By Wendy Sweet, Ph.D.

Women in their midlife years are the most likely to be “in and out of exercise,” according to the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (Lucke et al., 2010). In other words, they want to exercise, but something is keeping them from sticking with it over the long term.

The women who participated in my research study told a similar story. They wanted to exercise, but workouts were too hard, and their muscles and joints were sore for days. They also expressed dissatisfaction with exercise professionals who believed that healthy aging was dependent upon high-intensity workouts. The following response from Jay, a 54-year-old woman living in New Zealand, was typical:

“You know, I’ve gone through three personal trainers now. Every one of them put me through workouts that exhausted me. They don’t seem to realize that I’m not 20 anymore. I don’t want to go back to the gym. My joints just hurt so much when I do those workouts now.”

Admittedly, touting the benefits of exhausting, high-intensity workouts used to be my mantra, too. In fact, I was one of the first women to bring this “go hard or go home” workout approach to the New Zealand fitness industry in the late 1980s and early 1990s. What we didn’t anticipate, however, was how our feelings about high-intensity training might change when our bodies began to change, particularly during perimenopause and menopause transitions. As I discovered myself, when intense workouts and busy lifestyles intersect with the changing hormonal environment in menopause, cortisol levels increase significantly. Not only does this cause increased inflammation and joint, muscle and myocardial (cardiac) mitochondrial issues, it causes something called “pregnenolone steal,” which leads to increased hot flashes, anxiety and depression. Given these issues, it’s no surprise that midlife women are reported as the highest demographic to be ‘in and out’ of exercise.

Menopause is a hallmark of a woman’s biological aging. However, many women and health and fitness professionals don’t realize exactly what early midlife hormonal changes occur. The World Health Organization’s Healthy Aging Report (2016) defines midlife as half of the average life expectancy of females, which in the United States is 81 years. Thus, midlife for American women begins at 40 (World Bank, 2015). This means that the transition into biological aging, whereby a woman’s ovaries start to lose estrogen receptors and estrogen production diminishes, starts earlier than once believed. This transition is known as perimenopause and for all women, it is the start of changes to their hormonal environment that can affect their health, energy, exercise response, sleep, moods, bone density, cardiac health and, for many, their weight.

As a health and fitness professional who is helping your female clients reach their health and fitness goals, it is essential that you understand menopause and how it affects the exercise response—and, importantly, how exercise affects how women experience menopause. It is important to realize that women who are in their early 50s now may have been active and exercising in a health club environment for much of their adult lives, which means that they may have engrained beliefs about the type, amount and intensity of exercise that they believe burns calories and provides the most benefits. However, in a changing hormonal environment and with interrupted sleep, weight-management strategies that have worked in the past may no longer work during menopause. Although this is partly due to the biological aging of blood vessels, organs, muscles, tendons and ligaments, and, of course, a changing hormonal environment, it may also be due to the increased cortisol and subsequent insulin disruption that results from too much high-intensity exercise. Additionally, increased fat around the abdominal and diaphragmatic regions is another indicator of inflammation, which contributes to metabolic syndrome, heart disease and, for some, type 2 diabetes. All of this helps explain, in part, why heart disease is the number one health risk for women over the age of 50 in the U.S., Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom (National Institute on Aging, 2012; Kowal et al. (2010).

Clearly, understanding the “science of menopause” is important for many reasons, including helping to mitigate cardiac risk for women (American Heart Association, 2013). This article examines how perimenopause and menopause can dramatically alter a woman’s response to exercise and offers effective strategies for designing programs that are both effective and enjoyable for your clients.

The Science of Menopause

Defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the permanent cessation of menstrual periods that occurs naturally or is induced by surgery, the Greek derivative is men (month) and pausis (cessation). The years preceding menopause that encompass the transition from normal menstruation to cessation are termed perimenopause and are characterized by irregular periods, which may last up to five years. Based on the Massachusetts Women’s Health Study, one of the largest studies on midlife women, the average age of menopause, when menstruation stops completely, is 51 years. This hasn’t changed since ancient times.

Postmenopause begins at the time of the final menstrual period, although it is often not recognized until after 12 months of a woman’s periods ceasing. This cessation of menstruation is known medically as the climacteric, the end of a woman’s reproductive potential. With the huge decrease in estrogen levels that occurs at this time, it is no wonder that hormonal changes cause havoc with the endocrine (hormonal), psychological and somatic (bodily) systems. More importantly, women who don’t manage the menopause transition through symptom and/or weight management, may spiral into negative health changes as they age (Lucke et al., 2010; Church et al. 2009).

