By FABIO COMANA, M.S., M.A.

While tennis may be considered a second-tier sport in the U.S., it is actually the fastest-growing sport in America among individual, traditional sports. In fact, according to the Sporting Goods Manufacturers Association, tennis was one of only six sports to experience participation growth exceeding 40 percent between 2000 and 2008, placing its growth ahead of other traditional sports like baseball, ice hockey, gymnastics and football. In 2008 alone, tennis experienced a 9.6 percent increase in participation, with an estimated 18.6 million people, ages six and older, playing tennis on a regular basis (SGMA, 2008).

Part of this sport’s success can be traced to various effective “on-boarding” programs designed to begin a developmental pathway to what is considered a lifelong sport. Programs like QuickStart Tennis for young players, the United States Tennis Association’s (USTA) No-Cut and Tennis on Campus programs for high-school and college-aged individuals, and newer fitness-based Cardio Tennis for adults that combines tennis with a healthy and fun workout curriculum, have put the tennis industry at the forefront of engaging and retaining players once they get started. The USTA has helped shed the sport’s country-club image and implemented a more community-based approach to expand accessibility. Additionally, modifications to the traditional game now make it easier to learn and master the sport, using a progressive system of court sizes, different balls and rackets to scale down the game and allow individuals of all ages and skills the opportunity to participate.

While tennis provides numerous health benefits—improved aerobic fitness and anaerobic endurance, muscular fitness (grip strength and endurance), flexibility, multiple skill parameters (balance, speed, agility and quickness), reactivity, and power—it also is psychologically demanding. Generally, it is a sport that requires hard work and dedication to train these multiple physical skills while also developing many other cognitive abilities (e.g., anticipation, eye-hand coordination, attentional focus), personality traits and social skills (e.g., discipline, camaraderie, patience). These benefits naturally make tennis the ideal sport for children to learn early in life to facilitate the development of both physical and mental skills.

So, with spring just around the corner, why not add another dimension to your training services by using the ACE Integrated Fitness TrainingTM (ACE IFTTM) Model to help the tennis enthusiasts or competitors in your facility achieve their conditioning goals in preparation for the upcoming outdoor tennis season.

Needs Assessment

As with any sport, designing a conditioning program for tennis first requires completion of a comprehensive needs assessment to identify:

- The needs of the sport (energy systems, physical fitness parameters, movement patterns, planes of movement)

- The prevalent injuries within the sport

- The strengths and weaknesses of the individual(s)

- Appropriate mental-skills training strategies

At higher levels of play, tennis is predominantly an anaerobic sport involving a series of high-intensity, multi-directional, stop-and-start bouts of activity coupled with more moderate, sustained rallies performed on a 13-yard x 9-yard (11.8 m x 8.2 m) area (singles courtsize). The dynamic nature of the activity, however, will stress all three energy systems within the body (phosphagen, fast glycolytic and oxidative). Tennis involves multidirectional sprinting, stretching, lunging, bounding, swinging, twisting, and stopping-and-starting in all three planes (Table 1). To learn more about these movements, spend time observing higher-level tennis matches and talk to the appropriate individuals (e.g., coaches, professionals).

|

Table 1: Tennis Needs Assessment

|

| Tennis Phase |

Key Energy System |

Key Physical Parameters |

Key Planes |

| Serve |

Phosphagen |

Power, coordination |

Sagittal, transverse |

| Strokes |

Phosphagen |

Power, flexibility, balance

|

Lateral, ransverse |

| Rally |

Aerobic, anaerobic |

SAQ, flexibility, balance |

Lateral, transverse |

| Net Play |

Primarily anaerobic |

SAQ, reactivity, balance

|

Sagittal, lateral

|

Note: SAQ = Speed, Agility, Quickness

Because tennis is repetitive in nature, chronic injuries are a common occurrence, but acute injuries, which are due to sudden forces or impacts, can also be a concern. Holding a brief conversation with a tennis coach or qualified medical practitioner who specializes in tennis or sports injuries can help you identify problematic areas. These typically include:

- Lateral epicondylitis (tennis elbow)

- Bursitis or tendonitis (shoulder, elbow, wrist)

