Exclusive ACE study exposes critical gaps in qualifications for those who coach youth sports.

Whether it’s soccer, basketball, football, lacrosse, gymnastics, swimming, baseball or one of many other popular sports here in the United States, there are more than 40 million youth now playing organized sports. Over the past 20 years, that number has grown steadily and, in turn, the demand for youth coaches has quadrupled. These days, according to the National Council of Youth Sports, there are more than two million adults serving as youth coaches.

While the nation’s youth coaches, the majority of whom are volunteers, are indeed a dedicated crew, just how prepared and qualified are they to coach your children? Certainly, they can teach kids how to pass a soccer ball, catch a pop fly or swim the breaststroke, but there is more to being a coach. Whether advising kids on how to stay hydrated during games, at what age to begin strength training, or what to do following a concussion, coaches must be relied upon to help guide and protect young athletes.

In an effort to gauge just how prepared and qualified our nation’s youth coaches are, the American Council on Exercise (ACE), America’s Workout Watchdog, enlisted the help of the exercise scientists at the Clinical Exercise Physiology program at the University of Wisconsin, LaCrosse.

THE STUDY

Led by John Pocari, Ph.D., and Courtney Carlson. M.S., researchers collaborated with ACE to develop a 40-question survey covering seven important topics related to exercise physiology, practice design, hydration, nutrition, basic first aid and acute injury management, concussion care and strength-training knowledge. The test also surveyed the demographic details of each respondent including:

- Age

- Education level

- Major field of study

- Age level coached

- Whether the coach was paid or not

- Highest level of sports participation by the coach

The research team and officials from ACE reached out to anyone who had coached youth sports, from children to 18-year-old athletes, to take the test. In all, 70 youth coaches completed the survey.

THE RESULTS

Immediately following the completion of the surveys, researchers crunched the data. On average, the score for all respondents was 28.7 correct out of 40 questions, which works out to about a 72 percent score on the questionnaire; respondents answered approximately 11 questions incorrectly. “That would be a C,” notes Porcari. “They’d flunk out of our graduate program with grades like that.”

