By FABIO COMANA, M.A., M.S.

While many top-tier teams suffered the fate of an early exit in the World Cup 2010, this quadrennial event continues to provide a significant boost to the world’s most popular sport. In the U.S. alone, our expanded media coverage of international football, Major League Soccer (MLS) with its international superstars, and a regular schedule of international matches played on U.S. soil have all helped to dramatically increase the popularity of this game, especially amongst the ranks of our youth. So, with soccer fever still running high and athletes gearing up for the fall soccer season, there has never been a better time for trainers and coaches to market their soccer-specific training programs.

Given this sport’s relative infancy in the U.S., it is fair to assume that some trainers and coaches may feel they lack the appropriate levels of soccer exposure or experience to prepare athletes for this game effectively. As a conditioning coach, never let this limit your ability to accept the challenge of training athletes for this or any other sport. As with most competitive sports, soccer athletes typically work with two or more coaches. The team or sport coach develops and trains the technical elements and implements competitive strategies, while the conditioning coach prepares the athlete physiologically and psychologically to perform at optimal levels. The following article demonstrates how a conditioning coach with an extensive knowledge of exercise science, who knows how to conduct a comprehensive needs assessment of both the sport and the athlete(s), can design successful training programs for soccer athletes.

Step One: Conduct a Needs Assessment

- Watch the sport, take notes, film the sport and ask questions.

- Gain exposure and understanding of the sport and its rules by watching higher-level practices (top tier universities if possible) and international matches.

- Focus your attention to your athlete’s position (if training one individual).

- Never miss the opportunity to gather information by interviewing top-level coaches and athletes.

- Using a stopwatch, calculate the average work-to-recovery ratios for each specific position throughout an entire game.

- FIFA’s (soccer’s governing body) standards for field dimensions require a field of play measuring up to 120 yards (110 m) long x 80 yards (75 m) wide. This is far larger than the NFL’s field of play, which measures 100 yards (90 m) long x 53.3 yards (48 m) wide.

- Each team fields 11 positional players who are aligned in different formations (e.g., 1-4-4-2, 1-4-3-3, 1-5-4-1), but constantly move up and down the field throughout a 90-minute regulation game.

- Given the large field dimensions and duration of a regulation game, many believe soccer is primarily an aerobic sport, when in fact it is not.

- A study published in the Journal of Sports Science and Medicine in 2007 by Barros et al. measured the distances covered during a 90-minute regulation game using 55 top-level Brazilian soccer players. Results indicated an average of 10,012 m (11,122 yards or 6.3 miles) covered, of which 56.3 percent was spent walking or jogging; 17.2 percent was spent in low-speed running; 18.4 percent was spent in moderate-speed running; and 8.1 percent was spent in all-out sprinting.

- However, it is the constant stop-and-start nature (change of intensity) of the game that renders it primarily anaerobic. Ten percent to 20 percent of the volume of work performed during a game utilizes the phosphagen system, 60 percent to 70 percent utilizes the fast glycolytic system, leaving 20 percent to 30 percent of the volume of work performed to rely upon the oxidative pathway.

- Examine the movement patterns performed by position (e.g., jumping to head a ball, dribbling, cutting, curving) and your athlete’s strengths and weaknesses in comparison to what is needed to be successful (i.e., based on information gathered from interviews and from your own deductions).

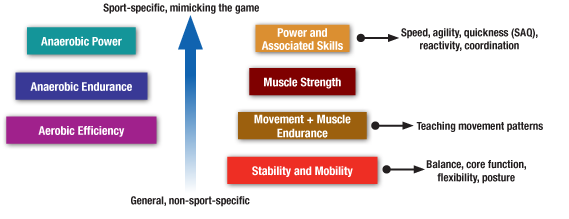

- Identify the health- and skill-related parameters of fitness you will need to train to improve performance, and sequence how you plan to address each one (Figure 1).

- Talk to medical staff to identify prevalent injuries as your program should target strengthening or stretching areas that are susceptible to injury. Outside of superficial lacerations and bruising from incidental contact, lateral ankle sprains and knee injuries are probably the most significant.

- Identify what sport-psychology strategies are appropriate for your athlete(s). If necessary, consult with a professional trained in sports psychology.

