In 2018, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services released an updated version of its Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. This update comes 10 years after the first set of guidelines was released in 2008. The 2008 guidelines were an important turning point in the health and wellness sector, as it was the first time that physical activity was recognized as a way to “reduce the risk of many adverse health outcomes.” This article outlines the updates in the 2018 guidelines and focuses on helping health and exercise professionals understand how to apply these guidelines using the ACE Integrated Fitness Training® (ACE IFT®) Model.

First, let’s review the original 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. This original collection of recommendations came on the heels of the 2007 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, which described what a healthy diet might look like based on nutritional science and consumer needs. In the same way, a team of scientists and health professionals was assembled to create the first Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Their final report concluded that 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week was the minimum amount of exercise (outside of general activities of daily living) required to improve health (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2008). According to the original guidelines, exercise beyond 150 minutes, up to 300 minutes per week, would likely result in further health benefits. For adults, “moderate-intensity physical activity” was defined as walking briskly, water aerobics, bicycling slower than 10 miles per hour, tennis (doubles), ballroom dancing and general gardening (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2008).

The original report also suggested that adults should include regular “muscle-strengthening” activities to obtain even greater benefits for health. The proposed resistance-training suggestions included two days per week of activities that “overload the muscles” and use the large muscle groups (e.g., chest, back, and legs) (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2008).

As a health and exercise professional, it’s easy to see that these recommendations leave much open to interpretation and are geared for the consumer who may not have a concept of different types of moderate-intensity physical activity or muscle-strengthening activities.

While the original set of guidelines aimed to spread the word that physical activity is important, the additional information included in the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans supports the idea that “exercise is medicine.” The new guidelines include the following updates (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018):

- Additional health benefits related to brain health, additional cancer sites and fall-related injuries

- Immediate and longer-term benefits for how people feel, function and sleep

- Further benefits among older adults and people with additional chronic conditions

- Information regarding the risk of sedentary behavior and its relationship with physical activity

- Guidance for preschool children (ages 3-5 years)

- Elimination of the requirement for physical activity for adults to occur in bouts of at least 10 minutes

- Tested strategies that can be used to get the population more active

While the recommended amounts of physical activity (150 minutes per week) and strength exercises (two days per week) remain unchanged, it is important to note that this new report excludes the requirement that physical activity occur in bouts of 10 minutes or more. The 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee, which is made up of scientists from the medical, wellness and fitness fields, determined that any amount of activity is better than none and that even 10-minute bouts may not be doable for a new exerciser. Further, the new guidelines reiterate that additional health benefits, such as reduced cancer risk and unhealthy weight gain, are achieved when activity levels exceed 150 minutes per week. At this time, according to the report, “research has not identified an upper limit of total activity, above which additional health benefits cease to occur” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018).

Physical Activity and Lifestyle Diseases

As a health and exercise professional, you are well-versed in the numerous benefits of regular physical activity. However, it is important to realize that many of these benefits directly relate to a decrease in lifestyle diseases—the chronic conditions related to poor health behaviors.

According to the newly published guidelines, these benefits go beyond reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease (including heart disease, which is the leading cause of death in the U.S.), and specifically highlights advantages to physical activity such as improved sleep, reduced risk of falling and enhanced brain health. These updated guidelines show the results of research that demonstrate that cognition, quality of life, depression, anxiety and sleep are all positively impacted by regular activity (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018). This effect on the brain has, in turn, a direct effect on the rest of the body’s systems. So, by helping clients engage in physical activity on a regular basis to meet the minimum 150 minutes per week, you're not only reducing their risk for some cancers, but you're also helping them to sleep better and feel better in their daily lives.

Putting the New Guidelines Into Practice

What do these new guidelines mean to you, the health and exercise professional? You may feel that these guidelines seem arbitrary or that they seem so general that they’re not worth applying in your practice. However, when applied within the ACE IFT Model, these guidelines are a great resource for you and your clients, especially for those who may be at the beginning of their journey to better health and wellness.

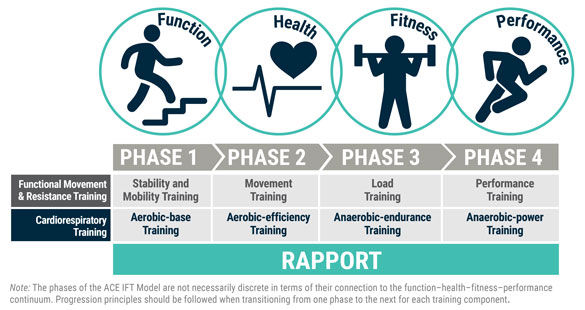

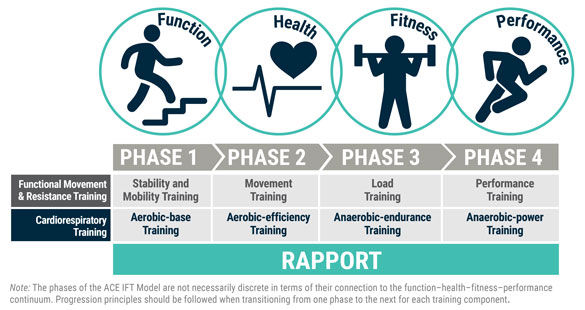

The ACE IFT Model features a foundation of rapport and two training components: “Functional Movement and Resistance Training” and “Cardiorespiratory Training” (Figure 1). For new clients, in particular, who may benefit from using these governmental guidelines as a starting point, the foundation of rapport should not be overlooked. For a new behavior to become a lifestyle change, building a trusting relationship with your clients is essential. A healthy relationship based in understanding and open communication as you work with your clients to achieve their goals will go a long way in setting them up for success in their journey. It will also aid you in creating a successful business. To learn more about building rapport and using behavior-change strategies as you work with your clients, check out ACE’s Behavior Change Specialist program.

