When I was in college, I was diagnosed with chondromalacia and patellofemoral syndrome. Patellofemoral syndrome is a general term for pain on the anterior side of the knee and can have various causes. It’s also quite common, especially in women. At the time, I was also in an athletic training class learning about the Q-angle and the affect it can have on the knees.

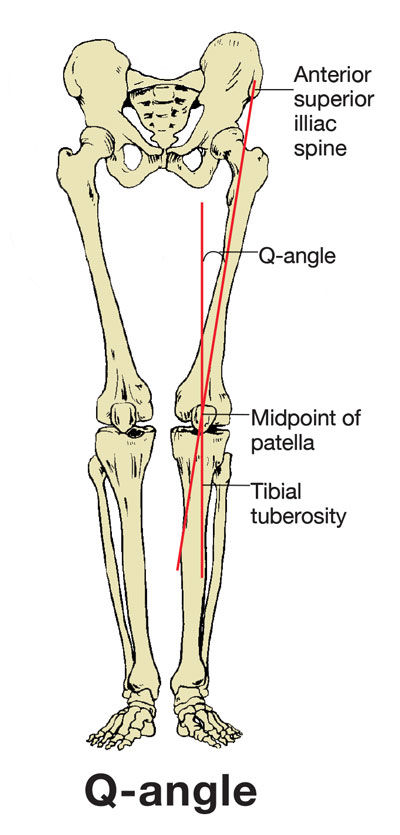

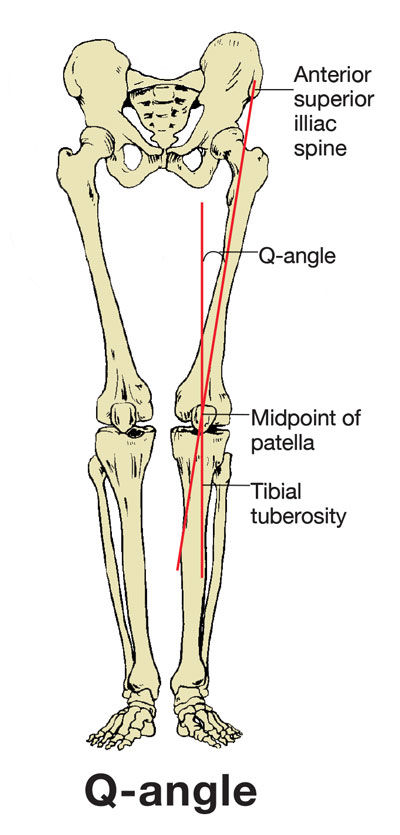

What is the Q-angle? “The Q-angle is calculated by drawing a line from your hip to your knee, and another line from your knee through your shin,” explains Scott K. Lynn, PhD, associate professor of clinical exercise science at California State University, Fullerton. “This Q-angle can be valgus—knock-kneed—or varus—bowlegged."

What is the Q-angle? “The Q-angle is calculated by drawing a line from your hip to your knee, and another line from your knee through your shin,” explains Scott K. Lynn, PhD, associate professor of clinical exercise science at California State University, Fullerton. “This Q-angle can be valgus—knock-kneed—or varus—bowlegged."

The Q-angle is now accepted as an important factor in assessing knee joint function, according to Raveendranath et al. “An increase in Q-angle beyond the normal range is considered as indicative of extensor mechanism misalignment,” write the authors, who studied the variability of the Q-angle in adults in India, “and has been associated with patellofemoral pain syndrome, knee joint hypermobility and patellar instability.”

Simply put, the Q-angle describes the relationship between the hip and knee position in the frontal plane, explains Jessalynn Adam, MD, a sports medicine physician at Mercy Orthopedic Specialty Hospital in Maryland. Additionally, Adam explains, women tend to have larger Q-angles, as they tend to have a greater pelvis-to-femur length ratio.

“It was postulated that a wider Q-angle results in increased angular forces and lateralization forces on the knee, placing the knee at higher risk of injury,” continues Adam. “This lateralization was thought to increase retropatellar pressure between the lateral patellar facet and the lateral femoral condyle.” One study, for example, “reported that a 10% increase in Q-angle resulted in increased patellofemoral joint stress by 45%. Many have postulated that a larger Q-angle, therefore, predisposes one to increased risk of knee injury and patellofemoral tracking problems.”

“Women [tend to be] at increased risk of an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear, due to the structure of their lower limb,” says Lynn. “Women generally have wider hips, which puts the femur at a bigger angle as it meets the tibia at the knee, creating a greater static valgus Q-angle. This means that when moving at high speeds while playing sports, the knee is more likely to collapse inward and put stress on the ACL.”

There have been many studies through the years that suggest this relationship between knee issues and the Q-angle. For example, a study published in the American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation showed that an “abnormal Q-angle” is one of the most common factors that correlates with patellofemoral pain.

The researchers of a 2007 study, which was done to evaluate the relationship between anterior knee pain and the Q-angle, concluded that their results “substantiate the fact that patients with anterior knee pain have larger Q-angles than healthy individuals.” And research published in 2017 backed this finding up, at least among female volleyball players. This study found a positive correlation between a larger Q-angle and knee injuries in elite female volleyball players.

In fact, several studies have shown that females have a greater incidence of knee pain and an average of 3.5 times greater risk of a non-contact ACL injury compared to males.

Are Women Destined to Have Knee Problems?

But is this increase in risk to the knee really all attributable to a larger Q-angle?

“It appears that having a wider Q-angle alone does not necessarily predispose one to increased risk of injuries in the lower extremity, but rather, it’s the dynamic (emphasis added) measure or functional measure of the hip-to-knee angle that is more predictive of injury,” states Adam.