Figure 1: Required Health- and Skill-related Parameters for Soccer

- As discussed in the ACE Personal Trainer Manual (4th ed.), knee instability is strongly influenced by the position of the ankle and the lack of postural and lateral hip muscle action (e.g., gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, hamstrings).

Step Two: Conduct Relevant Assessments

The ACE Integrated Fitness TrainingTM (ACE IFTTM) Model offers both functional and physiological assessments. Considering the variety of fitness parameters that need to be addressed, select assessments that are relevant with respect to timing and training objective. Your initial assessments should focus upon posture and foundational movement efficiency (stability-mobility relationship) and the foundational elements of balance and aerobic efficiency (Ventilatory Threshold One or VT1). Your selection of future assessments should quantify the sport- and skill-specific parameters needed for success in soccer using protocols offered within the ACE IFT Model or you may elect to design your own soccer-specific tests that mimic many of the key activities, intensities and durations performed during a game:

- Anaerobic endurance or capacity (e.g., VT2-HR test, 300-yard shuttle test)

- Muscular fitness (e.g., lower-extremity endurance or strength)

- Power (e.g., vertical jump, heavy medicine ball toss)

- Speed (e.g., 40-yard dash)

- Quickness and agility (e.g., pro-agility drill, stop-and-start drill)

- Evaluate both time and success in completing a circuit of multi-directional stop-and-starts with directional changes, interspersed with explosive jumps (headers), get-up and go’s (fall to ground, explode back to feet to pursue), and precise kicks of varying distances to targets within a specified time-period that resembles the average work intervals observed during a game.

Step Three: Establish Goals and Design your Program

With consent from your athlete (if applicable), involve the relevant and appropriate individuals (e.g., parents, coaches) to collectively establish goals based upon identified needs, strengths and weaknesses. During this phase, it is also important to develop your training macrocycle or overall template for the training program. As a university-level strength coach, I employed an effective technique of outlining for the entire year the athlete or team’s week-by-week schedule, and factored in all potential “blackout” periods. These included practice and game schedules, school schedule conflicts (e.g., exam schedules, spring breaks), work, vacation and family commitments, and any other potential obstacles that may interrupt a systematic approach to training progression. Your program can then be bundled and sold as distinct training mesocycles, each aimed at specific objectives along the ACE IFT continuum that ultimately progress to the Performance and Anaerobic Power mesocycles needed for soccer.

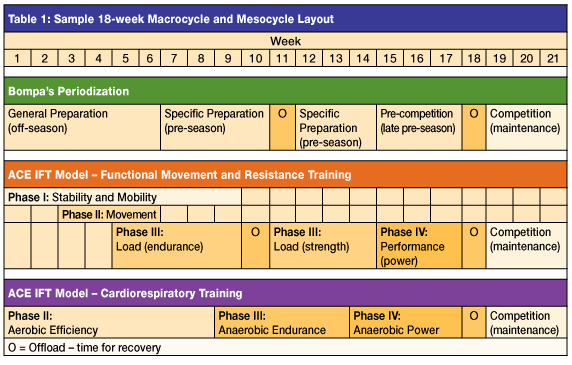

Traditional periodization models incorporate specific training phases that systematically prepare the athlete for their competitive season. For example, Bompa’s periodization model includes Preparatory, Competitive and Transition phases, each aiming to achieve unique objectives that tend to coincide nicely with the training phases of the ACE IFT Model (Table 1).

ACE IFT Model: Four Phases of Functional Movement and Resistance Training

Phase I: Stability and Mobility

- Soccer is essentially a closed-kinetic-chain, multi-joint and multi-planar dynamic sport where the body continuously generates forces (unload), withstands the effects of gravity (stabilize) and tolerates all reactive forces (load) to achieve movement success.

- As all movement begins and ends from a position of static posture, it makes sense to first develop one’s movement platform; this includes the appropriate levels of stability and mobility, not just across individual joints, but also throughout the kinetic chain (implies balanced muscle function).

- Joints lacking appropriate levels of mobility force compensation within the more stable joints, which in turn promotes dysfunctional movement and increased injury potential.

- Hence, your first objective is to re-establish muscle balance and this stability-mobility relationship, which entails:

- Promoting proximal stability first (core function and static balance) that then facilitates more distal mobility.