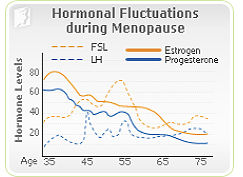

Given that the production of the primary reproductive hormones occurs in the hypothalamus and pituitary gland in the brain, menopause symptoms are, arguably, more about the brain than the ovaries. The human endocrine system works as a negative-feedback loop (i.e., an increase or decrease in a single hormone’s production has an influence over other hormone production in the body). That means when estrogen and progesterone production decreases, the amount of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) released from the pituitary gland changes, too (Figure 1).

Figure 1

FSH is a powerful hormone that controls estrogen production in the ovaries. In the normal menstrual cycle of younger women, another hormone called luteinizing hormone (LH) works in tandem with FSH in estrogen-producing ovulation. However, as perimenopause approaches, the aging ovaries become less responsive to FSH. As such, the amount of FSH rises in the pituitary gland and increases 10 to 20-fold as more and more FSH is released by the pituitary gland to “bribe” the ovaries into responding. LH is cleared from the blood faster, which means that high levels of FSH are what causes havoc on menopausal symptoms during this time. For some women, this can go on for years. As a woman hits her 50s, fewer and fewer follicles respond to the FSH. This can result in symptom chaos for women, both physically and psychologically.

The hormone progesterone, which is the hormone of pregnancy, also is implicated in the hormonal changes caused by low estrogen production. During perimenopause, progesterone levels fluctuate and decline, but this decline can happen more rapidly, particularly when stress and inflammation in the body builds up. So, when women aren’t sleeping and have other stress in their lives, high-intensity exercise programs can propel women into a sharper-than-normal decrease in progesterone levels. When cortisol levels stay high both day and night, it “steals” progesterone from the adrenal gland pathway. This means that progesterone is not available for its usual role, which is to maintain a calm, happy and clear mind. Mood swings, anxiety and depression may all become worse and, for many women, body fat levels increase.

Common Symptoms in Perimenopause

Hot Flashes and Night Sweats

Hot flashes (known as hot flushes in some parts of the world) are clinically defined as instability of the vasomotor system (blood vessel control). The vasomotor system is driven by the adrenal glands through the sympathetic nervous system, which also controls blood pressure and blood vessel dilation.

Hot flashes and night sweats are the hallmark of menopause for many women. Reddening of the face, a sensation of heat and, in some women, profuse sweating drive many to despair. Because these symptoms commonly occur at night, hot flashes are a primary cause of insomnia. Decreased estrogen production, increased feelings of stress and hyperglycemia (high levels of blood glucose) all influence hot flash frequency and severity, as does high levels of vigorous exercise. This is not a surprise, given the adrenal system’s influence on other hormones such as those produced by the thyroid, pancreas and pituitary gland. These hormones control a wide range of body functions, including temperature, blood pressure, metabolism and blood sugar.

The hot flash is the end result of vasodilation, which is how the body is trying to cool down. When hot flashes become intolerable, many women go on hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to reduce their symptoms, but evidence from the Women’s Health Initiative Study (2001) linking long-term use to breast cancer, has resulted in the use of HRT becoming somewhat controversial.

Insomnia

Wakeful nights in perimenopause are often an overlooked symptom of menopause, because women often don’t associate this symptom with their menopause changes. But low estrogen also affects melatonin, the “go-to-sleep” hormone. This sleep hormone is also disrupted by high cortisol levels as well as increased insulin production, because these hormones also affect pineal gland production of melatonin. When melatonin levels remain low, sleep is interrupted and light, so women wake up throughout the night and find it difficult to get back to sleep. When this happens consistently it becomes routine, but lack of sleep increases a woman’s risk for developing heart disease later on. As a health and fitness professional, you must be aware of your perimenopausal and menopausal clients’ sleep patterns, especially for those who are performing vigorous activity or resistance training. When women aren’t sleeping, the restorative hormones—growth hormone and DHEA—are not produced overnight to restore immune system recovery.

Wakeful nights in perimenopause are often an overlooked symptom of menopause, because women often don’t associate this symptom with their menopause changes. But low estrogen also affects melatonin, the “go-to-sleep” hormone. This sleep hormone is also disrupted by high cortisol levels as well as increased insulin production, because these hormones also affect pineal gland production of melatonin. When melatonin levels remain low, sleep is interrupted and light, so women wake up throughout the night and find it difficult to get back to sleep. When this happens consistently it becomes routine, but lack of sleep increases a woman’s risk for developing heart disease later on. As a health and fitness professional, you must be aware of your perimenopausal and menopausal clients’ sleep patterns, especially for those who are performing vigorous activity or resistance training. When women aren’t sleeping, the restorative hormones—growth hormone and DHEA—are not produced overnight to restore immune system recovery.