- Osteoarthritis (knee)

- Muscle/joint sprains and strains (ankle, knee and ankles; hamstrings, Achilles tendon, rotator cuffs)

Peter Mattera, San Diego State University’s (SDSU) women’s tennis head coach, says the nature of the injuries his athletes suffer most frequently has evolved over his 19-year tenure. He attributes much of this change to the introduction of strength and conditioning to women's athletics, and to technological advances in the design of sports equipment. SDSU women’s tennis boasts one of the more intense conditioning programs in collegiate tennis. Aerobic and anaerobic conditioning, weight training, movement training, on-court agility drills, plyometrics and several hours every week of one-on-one drilling makes the women’s team among the most well-conditioned in Division I tennis. Due to this increased level of conditioning, he sees few lower-extremity injuries in his athletes, but notes that today’s larger, stiffer racquets transfer more vibration forces into the wrist and shoulders. Consequently, his athletes now experience a greater incidence of wrist and rotator cuff injuries, which may be exacerbated, in part, by the increased upper-extremity strength and power of his athletes.

When Mattera coaches recreational enthusiasts, he emphasizes the enjoyment factor. Part of his needs assessment is to evaluate their desire to play and improve, and to identify the strengths within their skill-sets and abilities. He then lays out a plan to work with those strengths to develop increased sport proficiency that boosts initial enjoyment with the game. For example, he recognizes that for many participants, the ability to sustain a rally is a key enjoyment factor, so he works to help individuals successfully hit the ball over the net before anything else. To achieve this, he focuses on their racquet grip, their ball approach (feet breakdown) and developing a basic, smooth stroke to strike the ball.

Movement and Resistance Training

We all recognize that muscles function to move levers, but we must also understand their role as reactors to the external forces experienced along the entire kinetic chain. We must consider how ground reactive forces, loads, levers (e.g., racquet) and momentum affect both individual segments and the entire kinetic chain. Failure to examine the integrated nature of tennis movements will certainly predispose one to a variety of movement compensations (dyskinesis), musculoskeletal overload and, ultimately, a breakdown or injury. This requires the fitness professional to examine the stability-mobility relationship within the kinetic chain, much the way an engineer must examine the foundation of a building before attempting to make any structural changes. An understanding of this relationship unlocks the keys to promoting movement efficiency and improvement, whether it is part of your session’s dynamic warm-up or the individual mesocycle goals within your overall program (see “Understanding the Stability-mobility Relationship of the Kinetic Chain”).

1. Training for Stability and Mobility

Understanding the Stability-mobility Relationship of the Kinetic Chain

Application

- Stand with feet slightly wider than hip-width apart.

- Reach your right arm across the left side of your body as if throwing a “cross.”

- Repeat to the opposite side with the left arm.

- Perform several repetitions in each direction.

- Repeat these movements, but this time, restrict any movement from your ankle joint. Notice the difference in quality of movement (i.e., how far is your reach)?

- Repeat these movements, but now restrict any movement from your ankles and hips. Notice the difference in quality of movement (i.e., how far is your reach)?

- This illustrates how the mobile joints and the integrated chain all contribute to promote quality of movement.

Remember, when a joint lacks mobility, the body compensates by seeking the desired movement from adjacent, more-stable joints.This compromises that joint’s stability and exposes it to potential injury.

Never compromise stability within a joint.

Balance is a critical foundation to training a tennis player and begins early in your programming. Given the jumping (impact), twisting and explosive movements generated in both the lower and upper extremity, promoting effective lumbar stability is crucial for success. Consequently, an important objective of your initial programming should be to optimize lumbar stability and reduce the potential for a low-back injury by first developing effective core function, and progressing toward the concept of “bracing.” (Refer to the ACE Personal Trainer Manual, 4th edition, for more information on training for these goals). The dynamic multi-planar nature of tennis demands exceptional balance or control of the body’s center of mass (COM), while simultaneously possessing excellent mobility to make some impressive reaches while covering the court. Your static balance training should challenge your client to attain those multi-directional drivers (reaches) in both backhand and forehand positions, while maintaining postural (stability) and recovery control (the ability to quickly return to a good base of support and explode in another direction to cover the court).