- Restoring normal neural and physiological function within the tightened and weakened muscles to promote proper movement mechanics.

Phase II: Movement

- Using the information gathered from your movement screens, devise a systematic approach to training movement.

- Step One: Build a static base of support by improving the mechanics of performing the primary movement patterns (bend-and-lift, single-leg, pushing, pulling and rotational).

- Step Two: Add dynamic drivers to the primary movement patterns (i.e., driving the upper extremity and body 3-dimensionally) to increase body load.

- Step Three: Introduce dynamic movement patterns using the following guidelines:

- Implement high-volume/low-intensity drills for skill acquisition (move from cognitive stage to the associative stage of motor learning).

- Uni-planar movements precede multi-planar movements.

- Forward-linear movements precede lateral movements, which in turn precede backward and rotational movements (i.e., dribbling, turning, curving, cutting).

Phase III: Load

- The quantity of muscle overload selected for endurance, strength and maximal strength is derived from the needs assessment of your athlete(s).

- While muscle endurance serves to build a foundational platform to sustain 90 minutes or more of continual muscle action, it is strength and maximal strength training that are vital to the development of power in soccer.

- Your training programs should initially follow a linear periodization model, then transition to undulating or non-linear periodization models when your athlete’s body is adequately prepared.

Phase IV: Performance

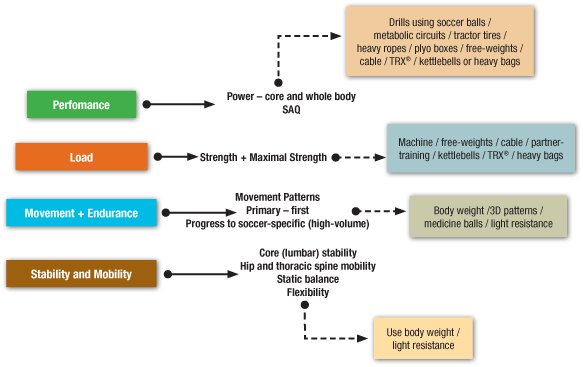

- As illustrated below, this phase involves various training tools and modalities that enable execution of explosive movements.

- Advanced plyometric drills (e.g., multi-directional jumps, bounds and hops, depth jumps), built upon a foundation of strength are an integral component to this phase of training.

- Utilize high work-rate metabolic circuits to mimic the workloads and durations of a game.

Figure 2 illustrates various activity options for the four phases of functional movement and resistance training.

Figure 2: Training Soccer Athletes using the ACE IFT Model for Functional Movement and Resistance Training

ACE IFT Model: Three Phases of Cardiorespiratory Training

[Note: Phase I is not included here because soccer athletes have an established aerobic fitness base.]

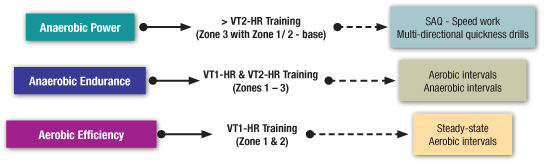

Phase II: Developing Aerobic Efficiency

- After assessing VT1, develop four- to six-week microcycles, each aimed at progressing the heart rate (HR) at which VT1 is achieved (VT1-HR), moving it progressively into higher intensities.

- This implies increased aerobic efficiency or the ability to sustain greater fat utilization at higher exercise intensities, sparing potential glycogen depletion while improving recovery rates (the more quickly one switches to aerobic systems during recovery, the faster the anaerobic pathways recover).

- Using the ACE IFT Model, this phase incorporates training in Zone 1 and lower regions of Zone 2 (steady-state or aerobic interval-training, emphasizing volume over intensity) and may run six to 20 weeks.

- During this phase, coaches should also include a high volume of low-intensity drills to develop skills (technique) for speed, agility and quickness (SAQ).

Phase III: Developing Anaerobic Endurance

- Progress to Phase III after making notable improvements in increasing VT1-HR.

- Assess VT2-HR for your Phase III training program, which aims to enhance your athlete’s capacity for higher-intensity bouts of work (building anaerobic endurance).

- This implies improved capacity to tolerate and clear accumulating lactate and sustain higher intensities of exercise.