Figure 1. ACE IFT Model

Applying the Guidelines to the Cardiorespiratory Training Component

As you begin to apply the guidelines to the Cardiorespiratory Training component, keep in mind that the minimum 10-minute bout requirement no longer applies. If a total of 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity is suggested per week, there are several ways to break that down for a new client using the ACE IFT Model. The Cardiorespiratory component includes four phases. It is likely that a new client will be beginning his or her journey within phases 1 or 2 (aerobic-base training and aerobic-endurance training, respectively). In phase 1, it is important that the client be able to maintain a conversation (learn more about the talk test here). A five- to 10-minute walk, either inside on a treadmill or outside if the weather allows, is a great place to start a new client. It can serve as an informal assessment as you gather information about the client in your first session together, as well as a general warm-up for other assessments or activities to come. If you’re meeting with this client once per week, you may start by working with the client to see if this five- to 10-minute walk is something that could be implemented a few times per day (maybe once per day to start) to promote activity between your scheduled sessions.

It is important to use your rapport-building and behavior-change skills during these first few weeks to work with the client as he or she makes small, incremental changes by getting in those daily walks. Statements such as, “I see you’ve been getting in your walk after breakfast every day—that’s great!” and “It sounds like it’s difficult for you to get your walk in after lunch while you’re at work. Would you mind if I shared a few tips on how to get more activity in during your regular work day?” can serve as motivation while also letting the client know that changing behavior is difficult, and you understand the struggle. When a client is able to maintain a regular walking routine between sessions with you and has built up to 150 minutes per week (which may take one to two months of consistent effort), he or she is ready to move beyond a walking protocol to include other types of activity. This may be the time to begin with other forms of cardiovascular activity and also strength training, as the guidelines suggest.

This is where phase 2 of the Cardiorespiratory Training component comes in. Before moving into this phase, the client should be able to complete 20 to 30 minutes of sustained activity. When transitioning into phase 2, the client should still be able to talk with you during cardiorespiratory activity; however, it should feel a bit more challenging. You can choose to use your weekly training session(s) to include some light intervals as a way to introduce more moderate-intensity activity. An easy way to start is by having the client go back to the 5- to 10-minute walk, remind the client what that used to feel like (build on his or her self-efficacy) and then introduce a short interval (with permission) to elevate the client’s heart rate and respiration rate. Use the submaximal talk-test protocol to ensure that the client is staying right around zone 2, where he or she is still able to have a conversation, yet it feels somewhat more difficult to speak in full sentences.

The client should continue to follow a walking program during the week. However, at this point, he or she may be interested in trying other forms of cardio, such as biking, jogging, hiking or swimming. Encourage the client to try new activities and determine what he or she enjoys, which will help this (still) new behavior stick around for the long-term. If the client is interested in enhancing his or her fitness and progressing into phases 3 and 4 of the Cardiorespiratory Training component, Table 1 shows examples of how this may be accomplished.

Table 1. Cardiorespiratory Training

|

Weeks 1-4

|

Weeks 4-8

|

Weeks 9-12

|

Weeks 13-16

|

|

Phase 1 – aerobic base

|

Phase 2 – aerobic efficiency

|

Phase 3 – anerobic endurance

|

Phase 4 – performance

|

|

Build up to 150 minutes/week

|

Maintain 30 minutes/day activity and begin including short, moderate intervals

|

Maintain daily physical activity with longer intervals at higher intensity

|

Maintain daily activity of 30-60 minutes with active recovery; include 1-2 days of high-intensity intervals

|

|

Below VT1

|

At or below VT1

|

At or below VT2

|

At or above VT2

|

Applying the Guidelines to the Functional Movement and Resistance Training Component

As for applying the new guidelines to the Functional Movement and Resistance Training (FMRT) component of the ACE IFT Model, little direction is offered. To meet the 2018 recommendations of performing at least two days per week of “muscle-strengthening” activities using large muscle groups, let’s start with Phase 1. In the FMRT component, the idea is be sure the client has established effective stability and mobility prior to training movement patterns and before adding additional load and progressing to performance-related activities such as plyometrics. Body-weight movements that stem from the five primary movement patterns presented in the ACE IFT Model are ideal for new exercisers. Table 2 includes sample exercises you may consider using with your client in week 1, first with you in a training session and again as a “homework” workout before or after a daily walk. The table also includes information on how to progress the client’s program over a three-month period.

Keep in mind that this table is an example of how to progress between the phases of the ACE IFT Model within the FMRT component. There are literally thousands of exercises that might make better sense for your client, so use your judgement as a health and exercise professional when programming, especially for clients who may need modifications due to disabilities and pain.

Table 2. Functional Movement and Resistance Training

The 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans contains a wealth of great information for the average consumer and is a helpful starting point for exercise programming for the health and exercise professional. By integrating the guidelines with the ACE IFT Model, including aspects of behavior change, you can use this tool to progress your clients safely along their journey to better health.

by

by