Much like indoor cycling and boxing workouts, which have enjoyed a resurgence in popularity in recent years, functional training is a once-popular fitness trend that is on the verge of making a comeback. An extremely popular term, almost to the point of overuse, that emerged in the late 1990s, functional training was used to describe workouts that focused on improving the skills of balance and coordination over the development of muscular strength. The theory behind functional training was that exercises performed on an unstable surface could enhance proprioception, the component of the central nervous system that receives sensory information from both the external environment and internal sensory nerve endings, to increase muscle activation. Like many trends, what began with good intent—helping clients improve coordination to gain better control of their bodies—ended up becoming completely overused. The result was that many fitness programs focused more on complexity as opposed to intensity, with clients doing exercises better suited for a circus than for increasing muscle hypertrophy.

Here’s how the Oxford English Dictionary defines functional: “Of having a special activity, purpose or task. Relating to the way in which something works or operates. Designed to be practical and useful, rather than attractive.” The first iteration of functional training took this definition literally, with workouts that emphasized proprioception over force production. The goal of many “functional” workouts was to help clients have better coordination, not necessarily improve muscle definition or increase overall strength. In an effort to outdo one another with creative or overly complex exercises on balance implements, many exercise professionals overlooked the fact that it is the intensity of exercise—specifically, the actual amount of resistance used—that actually improves muscle definition and strength, not the ability to balance or control one’s body on an unstable surface.

By the mid-2000s, functional-training techniques featuring body-weight movements or low-intensity loads became were eclipsed by high-intensity interval training (HIIT) programs featuring body-weight exercises borrowed from gymnastics, as as exercises using barbells, kettlebells and oversized medicine balls, to develop maximal strength and power. Fitness consumers quickly realized that high-intensity workouts that involved lifting heavy weights and doing explosive exercises burned more calories, increased lean muscle mass and improved definition much more effectively than standing on an unstable piece of balance equipment. As high-intensity workout programs became more popular, exercise selection evolved from using resistance tubing, medicine balls and balance platforms to incorporating Olympic platforms for barbell lifts such as the snatch and clean-and-jerk, kettlebell swings, and heavy medicine ball throws to apply the necessary overload to impose muscle growth.

All Good Things Eventually End

By the early 2010s, the popularity of high-intensity training grew exponentially because it delivers what fitness consumers want: RESULTS. However, all good things must come to an end. From aerial yoga workouts to Zumba classes, the problem with any fitness technique or modality that becomes a popular trend is that too much of any single type of exercise leads to unbalanced training. This is a common reason for getting stuck on plateaus, where the body is no longer making adaptations to the imposed stimulus, or overuse injuries caused by overstressing the involved tissues. For this reason, high-intensity training works best when used in moderation in combination with other types of less-stressful exercise to allow the body to fully recover and adapt to the exercises performed in the workouts.

As the third decade of the 21st century rapidly approaches, it appears that the concept of functional training featuring low-intensity movement training is beginning to reemerge as a beneficial exercise technique. This time around, however, many health and exercise professionals are using low-intensity exercise to improve movement skill and combining it with high-intensity training techniques to increase energy expenditure and promote muscle growth, resulting in what many seasoned veterans are referring to as Functional Training 2.0.

Truly Functional Training

In some respects, functional training never truly went away. Quality health and exercise professionals have always designed programs that featured high-intensity exercises, but were also based on a strong foundation of functional movement. Mike Boyle, the author of New Functional Training for Sports and the owner of Mike Boyle Strength and Conditioning located outside of Boston, Mass., never veered too far away from a functional approach to exercise.

“Functional training is best characterized by exercises done with the feet in contact with the ground and, with few exceptions, without the aid of machines,” writes Boyle. Using this definition, many of the high-intensity barbell, kettlebell and medicine ball exercises are functional in that they require individuals to execute the lifts from a standing position.

A critical mistake of the initial approach to functional training was to forgo the use of heavy weights or explosive movements, which are necessary for muscle growth. As functional training is making its way back into the fitness lexicon, it appears as if it is with a solid understanding that exercise intensity is an essential aspect of programming, because high-intensity training is the most effective means of providing the metabolic and mechanical overloads responsible for muscular development. Conversations with health and exercise professionals offer different insights into why functional training is staging a comeback, and how the concept has evolved during the years it has been relegated to the back corners of a exercise professional’s toolbox.

One significant factor promoting a return to functional training techniques is an aging population that understands that enhancing mobility can have a greater impact on pain-free movement than simply lifting heavy weights.

