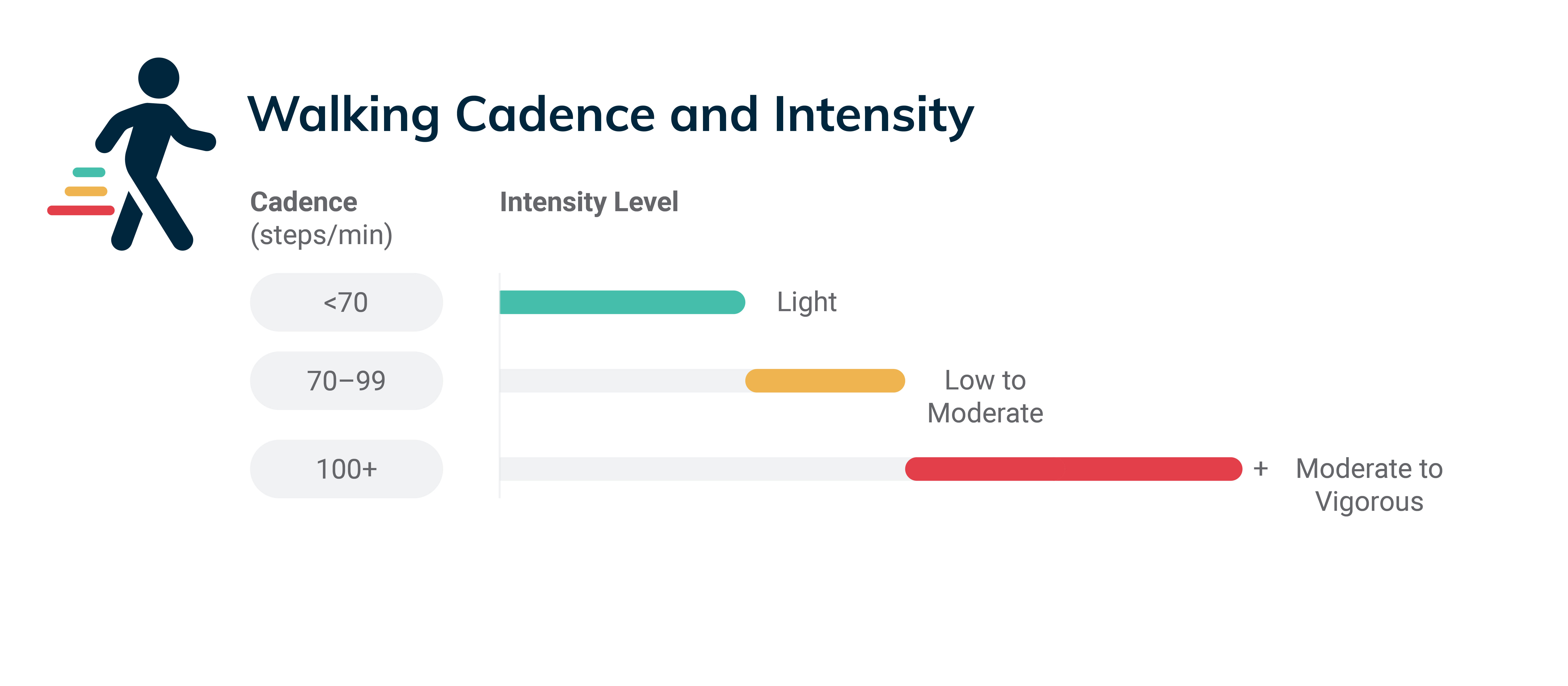

For these reasons, cadence is gaining traction as an objective, intuitive and measurable indicator of walking intensity. Research has shown that:

- Cadence correlates strongly with moderate-intensity activity levels.

- One hundred steps per minute is widely accepted as the threshold for moderate intensity.

- Cadence can be accurately measured with simple tools, such as smartphone apps and smartwatches.

The cadence approach is especially valuable for health and exercise professionals working with frail or older adults, where the risk of overexertion must be balanced against the need to challenge the cardiorespiratory system. See Figure 1 below for a visual summary of cadence and its corresponding intensity levels.

Figure 1. Walking Cadence and Intensity

How to Help Your Clients Measure Cadence

1) Manual count. During a walk test, start a 30-second timer and have the client count every step. Multiply by 2 to get steps per minute. To simplify counting, they can track only right-foot strikes—count for 60 seconds and multiply by 2, or count for 30 seconds and multiply by 4. Repeat at least twice and average the results for accuracy.