- Using the ACE IFT Model, this phase incorporates training in the higher regions of Zone 2 with specific intervals into Zone 3 (>VT2-HR), employing work-to-recovery ratios that push VT2-HR higher.

- For example, performing 15- to 30-second work intervals at 75–90% of maximal effort with a 1:3–5 active recovery ratio (15 seconds of work + 45–75 seconds of active recovery).

- This phase builds upon the SAQ skills and increases work rate, and may run nine to 12 weeks.

Phase IV: Developing Anaerobic Power

- As VT2-HR plateaus, shift your focus to peaking SAQ, drawing primarily upon the phosphagen energy system with bouts performed at 90–100% of maximal effort.

- Quickness drills train explosiveness for stop-and start actions.

- Agility drills train foot speed for acceleration and directional change.

- Both are trained best using drills <5–7 yards in length between markers.

- Speed drills improve velocity and are best trained with drills >10 yards.

- Using the ACE IFT Model, this phase incorporates short-duration, very-high-intensity drills employing work-to-recovery ratios to improve the efficacy of the phosphagen energy system.

- For example, performing 5-second work intervals at 90–100 % of maximal effort with a 1:12–20 passive recovery ratio (5 seconds of sprint work + 60–100 seconds of passive recovery).

- While much of the training volume (time) of this stage may be spent in Zones 1 and 2 (recovery), it is the short, very-high-intensity bouts of soccer-specific speed work and quickness training that makes this phase of training very challenging.

- Consequently, this phase should run six to eight weeks, training two to three times per week to allow for adequate glycogen and muscle recovery.

- During this phase, add external resistance modalities to increase work intensity (e.g., partner resistance, sleds, chutes).

Figure 3 provides various activity options for Phases II–IV of Cardiorespiratory Training.

Figure 3: Training the Soccer Athlete using the ACE IFT Model for Cardiorespiratory Training

Additional Performance Variables to Consider

Mental skills training is an integral part of training, whether for individual or team sports. Coaches should identify the optimal levels of arousal needed by their athlete(s) to maximize performance (maximize attentional focus and performance). Performance depends in part upon an athlete’s decision-making process and response selection, both of which are affected by levels of arousal and anxiety.

- Arousal defines a state of responsiveness to sensory stimulation or excitability and measures anticipation within the central nervous system

- Anxietydefines a person’s uneasiness or distress regarding future uncertainties or the perception of threat to one’s self.

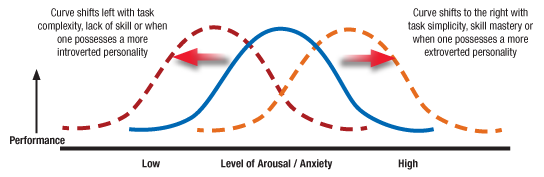

- The Yerkes-Dodson Inverted-U Curve examines the relationship of these traits to performance (Figure 4).

- Moderate levels of arousal and anxiety promote better performance, whereas insufficient or excessive levels prove distracting and detrimental.

- Every individual has a unique curve based upon his or her own personality traits, skill-level and complexity of tasks performed.

Figure 4: Inverted-U Curve

Utilize a variety of effective mental-skill strategies, including mental imagery, power (mood) words/phrases, progressive relaxation and breathing techniques, and methods to improve cue utilization (differentiating between relevant and irrelevant cues) to help the athlete mentally prepare prior to a training session or competition.

Conclusion

Soccer is a complex sport that requires a multi-faceted training approach to maximize both cardiorespiratory (aerobic and anaerobic) performance, as well as speed, power and quickness. This necessitates a systematic approach to training that builds upon a solid foundation, then progresses toward optimal athletic performance. The ACE IFT Model offers such an approach, which can help you deliver effective performance-based results for soccer athletes. Take the ACE IFT Model for a test drive and realize what an impact and difference it can make to the success of your programs. To learn more about the ACE IFT Model, refer to the ACE Personal Trainer Manual, 4th Edition.

_____________________________________________________________

Fabio Comana, M.A., M.S., is an exercise physiologist and spokesperson for the American Council on Exercise, and faculty at San Diego State University (SDSU) and the University of California San Diego (UCSD), teaching courses in exercise science and nutrition. He holds two master’s degrees, one in exercise physiology and one in nutrition, as well as certifications through ACE, ACSM, NSCA, and ISSN.