“It’s apparent that the aging process does not stop for anyone,” observes David Harris, vice president for Health and Human Performance at Equinox Health Clubs. “At Equinox, we have seen that even as our members age, they still pursue their favorite physical activities like running marathons, training for triathlons or maintaining the musculature of a bodybuilder. Our goal is to help our members...feel as if they have no limitations, [and] our team will do anything to help our members maintain or improve their functional capacity.”

A new and novel trend that is encouraging the use of functional training techniques is a greater emphasis on recovery—specifically, how the body recovers from, and adapts to, the stresses imposed by an exercise program. An important recovery strategy is to perform low-intensity exercise the day after an extremely challenging high-intensity workout, and multiplanar movements combined with light weights are an effective solution.

“I believe that the fitness industry is coming full circle and returning to a place of functional training due to the amounts of stress that HIIT and explosive weight training have been putting on people’s bodies,” asserts Christy Giroux, a personal trainer for more than 20 years and co-owner of Prime Fitness (with her husband Eric) in Gaithersburg, Md. “A number of injuries like tendinitis or impingement can be related to overuse without adequate rest. Truly functional training addresses not only the exercises performed in the workout, but also the post-exercise recovery strategies that are important for remaining injury-free.”

Rafal Tokicz, an Advantage Trainer at the Equinox Sports Club in Washington, D.C., with almost 15 years of industry experience, agrees. “The recovery process—actually allowing the body to adapt to the stresses of exercise—is often overlooked,” says Tokicz, “yet it is very important to help clients experience the adaptations necessary to improve their overall health and functional strength.”

As those who entered the industry during the high-intensity era gain more experience and knowledge, they are developing a better understanding of that the fact that moving better is a necessary prerequisite for being able to achieve optimal levels of strength and power. As a result, the programs they design and coach are featuring more functional movements along with traditional high-intensity exercises.

“Many trainers are realizing that running their clientele into ‘brick walls’ of training intensity is leading to injuries and clients becoming discouraged at their attempt to become fit,” explains Kevin Mullins, a Tier 3+ personal trainer at the Equinox Sports Club in Washington, D.C., who started his fitness career in 2010 during the high-intensity period. “Elite coaches know how to combine the practices of functional movement and strength training to develop programs that are changing bodies and lives simultaneously.”

Metabolic Conditioning Is Still a Thing

In the early 2000s, functional training was often used for the cardiorespiratory component of exercise as well as the strength component, with many health and exercise professionals using exercise circuits to elevate the heart rate. This approach could indeed help improve general fitness, but does not provide sufficient overload to induce an anabolic response from the endocrine system. HIIT workouts that elevate blood lactate also increase the production of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factors, two hormones essential for muscle growth (Rahimi et al., 2010). This new era of functional training brings with it a better understanding of the role that metabolic conditioning plays in exercise programs for the general public and continues to utilize HIIT in addition to other forms of metabolic conditioning.

“When it comes to overall functional capacity, the cardiorespiratory system is extremely important because it can help keep blood pressure stable while reducing the risk of the onset of diabetes,” explains Harris. “At Equinox, we want our personal trainers and coaches to know how to design exercise programs that access the various energy substrates because that is a necessary component of helping clients achieve and maintain the lean muscle mass they want.”

While HIIT can be effective, too much of it could lead to overtraining. For this reason, it is important to include other types of metabolic conditioning such as steady-state training (SST), which features a high volume of work to enhance aerobic capacity. Low-intensity interval training (LIIT) uses lower-to-moderate intensity intervals combined with periods of active rest to improve the efficiency of the cardiorespiratory system to deliver oxygen to working muscles. Variable (duration) interval training (VIT) alternates between short, intermediate and long periods of work to challenge the body to be able to work efficiently for different lengths of time. In addition, variable intensity interval training (VIIT) alternates between periods of low-, moderate- and high-intensity exercise to provide an overload.

The true challenge is that there is no, single “best” way to design a program, so each individual client will have his or her own particular needs that will dictate the intensity and duration of the workouts.

“Not all interval training has to be high intensity,” urges Irene Lewis-McCormick, an ACE Certified Personal Trainer and Health Coach who coaches for OrangeTheory Fitness in Akeny, Iowa. “Using SST, VIIT, VIT, LIIT and HIIT to alternate work intervals between different levels of intensity and durations of time can help ensure that clients don’t adapt to using any one energy system over another.”