Some great options to achieve this goal include single-leg stands with multi-directional reaches or training on the CoreTex™ (www.functionfirst.com). This device creates three-dimensional (3D) instability by simultaneously incorporating tilt, translation and rotation into the platform, requiring 3D control of the body during movement. While standing alone on this platform provides a great initial challenge, the athlete should progress to creating tennis-specific movement patterns while demonstrating good postural and recovery control.

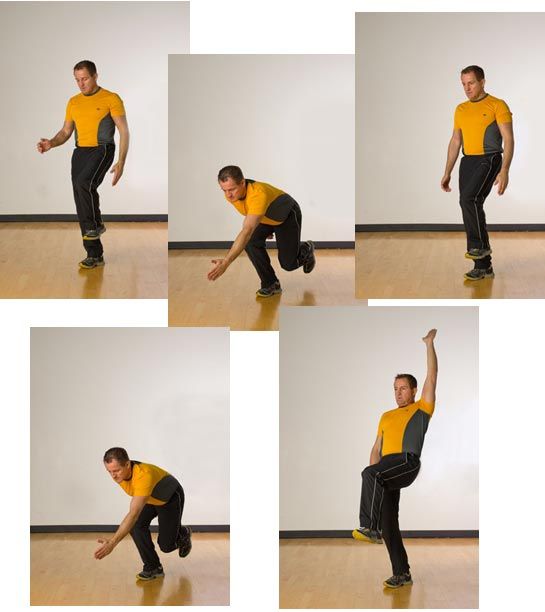

Single Leg Stand with Driver

As your balance-training drills progress toward more dynamic-type drills, aim to mimic the movement patterns exhibited during the game. One simple drill involves placing a cone just outside the doubles lines and having your client walk or jog toward the marker, breaking down their steps and reaching on either one or two legs while simulating a swing movement (forehand or backhand), then recovering back to cover the court. This same drill can be repeated during the performance phase of training, but with speed and power.

Hip mobility and thoracic spine mobility are equally important as lumbar stability. Both allow your client the opportunity to make those lunges and reaches (hip mobility), while helping stabilize the shoulder girdle during the tennis stroke. Success in executing movement within the glenohumeral joint and the associated movement of the scapulae largely depends upon mobility of the thoracic spine. Without this mobility, the scapulothoracic region or lumbar spine sacrifice their respective stability to facilitate the desired movement.

For example, as the glenohumeral joint moves into flexion, the scapula tilts posteriorly 20-40° to accommodate the glenoid fossa and allow the humeral head to move overhead. Consequently, the thoracic spine must extend to accommodate this scapular movement and if it lacks this ability, then (a) the lumbar spine may need to move into hyperextension; or (b) the scapula will have to alter its normal mechanics, resulting in compromised glenohumeral movement and loss of force production.

Below are some exercises that promote hip and thoracic spine mobility. See the ACE Personal Trainer Manual, 4th edition, for more information on each exercise.

Hip mobility:

- Lying hip flexor stretch (pg. 263)

- Half-kneeling tri-planar stretch (pg. 264)

- Lying hamstrings stretch (pg. 265)

Thoracic spine mobility:

- Spinal twists progressions (pg. 268-269)

- Prisoner rotations (pg. 270)

- Thoracic matrix (pg. 301)

Much of one’s success in tennis also depends upon grip strength; grip position and having the appropriate racquet handle grip size. While dynamic and isometric exercises to improve grip strength (hand and forearm strength) should be included, have your client consult with a qualified tennis professional to determine optimal grip size and grip position.

2. Training for Movement Efficiency

The ACE IFT™ Model identifies five primary movement patterns that one should train prior to introducing external loads (Load Training Phase). The goal behind this training phase is to promote movement efficiency prior to external loading and to help avoid attempts by the body to resort to dysfunctional patterns to generate the required force to overcome the external loads. An analysis of many of the movement patterns in tennis reveals that the bend-and-lift, single-leg and rotational movements occur frequently. (Note: The tennis stroke itself can be considered a partial pull-push movement.)