Adam explains that static measures have been less useful in predicting risk of ACL injury—with the exception of the femoral notch width index. “A narrower notch width of the femur has been correlated with higher risk of ACL injury in both genders. The pattern of dynamic valgus of the knee, contralateral pelvic drop, and internal rotation of the femur with single-leg squat or step-down has been demonstrated to predispose one to increased acute injuries of the knee, such as ACL and medial collateral ligament (MCL) tear, as well as chronic injuries, such as patellofemoral pain.”

In fact, one 2010 study found the Q-angle to be a poor independent predictor of lower-extremity injury risk. The researchers determined this, in part, because the Q-angle represents only the frontal plane alignment, and most injuries occur in a combination of the frontal and transverse planes. Another study concluded that the Q-angle presented no relationship with pain intensity or functional capacity in the patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome.

So how can studies come to such opposing conclusions? The answer may at least partially lie in the multiple factors in a woman’s body that can contribute to joint breakdown and injuries. In other words, it’s probably not just one factor that increases a woman’s risk for knee injury, but rather several of them combined.

For example, research published in the Journal of Orthopedics offered a rundown of possible reasons females may be at greater risk of ACL injury compared to males, including hormones, anatomical differences, neuromuscular differences and core stability.

Another study, which was conducted at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, suggested that women who take the birth control pill may be less likely to suffer serious knee injuries. The researchers theorized that this was due to the birth control lowering and stabilizing the levels of estrogen in the women’s bodies.

How Can You, the Health and Exercise Professional, Help?

Regardless of the reasons why your female clients may be at greater risk of knee injuries, you can still help them prevent injury, both acute and chronic.

“Neuromuscular ‘prehab’ programs work to correct [inefficient] movement patterns and have been very successful in decreasing risk of ACL and [other] knee injuries,” says Adam. “The exercises focus on improving neuromuscular control of the hip and trunk with single-leg activities, as well as strengthening of the hamstrings, hip abductors and hip external rotators.”

“We have many big muscles in our hip designed to prevent the knee from collapsing in and controlling the dynamic Q-angle of the knee during movement,” explains Lynn. “[Everyone], but especially women, needs to focus on training this musculature appropriately so that they can dynamically control the movement of their knees and keep them healthy.”

Lynn adds that exercises that strengthen the larger external rotator muscles of the hip—the gluteus maximus and posterior gluteus medius—should be included in a knee prehab program. “One exercise that targets these two main muscles and addresses a lot of common inefficient movement patterns is the single-leg Romanian deadlift (RDL) with reactive neuromuscular training.”

Single-leg Romanian deadlift (RDL)

To perform this exercise, place a band around your client’s stance side leg to pull it into valgus while doing an RDL. The client, in turn, provides opposing force away from the pull. “This activates the appropriate musculature to prevent the knee from going into that valgus position that we know is associated with various pathologies.”

If this exercise is too difficult, have your client place her hand against a wall or hold onto a chair to help with balance so she can focus on proper technique.

“Avoid open-chain weighted exercises, like leg extensions,” advises Adam. “These place significant stress on the patellofemoral joint and are generally not well-tolerated. Closed kinetic chain exercises are more functional and are safer. I recommend squats or leg press.”

Adam says that clients with patellofemoral pain or arthritis in the knee should avoid excessive knee flexion and may have to modify squats to about 30 to 40 degrees flexion. “The patella makes contact in the trochlear groove of the femur with further knee flexion, which may elicit patellofemoral-related pain.”

Lynn reminds us that proper technique extends well beyond the gym. “It is extremely important that we monitor our movement quality carefully when exercising in the gym and in all parts of our lives,” he concludes. “If we don’t do this and we let these inefficient movement patterns manifest themselves and build up over time, they can lead to injury and pain. These inefficient patterns then get so engrained that they are difficult to correct and people end up constantly in pain or injured and unable to move.”

Adam cites several neuromuscular prehab programs that you can use with your clients. These include:

FIFA 11+

Jump-Landing Training

Expand Your Knowledge

Corrective Exercise Specialist [Online Training Course]

The BioMechanics Method® is a comprehensive approach to pain relief through structural alignment, sequential corrective exercise and effective client communication. With assessment and exercise techniques that are easy to understand and implement, you’ll be well-equipped to help your clients achieve improved function and pain-free living.

Best Exercises for Great-looking Legs and Pain-free Knees [article]

This article explains the anatomy behind great-looking legs, provides exercises to avoid to help keep knees pain-free, and presents ideal exercises to incorporate into your clients’ fitness programs.

Corrective Exercise for Musculoskeletal Injuries [Online Training Course]

Corrective Exercise for Musculoskeletal Injuries will teach you the basics of working with clients who suffer from common musculoskeletal injuries. You will gain an understanding of these injuries and learn effective strategies to help your clients return to an active lifestyle and regain physical and emotional well-being.

by

by

What is the Q-angle? “The Q-angle is calculated by drawing a line from your hip to your knee, and another line from your knee through your shin,” explains Scott K. Lynn, PhD, associate professor of clinical exercise science at California State University, Fullerton. “This Q-angle can be valgus—knock-kneed—or varus—bowlegged."

What is the Q-angle? “The Q-angle is calculated by drawing a line from your hip to your knee, and another line from your knee through your shin,” explains Scott K. Lynn, PhD, associate professor of clinical exercise science at California State University, Fullerton. “This Q-angle can be valgus—knock-kneed—or varus—bowlegged."