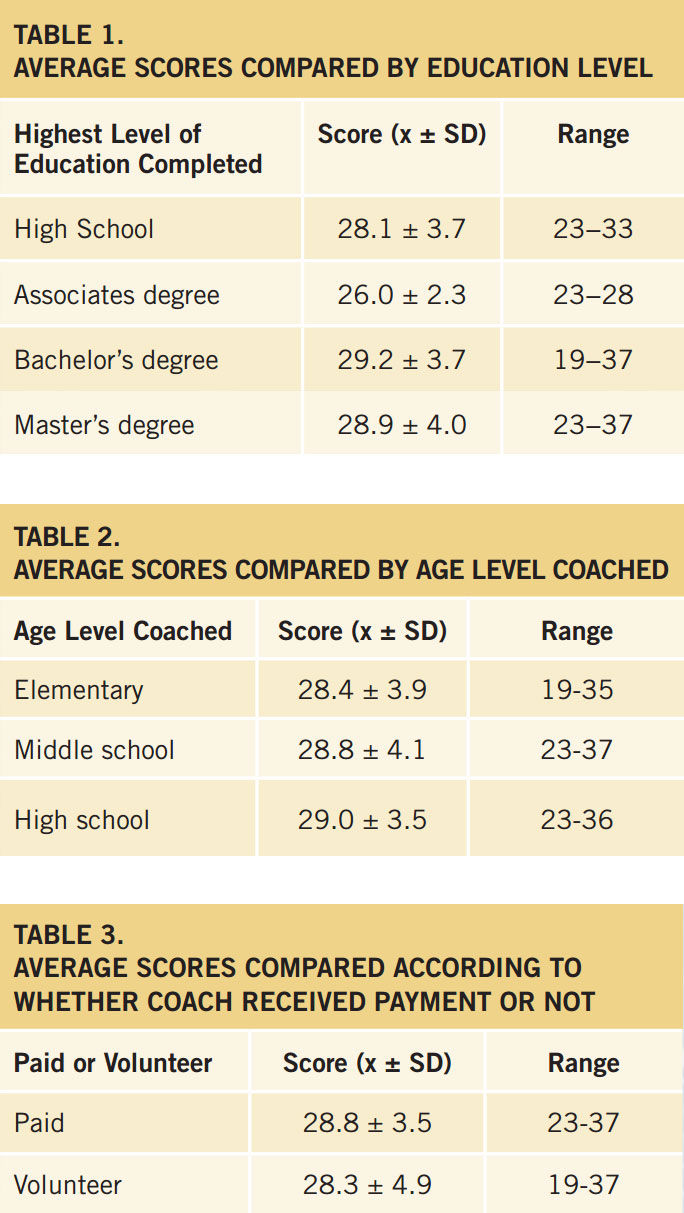

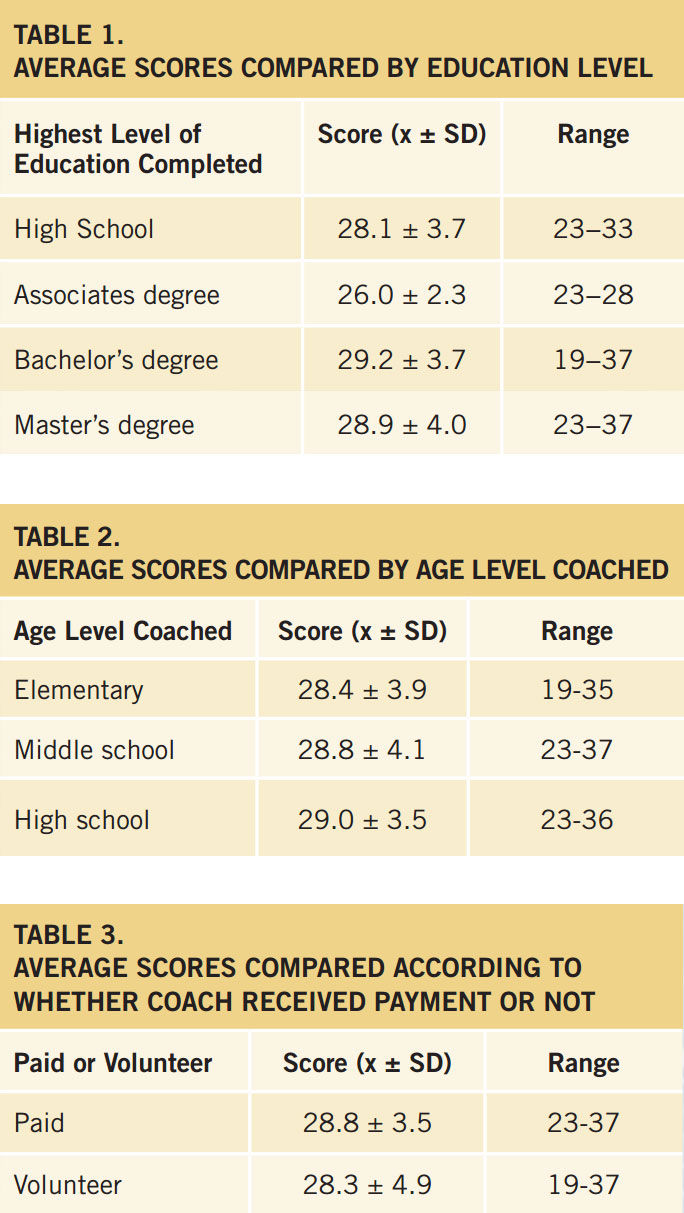

“What we found is that there’s an overall lack of knowledge in each of the categories. And there really wasn’t much difference between demographic data,” says lead researcher Carlson. “It didn’t matter if they were male or female, their education level, different degrees or what level they coached, or if they were paid or not, we didn’t find any difference in their total score” (see Tables 1-3).

The only significant difference was that health science majors did markedly better than any other college major for the respondents who had completed college as their highest level of education, notes Carlson.

In all, nine questions stood out as the most often missed, with (in all but one instance) 50 percent or more of respondents answering those questions incorrectly (see sidebar). Four of those questions related to hydration, while the others touched on strength training, nutrition and concussions. Besides major problems with the hydration questions, Porcari notes that half of respondents were unfamiliar with Second Impact Syndrome, a dangerous and often fatal concussion-related complication.

The 9 Questions Most People Got Wrong…

Researchers found nine questions that a majority (approximately 50% or greater) of the respondents answered incorrectly (correct answer is shown in bold-face text).

Question 5: Fluid intake should be dictated by taste preference, since volume of intake, rather than fluid content is the most critical issue in child athletes.