Redefining Functional Training

Your clients hire you because they are interested in one thing: results. While there are general categories of exercise outcomes, such as weight loss, muscular development, making the transition back from physical therapy to full activity, performance enhancement for a particular sport or simply improving health, every client should first take the time to identify some specific expectations for what he or she wants to achieve with an exercise program. Whether you’re just starting your career or you’ve been working in the fitness industry for years, it’s important to acknowledge that any exercise can be functional, as long as it relates to a client’s stated goals, existing level of fitness and overall movement skill.

“Function is specific to each individual’s goals, needs and current condition,” explains ACE Certified Personal Trainer and Master Trainer Keli Roberts. “A single-joint exercise could be functional if used the right way for the needs of the client.” Tokicz echoes Roberts’ approach: “To me, functional means anything that helps a client get to his or her fitness or wellness goal. The specific exercise process and the subsequent adaptations should vary according to the benefits a particular client wants out of his or her program,” Tokicz says.

Sonja Friend-Uhl, a Boca Raton, Fla.-based ACE Certified Personal Trainer and world record holder for the Master’s Women Indoor Mile, has been working in fitness for more than two decades and uses a variety of different methods of program design for her clients. She describes the benefits of functional training as “improved mobility, stability, balance and flexibility, which leads to greater levels of overall strength and the ability to successfully perform all of the basic movement patterns, which is relevant to many activities of daily living.”

As the fitness industry transitions back into a phase where functional training becomes the foundation for many programs, be careful that you don’t go overboard with only one particular mode of exercise. A well-rounded program should include high-, moderate- and low-intensity exercises so a client’s body never adapts to any one specific level of difficulty.

“When it comes to designing any exercise program for a client, my primary consideration is that it is sustainable over a long period of time,” said Josh Meltzer, fitness manager and a Tier 3+ personal trainer at Equinox in Carlsbad, Calif. “Longevity is the name of the game. When repeating the same sort of program day after day, year after year, it’s inevitable that an important component like mobility or recovery could be overlooked, which could mean not reaching full potential or becoming injured,” adds Meltzer.

Helping Clients Get Results

The Functional Movement and Resistance Training component of the ACE Integrated Fitness Training® (ACE IFT®) Model of exercise program design organizes exercises according to the amount of stress applied to the physiological systems of the human body. Stability and mobility training, the initial phase of the ACE IFT Model, focuses on low-intensity bodyweight movements to help improve joint function and develop the muscular endurance necessary to maintain good posture. Movement training, the second phase of the ACE IFT Model, is the progression to exercises that integrate stability and mobility in an effort to improve overall movement efficiency. Intensity in this phase can either feature body weight or tools such as tubing or cable machines, medicine balls, sandbags and dumbbells. The load training phase relies upon either external resistance or body-weight movements performed to a point of momentary fatigue to create the mechanical or metabolic overload necessary to activate the type II muscle fibers responsible for improving muscle force output. Finally, the performance training phase of training adds a velocity component with exercises that require muscles to either generate force at maximal velocity to enhance power or to sustain a force over an extended period of time to improve endurance. In short, the ACE IFT Model provides a useful guide for how and when to apply appropriate levels of intensity, allowing you to create functional workout programs that deliver the results that clients want.

An exercise program does not need to be overly complicated, with different exercises for each body part, to produce results. It does, however, need to provide an adequate stimulus to initiate physiological changes in the body. Importantly, the ACE IFT Model addresses exercise as a function of movement. In the movement training phase, clients use low-intensity exercise to improve their efficiency in performing the patterns of the basic movements—hip-hinging, lunging, pushing, pulling and rotating—prior to working at the higher intensities required to make significant changes to the body. Similarly, the Load and Performance phases provide the structure for challenging workouts, based on intensity and speed of movement. When designing programs, the load and performance training phases can include exercises from the stability and mobility or movement training phases to alternate between periods of high and low intensity within the same workout or training cycle.

Friend-Uhl provides an excellent model of how to incorporate HIIT with functional training. “Functional movements are the heart of most of the programs I write for healthy adults. I often use them for active recovery during HIIT workouts,” she says.