- A modified bend-and-lift is used explosively during serves and during most groundstrokes (mimicking the low-to-high approach coaches favor).

- The single-leg stand is used frequently as one covers the court reaching for shots and includes the progression into a variety of multi-directional lunges to execute ground strokes and volleys.

- Rotational movements occur any time the player strikes the ball, generating power from the hips and transferring it to the trunk and shoulder girdle (e.g., serve, ground strokes and volleys).

Given the degree of skill required to execute a great stroke in tennis, spend time first instructing the proper form (mechanics) of the primary movement, then incorporate planes and drivers (with the trunk, head, arms and swing leg) that mimic the true movements needed or observed during the game. Train your client to perform these with proper form in a slower, controlled manner, before increasing both speed and power (introduced during the performance phase of training). When instructing the lower-extremity movement patterns or adding drivers, follow a simplistic, but logical approach of training sagittal-plane patterns first, followed by frontal-plane movements, and lastly introducing the transverse plane. The inclusion of light loads (2-8 pounds) can prepare the body for future challenges with heavier loads. The ViPR™, for example, is an excellent tool to train the multi-directional lunge/reach patterns from low-to-high.

Lunge with Reach

Rotational movements play a significant role in generating power during the serve and stroke. The hips—not the spine—optimize the potential to generate power; therefore, aim to avoid excessive torques in the spine by utilizing the hip flexors and extensors to initiate the transverse plane forces. This allows the trunk to simply rotate off the hips without compromising lumbar spine stability or producing excessive torques. Instruct the correct rotational movement without external loads, teaching clients to engage the hip flexors to initiate the downward “pull” phase (hip-hinging) and the glutes to initiate the upward “push” phase. Again, this drill can be repeated during the performance phase of training, but with speed and power using external loads.

3. Load Training

Load training can follow either a linear or undulating (non-linear) format that progresses the client from a “generalist” approach toward a more “specialist” format of training. Your decision to include muscle endurance, hypertrophy and strength training should be based on the results of your needs assessment and a comparison of your client’s strengths and weaknesses with the specific demands of tennis.

4. Performance Training

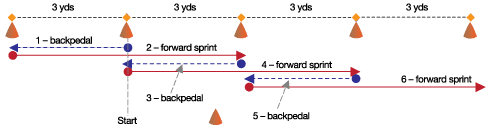

This phase is critical for success in tennis, and the specificity of your drills and exercises must match the movement patterns of the game. Developing SAQ and power should be your areas of focus. To enhance speed, agility and quickness (SAQ), you will need to help your client develop foot speed with agility ladders, cones and hurdles, while also developing quickness (stop-and-start). Given the small dimensions of the court, agility and quickness are more relevant than speed (more linear in nature and usually required to cover greater distances). Regardless of the training drill or equipment used, follow the same plane progression format discussed in the previous section to facilitate learning and skill development (sagittal, frontal, and then transverse). An example of a basic stop-and-start drill is outlined in Figure 1 and can be implemented and modified to train any plane of movement. This drill is considered a closed or pre-determined drill where the client is provided instructions of the movement sequence in advance and can therefore anticipates his or her needs ahead of the drill. In reality, tennis is usually open-skilled or reactionary, meaning a player has to react to the opponent’s stroke. Consequently, this stop-and-start drill can progress to becoming reactive by having the client respond to your visual or verbal cue.

Although the use of tennis-specific drills for quickness is important, lower- and upper-extremity mechanics for acceleration and deceleration (e.g., shoulder drive with a racquet, breakdown approach to the ball) are integral components of success with these types of drills. ACE’s Sports Conditioning Workshop offers practitioners the opportunity to learn more about the mechanics of acceleration and deceleration.

Figure 1: Stop-and-Start: Forward-backward Sprints

Drill instructions:

- Arrange a line of 5–8 cones spaced 5 yards apart.

- Have the client stand at the second cone facing outward (i.e., toward the 3rd cone), and lower her center of mass toward the ground by flexing slightly at the hips and knees (assuming a slight forward trunk inclination).