Estrogen Dominance and Insulin Sensitivity

How many women do you know who continue to put on weight in their midlife years, despite being on a good eating regime and exercising daily? Insulin sensitivity is known to worsen with advancing age and increasing central obesity (diaphragmatic and abdominal obesity), is a common symptom of menopause. High levels of cortisol are the main reason for the development of insulin sensitivity, but so, too, is a condition called estrogen dominance.

Estrogen dominance was relatively unheard of a decade ago, but has become more commonly accepted as a cause of menopausal weight gain. The term refers to the consequence of estrogen storage in fat and liver cells throughout a woman’s life. Hence, because estrogen is stored in these other cells, even in a low-estrogen environment in menopause this stored estrogen plays havoc on progesterone levels, causing them to drop dramatically. This imbalance naturally causes estrogen to dominate the hormonal environment, overshadowing progesterone. With low progesterone, the estrogen is unopposed, which leads to increasing weight gain and insulin resistance from high blood lipids and high levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol—which also happen to be common risk factors for heart disease.

It is important to understand that some women who have exercised regularly in the past and maintained a healthy weight may experience weight gain as they transition through and into menopause. This diaphragmatic weight gain increases their risk of cardiovascular disease three-fold. Women who do not gain weight in this low-estrogen, low progesterone environment, are more likely to experience calcium loss and increased osteoporosis risk (Lucke et al., 2010).

How to Help Your Menopausal Clients Make Sense of Exercise

As a health and fitness professional who helps your clients adopt healthy lifestyle practices, you are in a unique position to support midlife women make positive lifestyle behaviors that align with healthy-aging ideals (Sweet, 2008). Here are five effective strategies you can use to support your menopausal clients in ways that may make a difference to how they feel and how they stay healthy during this phase of life:

- Empathize and inquire. If your client says she is tired, she is. You can’t train a tired client effectively. It’s that simple. While your client may not tell you that she is having a hard time sleeping due to hot flushes and night sweats, it’s your job to inquire.

- Change your client’s cardio from HIIT to a lower-intensity modality until she is sleeping well. If your client isn’t sleeping, she cannot recover from high-intensity exercise. Furthermore, in a low-estrogen environment, her joints and muscles won’t recover well either. Low-t-moderate aerobic exercise has been shown to reduce blood pressure, which will be higher than normal if she is experiencing hot flashes and poor sleep patterns (Earnest et al., 2013). While HIIT is effective in promoting metabolic fat loss, your menopausal client may have low levels of iron, calcium, magnesium and/or vitamin D, poor thyroid function and high cortisol. These are all indicative of adrenal fatigue and recovery from HIIT will be insufficient.

- Remember that too much exercise is harmful as women age. How much exercise is enough? With heart disease on the rise in postmenopausal women, this question is particularly pertinent. To date, only two studies are believed to have answered this question: (1) the Dose-Response to Exercise in Post-menopausal Women’ (DREW) Trial (Earnest et al., 2013) and (2) the Australian Longitudinal Women’s Health Study (Lucke, J. et al., 2010). These studies are the largest exercise interventions to date on postmenopausal women, and both have concluded that both age and volume of training play a significant role in cardiac fitness and reduced blood pressure changes for women. Furthermore, study outcomes have supported national guidelines that advocate the accumulation of at least 30 minutes a day of moderate-intensity physical activity on at least five days per week (150 minutes per week) (American Heart Association, 2007). However, the most striking finding of the DREW study was that even a lower amount of activity (i.e., 72 minutes per week) was associated with a significant improvement in fitness for women in the 55-59 year age group. Both studies indicate an association between physical activity and decreased risk for developing a variety of cancers, diabetes and obesity, and preventing cardiovascular disease with physical activity participation up to three to five hours per week, with diminishing returns at higher levels of activity (Kyu, et al., 2016; Woodward, et al., 2015; Pettee, et al., 2008).

- Recommend functional strength exercises. Again, if your client isn’t sleeping and because she is aging, she doesn’t have enough growth hormone or testosterone available to grow muscle. Over time, this results in sarcopenia (muscle wasting). Sleep is absolutely crucial in recovering from resistance training and preventing sarcopenia, so to help your midlife female clients maintain strength, use exercises that incorporate deep-breathing strategies, such as yoga and Pilates, rather than exhausting weight training with heavy loads.