A. True: 15.7%

B. False: 84.3%

Question 8: Rapid swelling of the brain following a second head injury that occurs before the symptoms of a previous head injury have resolved is referred to as _________.

A. Second Cerebral Injury: 17.1%

B. Second Impact Syndrome: 52.9%

C. Second Relative Abrasion: 0%

D. Post Concussive Syndrome: 30%

Question 10: If children are ready to participate in organized sports, they are also ready for some type of strength training.

A. True: 28.6%

B. False: 71.4%

Question 11: Which two micronutrients are MOST likely to be deficient in youth athletes?

A. Calcium and vitamin D: 31.4%

B. Iron and vitamin C: 18.6%

C. Vitamin D and vitamin C: 10%

D. Calcium and iron: 40%

Question 26: What is a good way to monitor an athlete’s hydration levels during exercise?

A. Asking the athlete how thirsty he or she is after practice: 5.7%

B. Observing the athlete’s rate of sweating: 45.7%

C. Weighing an athlete before and after practice: 32.9%

D. Monitoring reaction time and coordination: 15.7%

Question 27: During which of the following is it MOST appropriate to consume electrolyte-supplemented beverages such as sports drinks?

A. When activity lasts longer than 30 minutes: 47.1%

B. During high-intensity strength-training workouts: 15.7%

C. Whenever participants are visibly sweating: 15.7%

D. When the schedule calls for repeated same-day sessions: 21.4%

Question 36: The performance of strength training by children and adolescents should be ______________.

A. Discouraged due to the potential for damage to their growth plates: 32.9%

B. Avoided due to the increased risk of musculoskeletal injury: 11.4%

C. Allowed only if the youth are mature enough to exercise on their own: 21.4%

D. Encouraged to reduce the risk of sports-related injuries: 34.3%

Question 38: Nausea, initially pale and then flushed skin and light headedness are some acute signs and symptoms of what?

A. Heat cramps: 2.9%

B. Dehydration: 47.1%

C. Hypothermia: 0%

D. Heat stroke: 50%

Question 39: What percentage of a child’s caloric intake should be carbohydrates?

A. 55-70%: 48.6%

B. 25-35%: 44.3%

C. 12-15%: 4.3%

D. 70-85%: 2.9%

That said, Porcari also says it’s important to note that these youth coaches appeared prepared in other areas, with 74 percent (52 out of 70) of coaches reporting being first-aid certified, while 73 percent (51 out of 70) of coaches were also CPR certified. Similarly, 54 percent (38 out of 70) had AED training.

THE BOTTOM LINE

“I think this study really pointed out areas of weakness where education could really be helpful for youth coaches,” says Porcari.

While the majority of respondents missed several important questions, the most concerning mistakes were those that related to potentially dangerous conditions such as overheating and lack of proper hydration, and Second Impact Syndrome, where nearly half of the respondents answered the question incorrectly. “That’s pretty scary,” he says. “That’s one area where making people aware of the potential consequences of sending players back into the game too soon after a concussion could be crucial to saving a kid’s life. Most coaches know that concussions are bad, but they don’t know the consequences, that if you send a kid back in too soon and he gets hurt, it could turn his brain to mush.”

Researchers note that semantics and the wording of the questions could possibly have affected the number of mistakes made by youth coaches, but experts at ACE maintain that the results cannot be overlooked. Whether it’s failing to properly hydrate youth athletes resulting in dangerous heatstroke, or missing key warning signs of Second Impact Syndrome, without proper education, many coaches are putting youth athletes in undue danger.

ACE Chief Science Officer Cedric X. Bryant, Ph.D., acknowledges that, "while volunteer coaches form the backbone of non-school-organized youth sports and are very well intentioned and dedicated, the results of this study suggest that many would benefit from receiving educational information and training on safety and injury prevention as it pertains to young athletes." That said, getting these volunteers to coach can be a daunting task on its own, not to mention how challenging it may be to require or strongly encourage those volunteers to also take supplemental education to better prepare themselves for coaching safely and effectively.

Porcari recommends that steps be taken by youth-sports organizations to create educational programs to better prepare these coaches. “It doesn’t need to be voluminous, like some 40-page chapter. The info can just be short and sweet and tailored to each sport,” he says. “If they can make it bite-sized and palatable enough where people are going to want to do it, youth coaches will become more knowledgeable, able to understand the basic topics of exercise physiology, and better able to create a safer and more enjoyable environment for young athletes.”

This study was funded solely by the American Council on Exercise.