- On your instruction, the client backpedals (runs backward) toward the 1st cone, breaking down her steps as she nears the cone until one foot aligns with it; she then quickly changes direction and accelerates forward, running toward the 3rd cone.

- The client breaks down her steps to place one foot adjacent to this cone, then quickly changes direction, backpedalling toward the 2nd cone, again breaking down her steps as she nears the cone until one foot aligns with it. She then quickly changes direction and accelerates forward, running toward the 4th cone.

- This stop-and-start motion continues until the client runs through all the cones.

This drill can then be progressed to lateral movement where the client will turn and then run to the left, then change directions and run to the right, mimicking cross-court coverage.

While plyometric drills are an important part of this training phase, never compromise client safety by increasing the risk of an unnecessary injury. Knee injuries, especially in women, are an important consideration when implementing lower-extremity moderate-to-intense plyometric exercises or drills (e.g., multiple jumps, box jumps, depth jumps). Always remember to screen your clients appropriately prior to implementing any higher-intensity drills. One particularly effective lower-extremity prerequisite screen requires the successful completion of five squats in five seconds with 60 percent of body weight while using good form (hip hinging, no valgus/varus movement at the knee). Another useful screen recommended by Jay Dawes, a well-respected strength coach and educator, involves a simple “drop-landing” assessment where clients drop off a 18”–24” box while he observes form and landing mechanics.

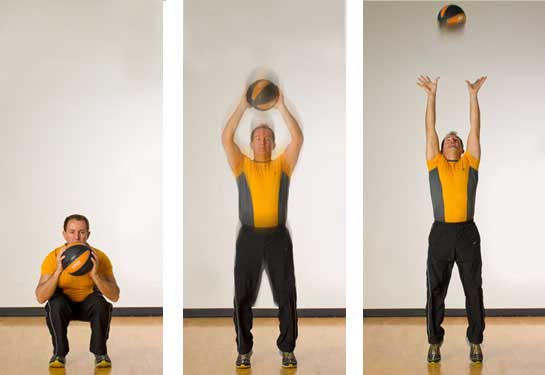

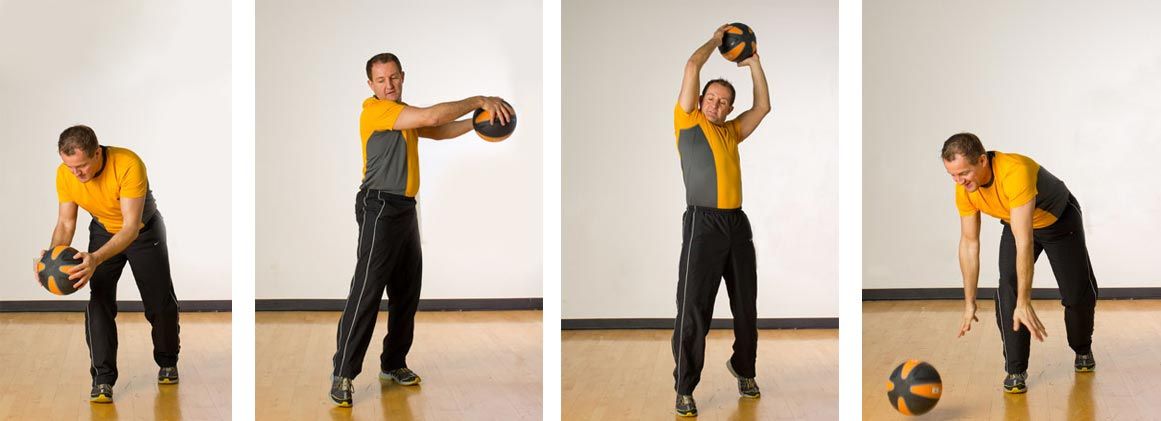

Once your client has been cleared to perform plyometric exercises, you may consider adding the following basic upper- and lower-extremity plyometric drills for the serve:

- For the upward phase: Medicine ball push-press

- For the downward phase: Medicine ball slams (double/single arm)

Medicine Ball Push-Press

Medicine ball slams (double arm)

Medicine ball slams (single arm)