2) Wearable or app method. Show clients how to use a pedometer, smartwatch or phone app to log total steps during a set interval (for example, a 10-minute walk). Divide total steps by the number of minutes to find steps per minute. Example: 700 steps in 10 minutes equals 70 steps per minute. Encourage consistent device placement and basic setup (time, stride length) so readings are comparable over time.

Coaching tip. Set specific cadence goals—such as increasing by 5 steps per minute over two to three weeks—rather than focusing only on distance or duration. Have clients record cadence alongside perceived exertion and comfort to ensure that form and intensity stay appropriate.

Putting the Research Into Practice as a Health and Exercise Professional

The findings from both studies carry meaningful implications for health and exercise professionals, particularly if you are working with older adults or populations facing health disparities. As with any exercise program design, the challenge lies not only in understanding the research but in translating it into behavior change that resonates with each individual client. And when it comes to walking, the shift from simply doing it to doing it with greater intention and intensity can make all the difference.

A good starting point is to get a sense of a client’s current walking habits. While total time spent walking is certainly relevant, cadence—the number of steps taken per minute—offers a practical window into exercise intensity. By observing a client’s comfortable walking pace, either in a session or by using an app or wearable device, you can begin to identify opportunities for gradual progression. Most clients don’t need to be told to hit a specific number; rather, they need to be guided toward walking “a little faster than usual,” a phrase that’s both intuitive and accessible.

As clients begin to increase their cadence, even by just 10 to 15 steps per minute, they may notice improvements in their stamina, confidence and overall energy levels. Framing this as a process of reclaiming or maintaining independence can be particularly motivating for older adults, especially those navigating frailty or functional decline. Highlighting how walking at a brisker pace can translate into easier grocery trips, less fatigue while doing errands or greater ease keeping up with grandchildren makes the intervention feel relevant and achievable.

For those who already walk regularly but don’t feel they’re getting results, the idea that walking faster, even for short periods of time, can unlock new benefits is often an empowering revelation. Encourage clients to treat brisk walking like an interval. For example, urge them to walk at a faster pace for one or two blocks, then recover at a more comfortable speed. These short bouts can be gradually extended, providing a clear sense of progress without feeling overwhelming.

If you work with underserved communities, keep in mind the unique barriers these clients may face. Walking remains one of the most accessible forms of physical activity, but safe walking environments are not always guaranteed. In these cases, indoor walking—whether at a mall, a local community center, or a long hallway in a church or apartment building—can be a valuable alternative. Group walking programs, where available, may also provide social reinforcement and added safety.

Finally, don’t underestimate the value of explaining the “why” behind the shift in pace. Clients may associate exercise intensity with risk or discomfort, particularly those managing chronic conditions or new to physical activity. Reassure them that walking a little faster is not about exhaustion or high performance, but about stimulating the heart, lungs and muscles enough to improve function and reduce disease risk. When clients understand the specific health benefits, like improved cardiovascular efficiency, better blood pressure control or increased endurance for daily activities, they’re more likely to commit to the effort.

Walking may be simple, but its impact is profound. And as the research now confirms, increasing the pace of that walk can make it even more powerful. As a health and exercise professional, your role is to help clients see this path clearly and walk it, step by purposeful step, toward better health and longevity.

Final Thoughts

Walking has long been a cornerstone of movement-based health promotion. But now, we know it’s not just about how much your clients walk—how fast they walk may matter even more.

The studies covered here provide compelling, evidence-based guidance for health and exercise professionals working across the lifespan, and particularly for those who work with aging or underserved populations. As you design programs and coach behavior change, consider cadence as a critical component of walking programming. Small increases in pace can lead to big leaps in quality of life and even add years to it.

More Articles

- Certified™: October 2025

14-Minute Interval Workouts: VO2 Pyramids, Hills and Sprint Circuits

Health and Fitness Expert

- Certified™: October 2025

Fit Together: Coaching Strategies for Couples, Friends and Siblings

Contributor

- Certified™: October 2025

Unpacking the Ultra-processed Food Problem: What Health and Exercise Professionals Need to Know

Contributor

- Certified™: October 2025

A Pro’s Guide to Muscle Mechanics: The Lower Leg and Foot

Health and Fitness Expert

by

by