- Read up on hormone therapies and side effects. A wide range of information is available on supplements for increasing isoflavones and other phytoestrogens to reduce hot flashes. These are not recommended, however, for overweight women who are estrogen dominant. Although several studies of soy extracts suggest that they may have some mitigating effect on hot flashes in women who are not overweight, it is not recommended for women who are overweight to consume soy-based products that contain estrogens.

There is no question that the benefits of being physically active as women age are both proven and well-known (Beard et al, 2015). However, because there is little information about exercise for women during menopause, exercise programming is often approached as a “one-size-fits-all-across-the-lifespan” endeavor. It is evident from reviewing and critiquing the literature that women in perimenopause and menopause are not often the subjects of exercise-related research.

It is important to realize that the women who are in their 50s today were the among first groups of women to embrace the fitness industry in the 1980s (Hentges, 2014). The gym is a familiar space for many women to work out and spend time, but we need to do a better job of adequately supporting both their age and stage of life by creating exercise programs that address their unique needs.

References

American Heart Association (2013). Guide for improving cardiovascular health at the community level: A scientific statement for public health practitioners, healthcare providers and health policy makers. Circulation, 127, 1-47.

American Heart Association (2007). Physical activity and public health. Updated recommendations for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation, 116, 9, 1081-1093.

Beard, J. et al. (2016). The World report on ageing and health: A policy framework for healthy ageing. The Lancet, 387, 10033, 2145-2154.

Brown, W. et al. (2009). Life events and changing physical activity patterns in women at different life stages. Annals of Behavioural Medicine, 37, 294-305.

Church, T. et al. (2009). Changes in weight, waist circumference and compensatory responses with different doses of exercise among sedentary, overweight postmenopausal women. PLoS ONE, 4, 2, E4515.

Earnest, C. et al. (2013). Dose effect of cardiorespiratory exercise on metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal women. The American Journal of Cardiology, 111, 12, 1805-1811.

Hentges, S. (2014). Women and Fitness in American Culture. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland and Company Inc.

Kowal, P. et al. (2012). Data resource profile: The World Health Organization study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE). International Journal of Epidemiology, 41, 6, 1639-1649.

Kyu, H. et al. (2016). Physical activity and risk of breast cancer, colon cancer, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and ischemic stroke events: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. British Medical Journal (Online), 354.

Lucke, J. et al. (2010). Health across generations: Findings from the Australian longitudinal study on women’s health. Biological Research for Nursing, 12, 2, 162-170.

National Institute on Aging (2012). Global Health and Aging.

Pettee, K. et al. (2008). A lifestyle approach for primary cardiovascular disease prevention in perimenopausal to early postmenopausal women. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 2, 5, 421-435.

Sweet, W. (2008). Personal Trainers: Motivating and moderating client exercise behaviour (unpublished Master’s thesis). University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand.

Woodward, M. et al. (2015). The exercise prescription for enhancing overall health of midlife and older women. Maturitas, 82, 1, 65-71

World Bank (2015). Population Data: United States.

World Health Organization (2009). Women and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

World Health Organization, (2015). World report on Ageing and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

by

by

Wakeful nights in perimenopause are often an overlooked symptom of menopause, because women often don’t associate this symptom with their menopause changes. But low estrogen also affects melatonin, the “go-to-sleep” hormone. This sleep hormone is also disrupted by high cortisol levels as well as increased insulin production, because these hormones also affect pineal gland production of melatonin. When melatonin levels remain low, sleep is interrupted and light, so women wake up throughout the night and find it difficult to get back to sleep. When this happens consistently it becomes routine, but lack of sleep increases a woman’s risk for developing heart disease later on. As a health and fitness professional, you must be aware of your perimenopausal and menopausal clients’ sleep patterns, especially for those who are performing vigorous activity or resistance training. When women aren’t sleeping, the restorative hormones—growth hormone and DHEA—are not produced overnight to restore immune system recovery.

Wakeful nights in perimenopause are often an overlooked symptom of menopause, because women often don’t associate this symptom with their menopause changes. But low estrogen also affects melatonin, the “go-to-sleep” hormone. This sleep hormone is also disrupted by high cortisol levels as well as increased insulin production, because these hormones also affect pineal gland production of melatonin. When melatonin levels remain low, sleep is interrupted and light, so women wake up throughout the night and find it difficult to get back to sleep. When this happens consistently it becomes routine, but lack of sleep increases a woman’s risk for developing heart disease later on. As a health and fitness professional, you must be aware of your perimenopausal and menopausal clients’ sleep patterns, especially for those who are performing vigorous activity or resistance training. When women aren’t sleeping, the restorative hormones—growth hormone and DHEA—are not produced overnight to restore immune system recovery.