Cardiorespiratory Training

While the stop-start nature of tennis arguably makes it more anaerobic than aerobic, this determination depends more upon the proficiency of the players involved (i.e., at higher levels, the game has a more significant anaerobic component). Regardless, success with developing the fast glycolytic pathways (i.e., lactate system) depends largely upon aerobic efficiency. Developing one’s aerobic efficiency not only affords greater contributions from the oxidative pathways during higher-intensity exercise, but also expands blood volume, which in turn expands the lactate buffer in the blood. This improves the body’s tolerance for greater quantities of lactate to spill over into the blood and increases anaerobic endurance. Additionally, enhancing oxidative capacity also allows athletes to switch back into the oxidative pathways (to metabolize fats) during recovery from high-intensity anaerobic bouts. This facilitates faster reconversion of lactate back to usable forms of energy (e.g., glucose and pyruvate) and greater recovery before the next bout.

Given this information, it is important to first develop aerobic efficiency as a base before targeting anaerobic endurance and anaerobic power. Training to push the first ventilatory threshold (VT1), the body’s metabolic marker of aerobic efficiency, is the most likely starting point for most cardiorespiratory programs for tennis, unless the individual already demonstrates a well-conditioned VT1 score. In reality, the optimal athlete is one who demonstrates a high second ventilatory threshold [VT2, or onset of blood lactate accumulation (OBLA), or what we have come to identify as Lactate Threshold (LT)], but also shows a high VT1 score (ideally where these two markers are within 25–30 beats of each other). Testing the heart rate at which each occurs is an effective way to determine your client’s cardiorespiratory needs and true conditioning level. Developing four- to six-week microcyles using a two-zone model that trains around VT1 with both steady-state and aerobic intervals is an effective way to promote aerobic efficiency. For more information on training to improve VT1, please refer to the ACE Personal Trainer Manual, 4th edition.

After developing your client’s aerobic efficiency, your training focus shifts toward building anaerobic endurance, to push VT2 higher. This enables the client to sustain higher-intensity bouts for longer periods of time. Taking a scientific approach to anaerobic interval training, which includes the appropriate manipulation of your training variables to achieve the desired results, is an effective method to improve anaerobic endurance (Table 2). These variables include frequency (reps), intensity, duration (length of reps), volume (reps x time), and recovery (between bouts).

|

Table 2: Guidelines for Developing Anaerobic Endurance

|

| Energy System |

% of Maximal Power |

Standard Bout Duration * |

Work-to-Recovery Ratios |

Type of Recovery |

| Fast-glycolytic |

75–90% |

15–30 sec |

1:3 to 1:5 |

Active |

|

* Bout duration must ultimately mimic the duration(s) of the bouts needed during a game.

|

Tennis also involves very high bursts of maximal or near maximal efforts for very short periods (e.g., serve, a short rally) that necessitates development of the phosphagen energy system in Phase 4 (Anaerobic Power). Likewise, taking a scientific approach to these intervals is an effective way to improve anaerobic power (Table 3).

|

Table 3: Guidelines for Developing Anaerobic Power

|

| Energy System |

% of Maximal Power |

Standard Bout Duration * |

Work-to-Recovery Ratios |

Type of Recovery |

| Phosphagen |

90–100% |

5–10 sec |

1:12 to 1:20 |

Passive |

|

* Bout duration must ultimately mimic the duration(s) of the bouts needed during a game at this intensity.

|

Conclusion

The ACE IFT Model clearly outlines an effective path to success, but keep in mind that there are numerous psychological and emotional parameters that drive the decision-making process. While we need to challenge our clients to improve so that they may earn the right to progress physically, be sure to identify and understand the drivers behind their behavioral choices, know how to successfully build self-efficacy as you help improve their game, and make sure that they are always enjoying the experience of training with you.

_____________________________________________________________

Fabio Comana, M.A., M.S., is an exercise physiologist and spokesperson for the American Council on Exercise, and an adjunct professor at San Diego State University (SDSU) and the University of California San Diego (UCSD), teaching courses in exercise science and nutrition. He holds two master’s degrees, one in exercise physiology and one in nutrition, as well as certifications through ACE, ACSM, NSCA, and ISSN.