|

Key Takeaways The importance of strength training for seniors in terms of expanding longevity, healthspan and strengthspan cannot be overstated. In addition to covering the connections between sarcopenia and overall wellness and explaining exactly why muscle mass declines with age, this blog provides practical exercise programming guidelines, along with a sample full-body workout that can be tailored to align with your clients’ goals, abilities and experience. Read on to learn everything you need to know to help clients get started with a safe and effective workout that will make them feel stronger, healthier and more independent as they grow older. |

As all health coaches and exercise professionals know, exercise is vital for living a long, healthy life. Few things have a greater impact on a person’s longevity, or how long they live. Two recent ACE blogs looked at healthspan (the number of years a person can live without chronic or debilitating disease) and strengthspan (a measure of physical strength over a lifespan, which directly relates to the ability to function independently and move safely as we age). Healthspan and strengthspan define not how long we live, but how well.

Strength training can pay huge dividends later in life in terms of expanding not only longevity, but also healthspan and strengthspan—and the earlier a person gets started, the better. So many age-related concerns that impact quality of life, from balance and grip strength to osteoporosis and sarcopenia, can be countered by building muscular strength and function early in life and then maintaining it as we grow older. That said, it’s never too late to get started and reap the benefits of strength training.

Sarcopenia and Overall Wellness

This blog focuses on sarcopenia, which is defined as an age-related decline in muscle mass, strength and performance.

Muscle strength and mass increase from birth until they reach their peak around the age of 30 to 35 years old. After this time, muscle performance and power begin to decline at a slow and gradual pace until the age of 70 for men and 65 for women, at which point the rates decline more rapidly. In total, this can lead to ~50% loss in mass by the time a person reaches their eighth or ninth decade of life. In addition, muscle function is lost at a rate of about 2.5 to 3% per year in women and 3 to 4% in men beginning at about age 75.

|

Why Muscle Mass Declines with Age Sarcopenia is related to the following underlying pathophysiology:

|

Some clients may wonder why muscular strength is so important. After all, how strong do we really need to be when we get older? The truth is, sarcopenia is most problematic because it is associated with an increased risk for many adverse health outcomes, such as hospitalization, functional decline, higher rates of falls, chronic disease, nursing home admissions, increased healthcare costs and even mortality.

Of course, aging is a process that is going to take place no matter what. The good news is that, unlike aging, physical activity is a variable that can be changed. In fact, declines in strength and power that occur with aging can be substantially slowed down by leading and maintaining an active lifestyle. Unfortunately, only about 14% of older adults (65 and older) meet physical activity guidelines for both aerobic and muscle-strengthening activity.

Exercise Programming for Older Adults

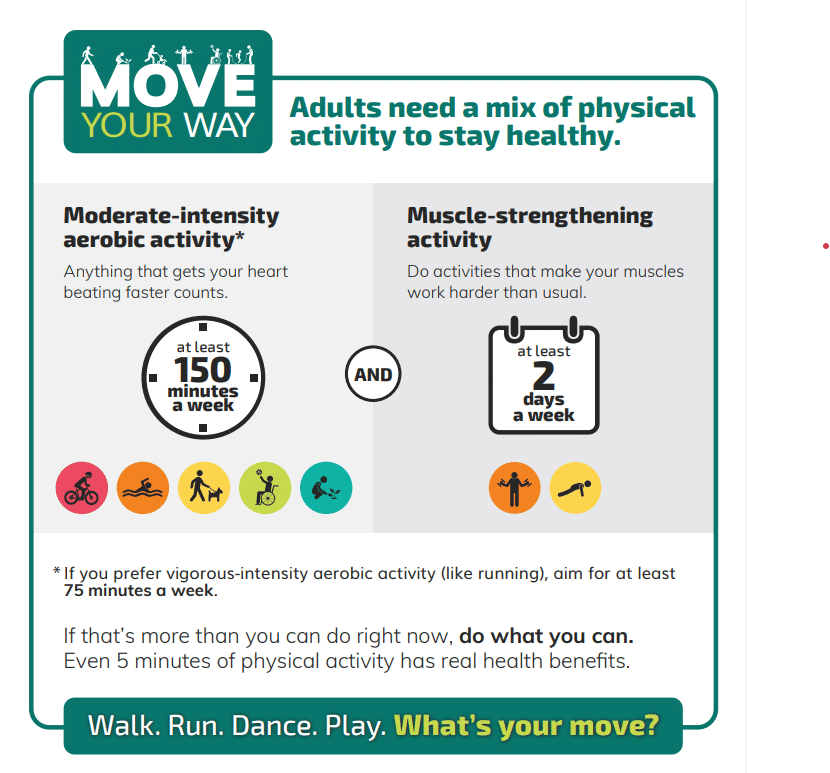

All adults, regardless of age, need a mix of physical activity to stay healthy. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans are clear that older adults should participate in multicomponent physical activity that includes muscle-strengthening activities, aerobic exercise and balance training. Engaging in activities that build muscular strength is recommended on at least two days per week.

Reprinted from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2018). Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd ed.

According to recent expert consensus guidelines, adhering to the following exercise program design recommendations will maximize both musculoskeletal system adaptations and time-efficiency. Note that selecting exercises that directly stimulate muscles involved in activities of daily living, such as step ups and bend-and-lift patterns, may be especially helpful for this population.

Exercise Recommendations

| Frequency | 2–3 times per week, with a minimum of one day of recovery between sessions targeting the same muscle group |

| Intensity |

50–80% 1-RM |

| Time | 1–3 sets of 8–12 repetitions (begin with 1–2 sets and progress to 2–3 sets) |

| Type |

6–10 exercises, including both multijoint and single-joint exercises |

Note: 1-RM + One-repetition maximum

Sample Full-body Workout for Older Adults

Using the guidelines presented above, complete this workout by moving from left to right and starting back at the beginning for the desired number of sets (one to three). The seven exercises in each row constitute a full-body workout, so you can complete the same row multiple times or flow from one row to the next.

If you are performing strength training three times per week, another good option that offers variety is to use each row as a workout and perform the desired number of sets.

Final Thoughts

Strength training offers tremendous benefits at any age and the rewards build up over time, so starting early and being consistent will leave clients much better positioned to enjoy an independent and active lifestyle later in life. That said, it’s never too late to start. Encourage clients to begin slowly, with one set of eight to 12 repetitions of each exercise twice per week and progress from there. They may be surprised how quickly they start to feel stronger and more capable of performing day-to-day activities.

|

If you’re interested in exploring the importance of health and exercise and creating appropriate programming for the aging population, check out The Science of Programming for Older Adults (worth 0.1 ACE CECs). In this course, you’ll learn how to recognize cardiovascular and strength-related changes associated with aging and gain a new perspective on the unique needs of the older adult population. |

by

by

by

by