Into Action

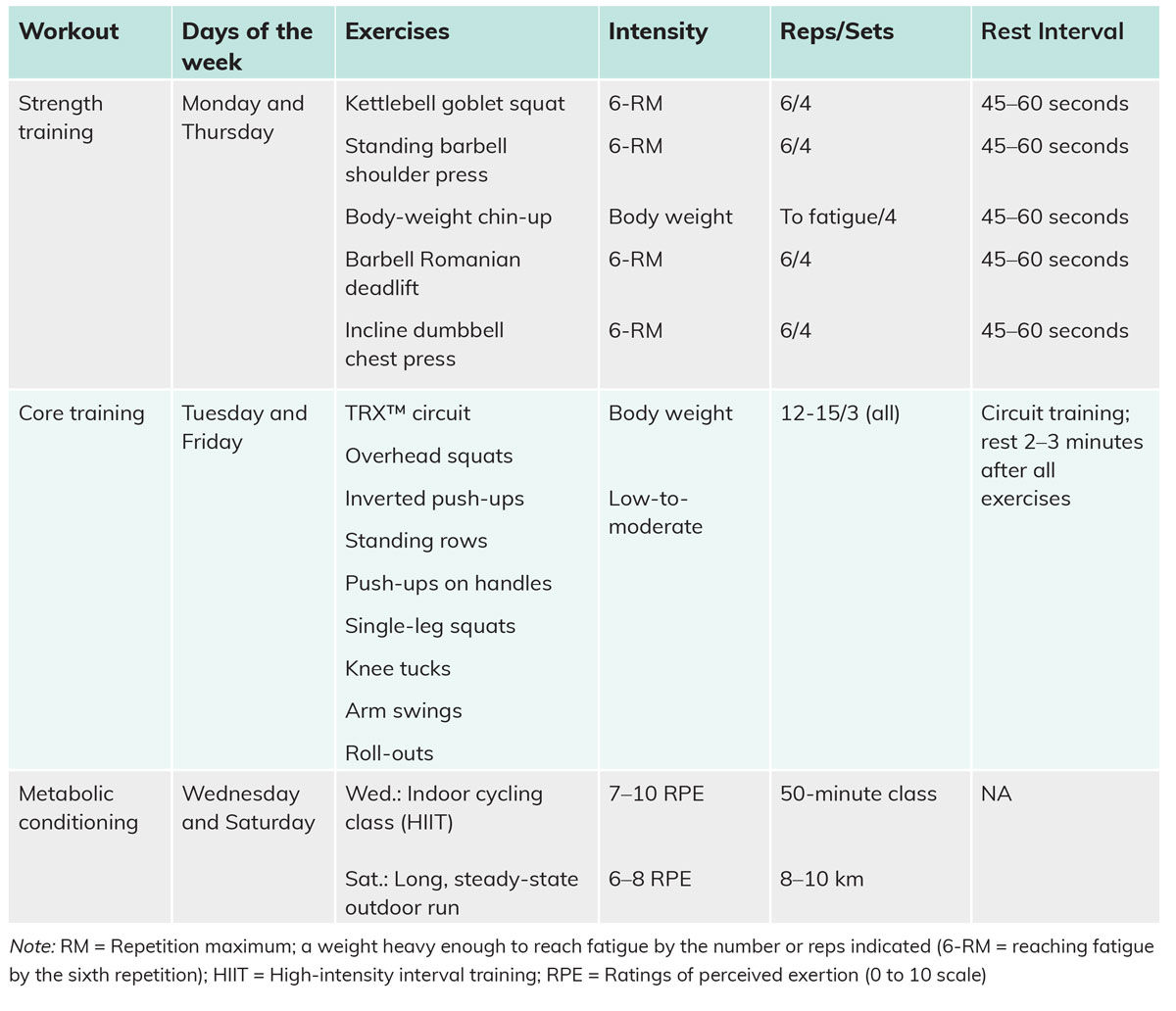

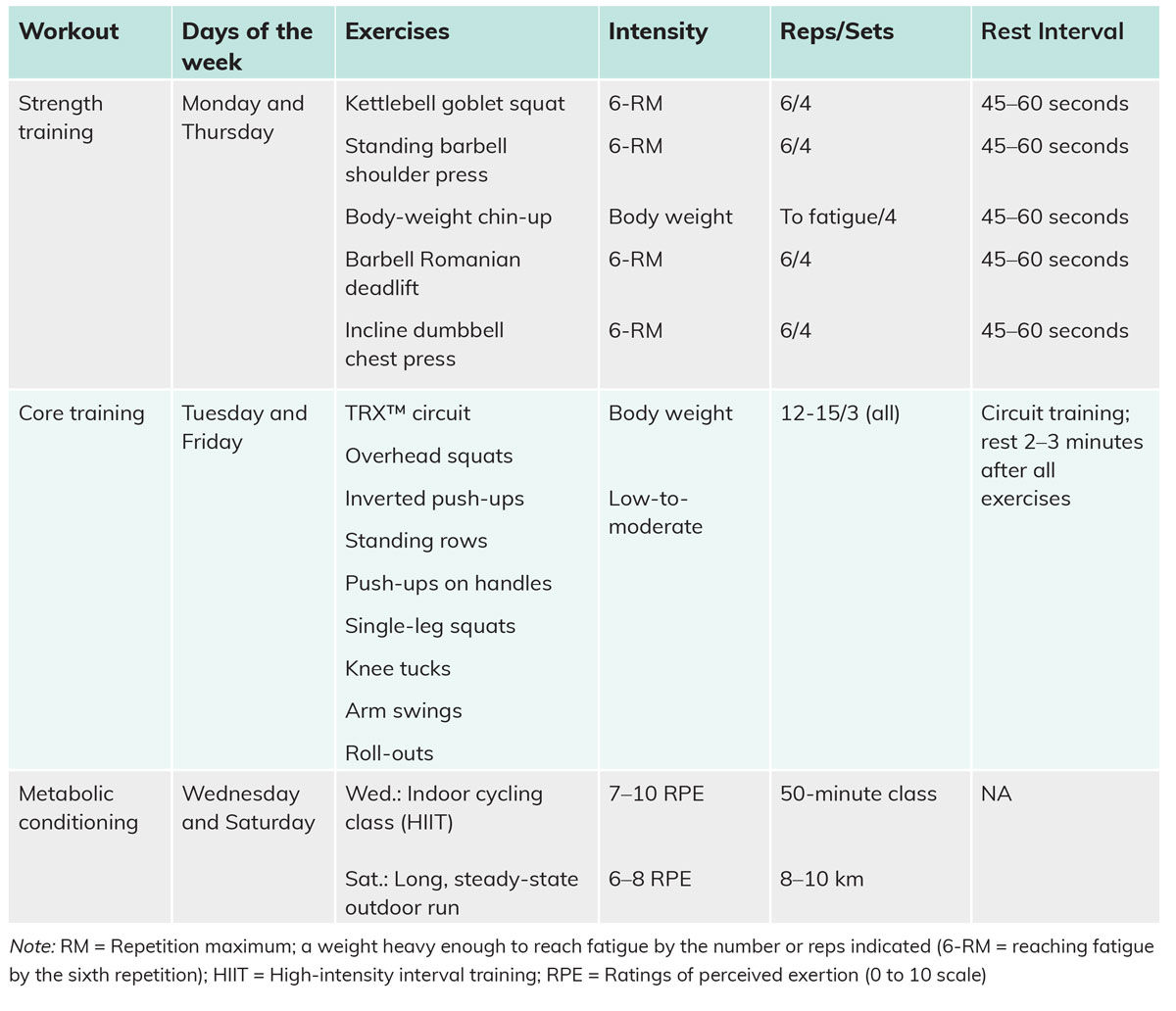

A modern adaptation of functional training should feature workouts that alternate between external loads for high-intensity strength training on one day, and low-intensity or body-weight exercises to promote motor learning and active recovery on the next day. This, in turn, should be followed by low-, moderate- or high-intensity metabolic conditioning on the third day. Of course, a client’s existing fitness level, goals and overall stress load will determine the exact structure of a program. In general, however, a perfect program would have two to three days a week of high-intensity exercise (either strength training or metabolic conditioning), two to three days of low- to moderate-intensity strength training using primarily body weight to promote recovery, and two to three days of metabolic conditioning. For example, a client with a goal related to cardiorespiratory training would spend more time working on metabolic conditioning at all levels of intensity, while a client interested in adding lean muscle would alternate between different levels of intensity for strength training.

The following workout provides an excellent example of how to combine varying levels of intensity into a single program. This program could be used for any apparently healthy adult without any existing injuries, who has had at least one full year of exercise experience and who has a goal of maintaining a healthy bodyweight while increasing overall levels of strength.

When it comes to designing workouts programs that work and facilitate long-term success, it is important to not follow any single mode of exercise, but instead to apply different methods to different clients based on their individual needs. And don’t follow the latest fad or waste money on gimmicky equipment. Rather, follow the advice offered by Juan Carlos Santana, the owner of the Institute of Human Performance in Boca Raton, Fla. and an international presenter: “Truly functional training is keeping clients happy by giving them a program to meet their particular needs.”

by

by