Study: High-intensity Interval Training May Be Fountain of Youth

There’s no question that exercise offers an extensive list of benefits, from boosting your immune system and helping you sleep better to reducing your risk of disease and extending your lifespan. In fact, researchers have long suspected that the benefits of exercise extend down to the cellular level, but know relatively little about which exercises help cells rebuild key organelles that deteriorate with aging. A new study published earlier this year in the journal Cell Metabolism may have uncovered the answer.

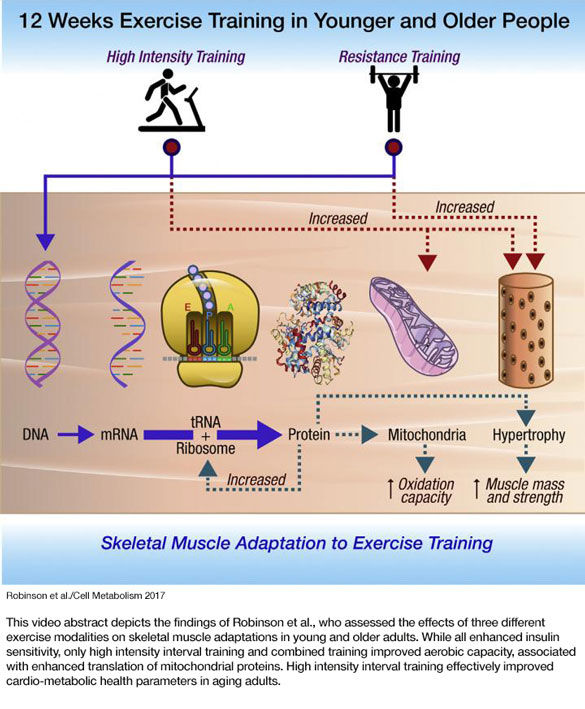

Specifically, researchers determined that exercise—and in particular high-intensity interval training in aerobic exercises such as biking and walking—causes cells to make more proteins for their energy-producing mitochondria and their protein-building ribosomes, effectively stopping aging at the cellular level.

“Based on everything we know, there’s no substitute for these exercise programs when it comes to delaying the aging process,” says study senior author K. Sreekumaran Nair, M.D., Ph.D., a physician and diabetes researcher at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. “These things we are seeing cannot be done by any medicine.”

The Study

The study enrolled 36 men and 36 women from two age groups—“young” volunteers who were 18 to 30 years old and “older” volunteers who were 65 to 80 years old—into three different exercise programs where the subjects performed either high-intensity interval biking, strength training with weights, or combined strength training and interval training. Researchers then took biopsies from the volunteers’ thigh muscles and compared the molecular makeup of their muscle cells to samples from sedentary volunteers. The researchers also assessed the volunteers’ amount of lean muscle mass and insulin sensitivity.

They found that while strength training was effective at building muscle mass, high-intensity interval training yielded the biggest benefits at the cellular level. The younger volunteers in the interval training group saw a 49 percent increase in mitochondrial capacity, and the older volunteers saw an even more dramatic 69 percent increase. Interval training also improved volunteers’ insulin sensitivity, which indicates a lower likelihood of developing diabetes. However, interval training was less effective at improving muscle strength, which typically declines with aging.

Applying the Findings

What does this research mean for your clients? “If people have to pick one exercise, I would recommend high-intensity interval training,” suggests Nair, “but I think it would be more beneficial if they could do three to four days of interval training and then a couple days of strength training.” Of course, any exercise is better than no exercise.

Nair stresses that the focus of this study wasn’t on developing recommendations, but rather on understanding how exercise helps at the molecular level. As we age, the energy-generating capacity of our cells’ mitochondria slowly decreases. By comparing proteomic and RNA-sequencing data from people on different exercise programs, the researchers found evidence that exercise encourages the cell to make more RNA copies of genes coding for mitochondrial proteins and proteins responsible for muscle growth. Exercise also appears to boost the ribosomes’ ability to build mitochondrial proteins. The most impressive finding was the increase in muscle protein content. In some cases, the high-intensity biking regimen actually seemed to reverse the age-related decline in mitochondrial function and proteins needed for muscle building (Figure 1).

The high-intensity biking regimen also rejuvenated the volunteers’ ribosomes, which are responsible for producing our cells’ protein building blocks. The researchers also found a robust increase in mitochondrial protein synthesis. An increase in protein content explains enhanced mitochondrial function and muscle hypertrophy. Exercise’s ability to transform these key organelles could explain why exercise benefits our health in so many different ways.

Muscle is somewhat unique because muscle cells divide only rarely. Like brain and heart cells, muscle cells wear out and aren’t easily replaced. Functions in all three of those tissues are known to decline with age.

“Unlike liver [tissue], muscle is not readily regrown. The cells can accumulate a lot of damage,” Nair explains. However, if exercise restores or prevents the deterioration of mitochondria and ribosomes in muscle cells, there’s a good chance it does so in other tissues, too. Understanding the pathways that exercise uses to work its magic may make aging more targetable.

Research On the Horizon

Nair and his colleagues hope to find out more about how exercise benefits different tissues throughout the body. They are also looking into ways that clinicians may be able to target the pathways that confer the most benefits. For the time being, however, vigorous exercise remains the most effective way to bolster health.

“There are substantial basic science data to support the idea that exercise is critically important to prevent or delay aging,” says Nair. “There's no substitute for that.”

More Articles

- Certified™: May 2017

ACE-SPONSORED RESEARCH: Is Zumba Gold® an Effective Workout for Middle-aged and Older Adults?

- Certified™: May 2017

Beast Battle Ropes: An ACE Integrated Fitness Training® Model-based Workout

Health and Fitness Expert

- Certified™: May 2017

The Latest Tools of the Trade: The Mace by Onnit

Health and Fitness Expert

- Certified™: May 2017

Social Media: A Simplified, Less-is-more Approach

Health and Fitness Expert